Charles Jencks, in a debate held at Columbia University on October 26th, 2005.

The first two Chicago Biennials, UCLA, and discourses around practices in the Belgian and Italian scenes can be cited here as representative examples.

See Charles Jencks, The Iconic Building (New York: Rizzoli, 2005).

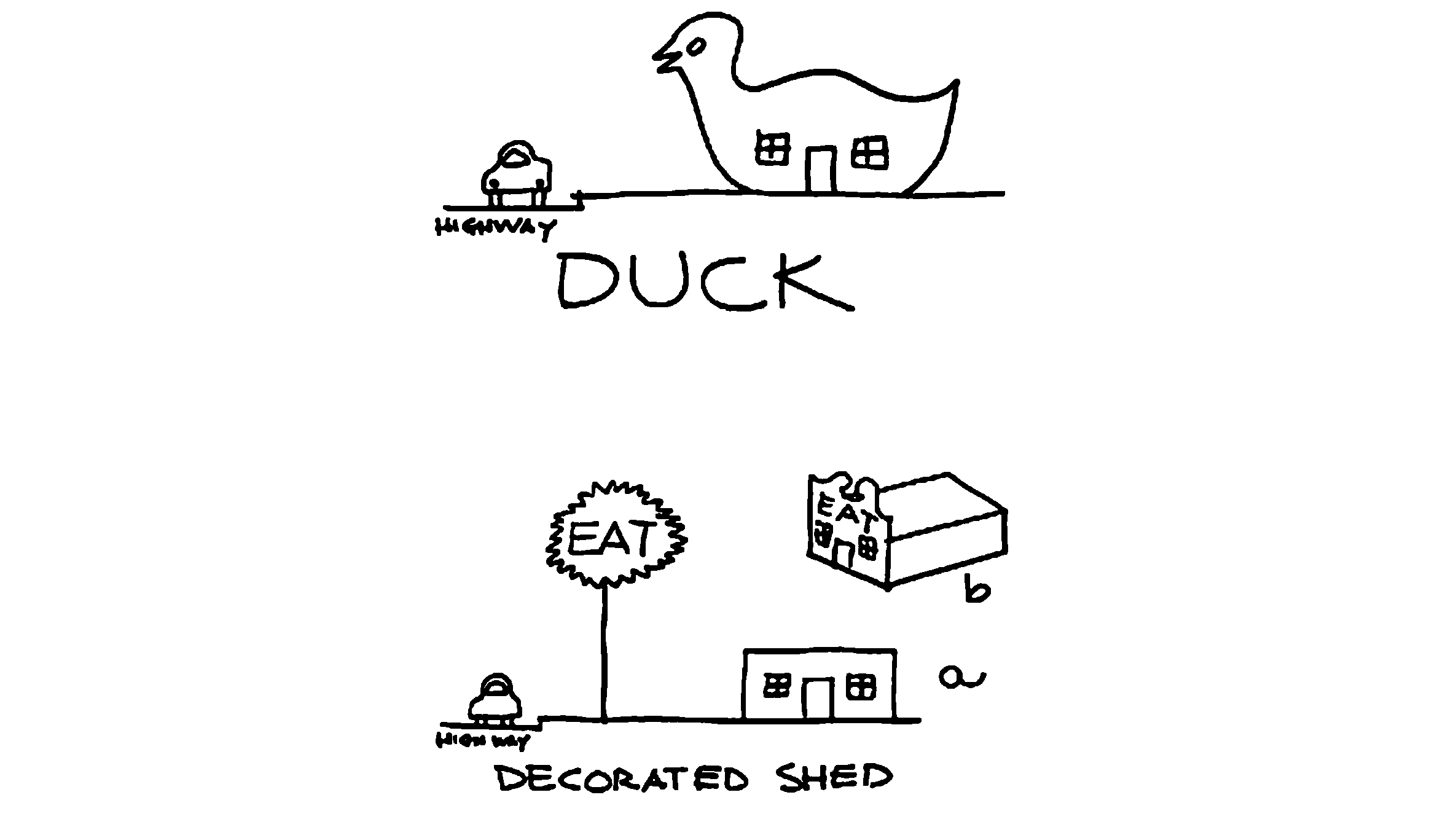

Robert Venturi, Denise Scott Brown, and Steven Izenour, Learning from Las Vegas: The Forgotten Symbolism of Architectural Form (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1977), 87.

The phrase “representational character,” as Sylvia Lavin pointed out, may be made assimilable to Kevin Lynch’s “imageability” and Charles Jencks’s “iconicity.” See Sylvia Lavin, “Practice Makes Perfect,” Hunch, the Berlage Institute Report 11 (2007), 106.

Venturi, Scott Brown, and Izenour, Learning from Las Vegas, 87.

Ibid.

Ibid., 105, 113.

