William H. McNeill, Plagues and Peoples (New York ; London: Anchor Books, 1998), 80.

Nicholas B. King, “The Scale Politics of Emerging Diseases,” Osiris 19 (2004): 64.

Jonathan A. Patz et al., “Unhealthy Landscapes: Policy Recommendations on Land Use Change and Infectious Disease Emergence,” Environmental Health Perspectives 112, no. 10 (2004): 1092–98; Kate E. Jones et al., “Global Trends in Emerging Infectious Diseases,” Nature 451, no. 7181 (2008): 990–93; Stephen S. Morse et al., “Prediction and Prevention of the next Pandemic Zoonosis,” The Lancet 380, no. 9857 (2012): 1956–65.

World Health Organization, 2017 data, ➝.

Jessica M. C. Pearce-Duvet, “The Origin of Human Pathogens: Evaluating the Role of Agriculture and Domestic Animals in the Evolution of Human Disease,” Biological Reviews 81, no. 03 (2006): 369; Nathan D. Wolfe, Claire Panosian Dunavan, and Jared Diamond, “Origins of Major Human Infectious Diseases,” Nature 447, no. 7142 (2007): 279–83.

Dorothy Porter, Health, Civilization and the State: A History of Public Health from Ancient to Modern Times (London: Routledge, 2006), 40–43.

Michel Foucault, Security, Territory, Population: Lectures at the Collège de France, 1977–1978 (New York: Picador, 2007), 4–23; Porter, Health, Civilization and the State, 142.

Jürgen Osterhammel, The Transformation of the World: A Global History of the Nineteenth Century (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2014), 176–177.

Beatriz Colomina and Mark Wigley, Are We Human? Notes on an Archaeology of Design (Zürich: Lars Müller Publishers, 2016), 110–116.

See among others Susan Sontag, Illness as Metaphor and AIDS and Its Metaphors (London: Penguin, 2002), 102–122, 146–156.

David Arnold, “The Place of ‘the Tropics’ in Western Medical Ideas since 1750,” Tropical Medicine & International Health 2, no. 4 (1997): 303–13.

Sonia Shah, Pandemic (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2016), 19.

There are two strains of the virus, HIV-1 and HIV-2. HIV-1 derives from a chimpanzee virus, and can be further divided into four subgroups: M (which is the one responsible for the global pandemic), N, O, and P. HIV-2 derives from a virus of the sooty mangabey, and is confined to West Africa. The fact that all subgroups have been dated to the same period gives further credit to the hypothesis of colonialism having played a decisive role in the emergence of the human virus. Throughout the text I will refer to HIV-1M.

Michael Worobey et al., “Direct Evidence of Extensive Diversity of HIV-1 in Kinshasa by 1960,” Nature 455, no. 7213 (2008): 661–64.

The location could be established with a high degree of certainty because only in southeastern Cameroon did wild chimpanzees test positive for SIV. See Brandon F. Keele et al., “Chimpanzee Reservoirs of Pandemic and Nonpandemic HIV-1,” Science 313, no. 5786 (2006): 523–26. See also Paul M. Sharp and Beatrice H. Hahn, “The Evolution of HIV-1 and the Origin of AIDS,” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences 365, no. 1552 (2010): 2487–94.

Nuno R. Faria et al., “The Early Spread and Epidemic Ignition of HIV-1 in Human Populations,” Science 346, no. 6205 (2014): 56–61.

João D. Sousa et al., “High GUD Incidence in the Early 20th Century Created a Particularly Permissive Time Window for the Origin and Initial Spread of Epidemic HIV Strains,” PLoS ONE 5, no. 4 (2010): e9936; João D. Sousa et al., “Enhanced Heterosexual Transmission Hypothesis for the Origin of Pandemic HIV-1,” Viruses 4, no. 12 (2012): 1950–83. João D. Sousa, Viktor Müller, and Anne-Mieke Vandamme. “The Epidemic Emergence of HIV: What Novel Enabling Factors Were Involved?” Future Virology 12, 11 (2017).

David Van Reybrouck, Congo: The Epic History of a People (New York: Ecco, 2015), 53.

Aldwin Roes, “Towards a History of Mass Violence in the Etat Indépendant Du Congo, 1885–1908,” South African Historical Journal 62, no. 4 (2010): 639, 645.

Tamara Giles-Vernick, Cutting the Vines of the Past: Environmental Histories of the Central African Rain Forest (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 2002), 126; Van Reybrouck, Congo, 94.

Sousa et al., “Enhanced Heterosexual Transmission Hypothesis,” 1955.

For an eyewitness account see André Gide, Voyage au Congo, suivi du Retour du Tchad (Paris, Gallimard, 1929); more recently, Catherine Coquery-Vidrovitch, “The Upper-Sangha in the Time of the Concession Companies,” Resource Use in the Tri-National Sangha River Region of Equatorial Africa, Bulletin Series, Yale School of Forestry and Environmental Studies, 102 (1998): 72–84.

