Giovanni Arrighi, Terence K Hopkins, Immanuel Wallerstein, Anti-Systemic Movements, (London: Verso, 1989).

Thomas Piketty, Capital and Ideology (Cambridge and London: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2020).

M. K. Gandhi, Unto this Last: A Paraphrase (Ahmedabad: Navajivan Trust, 1951).

Timothy Lenton and Bruno Latour, “Gaia 2.0: Could humans add some level of self-awareness to Earth’s self-regulation?” Science 361, no. 6407 (2018).

Dipesh Chakrabarty, “The Climate of History: Four Theses,” Critical Inquiry 35 (2009).

IPCC, Special Report on Climate Change and Land (2019).

Timothy Lenton et al., “Tipping elements in the Earth’s climate system,” PNAS 105, no. 6 (February 12, 2008).

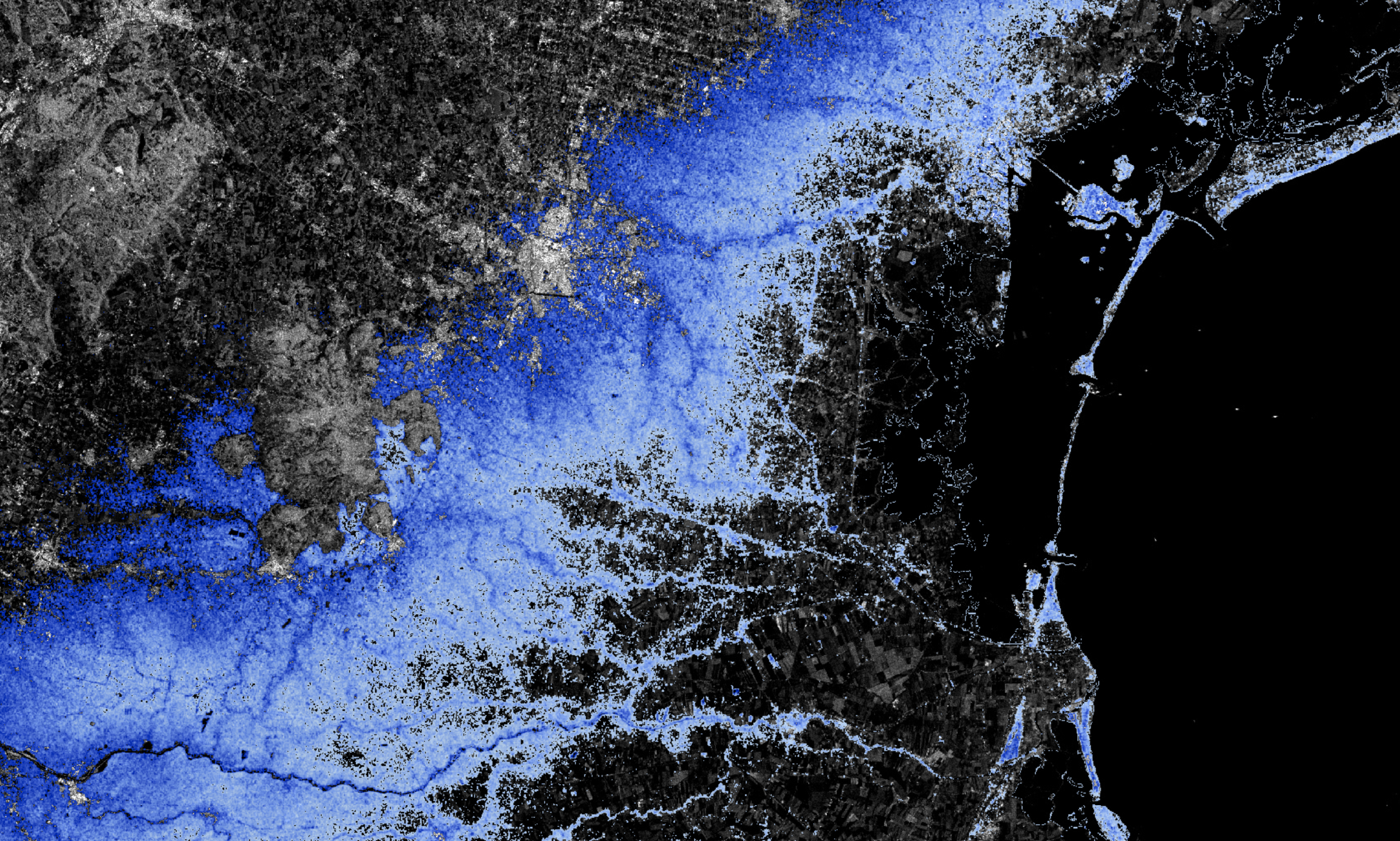

Benjamin H. Strauss, Scott Kulp, and Anders Levermann, Mapping Choices: Carbon, Climate, and Rising Seas, Our Global Legacy (Climate Central, 2015).