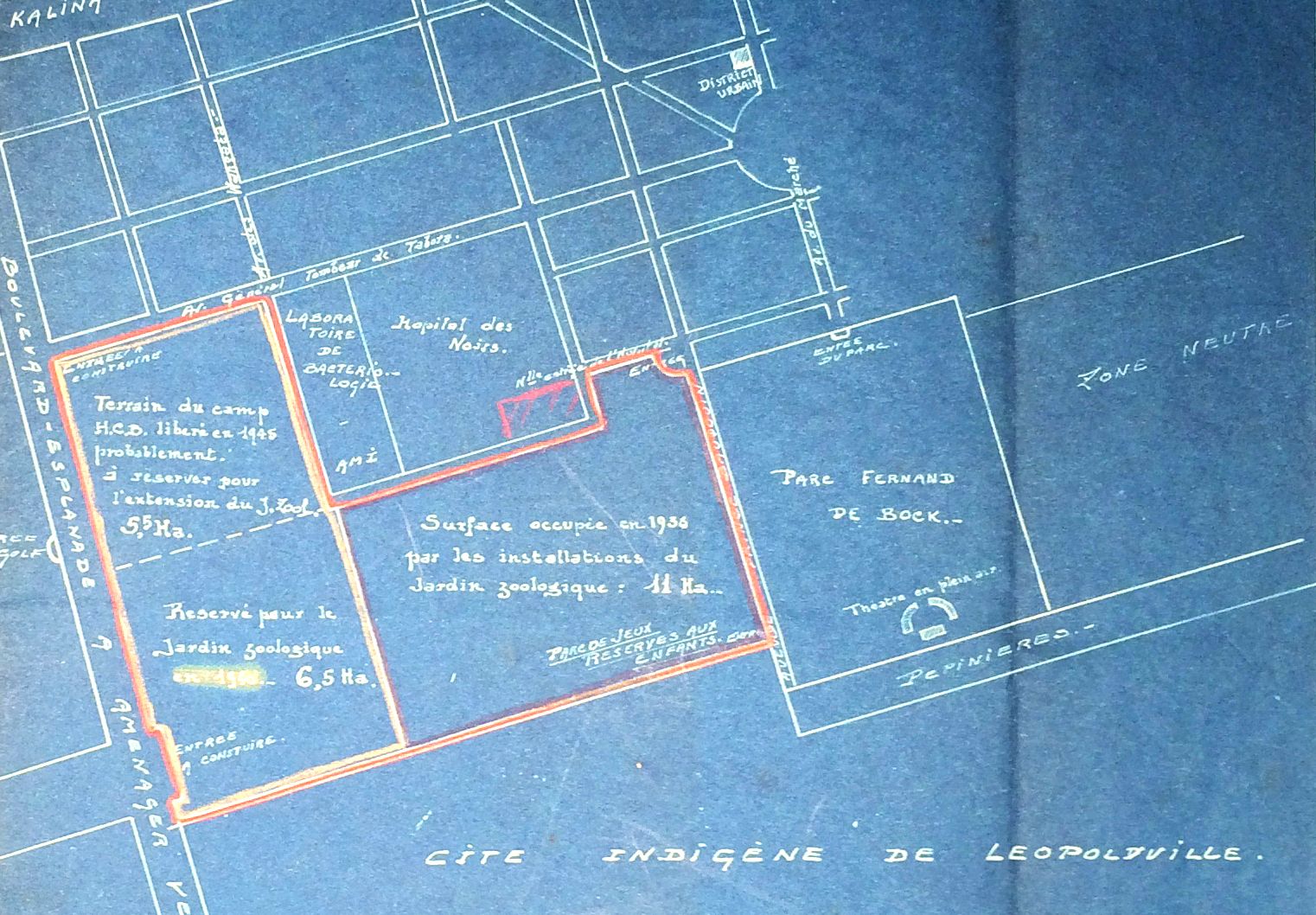

Michel Lusamba Kibayu, “La typologie des quartiers dans l’histoire du développement de Léopoldville-Kinshasa en République Démocratique du Congo,” Notes de recherche, Institut d’études du développement (Louvain-la-Neuve: UCL, 2008), 9–17.

Amandine Lauro, Coloniaux, ménagères et prostituées au Congo belge (1885-1930) (Lovervale: Éditions Labor, 2005).

Bernard Toulier, Johan Lagae, and Marc Gemoets, Kinshasa: architecture et paysage urbains (Paris: Somogy, 2010), 16.

Luce Beeckmans, “French Planning in a Former Colony: A Critical Analysis of the French Urban Planning Missions in Post-Independence Kinshasa,” OASE, no. 82 (2010): 57.

Philip D. Curtin, “Medical Knowledge and Urban Planning in Tropical Africa,” The American Historical Review 90, no. 3 (1985): 613.

Zeynep Çelik, “Le Corbusier, Orientalism, Colonialism,” Assemblage, no. 17 (1992): 68–71.

Alexandre Cabral, Histórias Do Zaire (Lisboa: Orion, 1956), 45; Conversation of the author with João Sousa, Leuven, 18 January 2017.

This essay is part of the long-term project Terra Infecta, which investigates infectious diseases in relation to architecture and urban expansion; it is supported by Het Nieuwe Instituut and the Graham Foundation.

Positions is an initiative of e-flux Architecture.