IPCC, Special Report; Strauss et al., Mapping Choices.

United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) Paris Agreement, 2015.

IPCC, Special Report on the Ocean and Cryopshere in a Changing Climate (2019).

Franco Farinelli, L’Invenzione della Terra (Palermo: Sellerio editore, 2016).

Davor Vidas, “The Anthropocene and the international law of the sea,” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A, March 13, 2011.

Frederic Jameson, “Time and the Sea,” London Review of Books 42, no. 8 (April 16, 2020).

Stefano Harney and Fred Moten, The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning and Black Study (Wivenhoe, New York, and Port Watson: Minor Compositions, 2013).

George Smith, Chaldean Accounts of Genesis (New York: Scribner, Armstrong & Co., 1876).

Joshua J. Mark, “Enuma Elish—The Babylonian Epic of Creation,” Ancient History Encyclopedia, May 4, 2018, ➝.

D. E. Smith, S. Harrison, C. R. Firth, J. T. Jordan, “The early Holocene sea level rise,” Quaternary Science Reviews 30, no. 15–16 (July 2011): 1846–1860.

Takuro Kobashia, Jeffrey P. Severinghaus, Edward J. Brook, Jean-MarcBarnola, and Alexi M. Gracheva “Precise timing and characterization of abrupt climate change 8,200 years ago from air trapped in polar ice,” Quaternary Science Reviews 26, no. 9–10 (May 2007): 1212–1222.

Ibid.

Jan Zalasiewicz, Colin N. Waters, Mark Williams, and Colin Summerhayes eds., The Anthropocene as a Geological Time Unit: A Guide to the Scientific Evidence and Current Debate (Cambridge University Press, 2019).

James W. McClelland, Robert Max Holmes, Kenneth H. Dunton, R. W. Macdonald, “The Arctic Ocean Estuary,” Estuaries and Coasts 35, no. 2 (2011): 353–368.

Peter Haff, “Humans and Technology in the Anthropocene: Six Rules,” The Anthropocene Review 1, no. 2 (2014): 126–136.

International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA), Global Energy Assessment (2012).

Jan Zalasiewicz, Mark Williams, Colin N. Waters, et al., “Scale and Diversity of the Physical Technosphere: A Geological Perspective,” The Anthropocene Review 4, no. 1 (November 2016): 9–22.

Bruno Latour, An Inquiry into Modes of Existence (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2018).

Fernand Braudel, Civilization and Capitalism: 15th–18th Century, Volume III (London: Collins, 1984).

Elinor Ostrom, Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990).

CNR-ISMAR, “Eccezionale Acqua Alta a Venezia,” September 1, 2019, ➝.

Multiplicity (Stefano Boeri, Maddalena Bregani, Francisca Insulza, Francesco Jodice, Giovanni La Varra, John Palmesino), “ID—A Journey Through a Solid Sea,” documenta 11, Kassel, 2002.

See the forthcoming contributions by Anne McClintock and Jan Zalasiewicz and Mark Williams in this series.

Gilles Deleuze, Bergsonism, trans. Hugh Tomlinson and Barbara Habberjam (New York: Zone Books, 1988).

J. E. Lovelock, R. J. Maggs, and R. J. Wade, “Halogenated Hydrocarbons in and over the Atlantic,” Nature 241 (1973): 194–196.

See the forthcoming contribution by Jeremy Jackson in this series.

Emanuele Coccia, Sensible Life: A Micro-Ontology of the Image (Fordham University Press, 2016).

Samuel Beckett, Our Exagmination Round His Factification for Incamination of Work in Progress: James Joyce/Finnegans wake, a symposium (New York: New Directions Publishing, 1972).

Oceans in Transformation is a collaboration between TBA21–Academy and e-flux Architecture within the context of the eponymous exhibition at Ocean Space in Venice by Territorial Agency and its manifestation on Ocean Archive.