I am adjusting the definition of the term “imageability” to the case of architecture. The original one alluded to “any physical object,” though it was intended specifically for the city. See Kevin Lynch, The Image of the City (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1960), 9. Also, it is worth comparing my redefinition to Anthony Vidler’s use of the term when alluding to Reyner Banham’s discussion of the concept of “image” in his The New Brutalism piece. See Anthony Vidler, “Toward a Theory of the Architecture Program,” October 106 (Fall 2003), 70.

Due to the significant volume of visitors attracted from outside the Basque region, the museum generated, in as little as two years, as much money as to finance another four Guggenheims. This economic dynamic seduced an overwhelming amount of foreign entrepreneurs that went to the Northern Spanish city to invest, which greatly boosted the fortune of the region. The relevance in the media, however, turned Bilbao’s Guggenheim into something more than just a local success. For a more elaborate discussion on the impact of this building for the city of Bilbao, see Jencks, The Iconic Building.

See Penelope Dean, “By No Means Representation,” Hunch, the Berlage Institute Report 11 (2007): 14–15.

See John McMorrough, “Blowing the Lid Off Paint,” Hunch, the Berlage Institute Report 11 (2007), 64–73.

See Penelope Dean, “Blow-Up,” Hunch, the Berlage Institute Report 11 (2007), 76–83.

Robert Somol, “Green Dots 101,” Hunch, the Berlage Institute Report 11 (2007), 28, 34–35.

Jencks, The Iconic Building, 84, 86. Jencks used Daniel Libeskind’s proposal for the Ground Zero to illustrate this notional construct.

Alejandro Zaera-Polo, “La Ola de Hokusai,” Quaderns d’Arquitectura i Urbanisme 245 (April 2005), 80. My translation and emphasis throughout.

Ibid., 86.

Ibid., 80.

The “castellers” are human towers built traditionally in festivals at many locations within Catalonia (Spain).

Zaera-Polo’s piece, along with two related lectures he had previously delivered at UCLA and Princeton in 2004, prompted some severe criticism. The most penetrating was put forward by Jeff Kipnis, who talked about “literal ways of architectural signification,” “the flirtation of FOA with vulgar symbolism,” and “withered terms {in reference to the use of ‘metaphor’}” when referring to the propositions of the Spanish architect. He added that Zaera-Polo had confused “the two referential possibilities of (every) architectural form,” namely, the pictorial—as the realm of representational effects mimicking a reality from a domain other than architecture—and the significative—as that which, including the symbolic, alludes to the use of formal and architectural conventions that are historically and traditionally charged with the view to conveying agreed associations and interpretations (e.g. the conventions of classical language). See Jeff Kipnis, “Lo Que Aquí Conseguimos Necesitamos Es ¡No Comunicar!,” Quaderns d’Arquitectura i Urbanisme 245 (April 2005), 94–98. My translation. Along the same lines, see Sylvia Lavin, “Conversaciones Acompañadas de Cocktails,” Quaderns d’Arquitectura i Urbanisme 245 (April 2005), 88–92. Kipnis further argued that, in fact, the pictorial, qua traditional effect in sculpture, has no equivalent in architecture, where it can only take place as ornament—that is, in reference to the part, but never to the whole. Here is where I part with him, for this essay, as shall become more apparent further on, contends the possibility of the exact opposite: that ornament may be mobilized in its organizational properties so as to structure the whole of a building. This is precisely the way in which the figural, whether as “pictorial” of “significative,” bears potential for architecture beyond its effects in the realm of the representational—i.e. insofar as it can enter that of spatial articulation. In the same piece, Kipnis posed the question whether it is possible to conceive of a kind of figuration in architecture that escapes representation, in the sense of eluding the significant effect. While I see my argument as the beginning of an answer to this question, I will not elaborate here on how that is the case. Nor will I discuss how such an argument relates to other aspects that Kipnis associates with the non-significant figural, such as the fact that it is supposed to involve architectural traits that are disciplinary specificities in themselves, and the ways in which these, by avoiding imitation, can only be rooted in the figurative history of the discipline of architecture.

The phrase “dispositional thinking” is used here to designate thinking processes in architectural design dealing with questions of three-dimensional spatial disposition. Understanding retrospectively that “The Hokusai Wave” was but a prelude to his subsequent Politics of the Envelope project (begun in 2008) would be another way to show that by the mid-2000s Zaera-Polo was mostly concerned with questions of external envelope. See Alejandro Zaera-Polo, “The Politics of the Envelope: A Political Critique of Materialism,” Volume 17 (Fall 2008), 76–106. The ideas he promoted then ought to be seen as the initial manifestations of the increasing pragmatic valance of his thinking. Being preoccupied with getting his projects realized while trying to maintain a certain experimental quality for them, Zaera-Polo started to focus more and more on questions of communication while progressively giving up on the interior. Exemplary of this shift was FOA’s John Lewis department store in Leicester (2000–2008), a box-like construction whose skin is a glass façade printed with embroidery patterns. This building is considerably easier to get built than, say, a Yokohama Terminal, but it is also not nearly as sophisticated an architectural project. Let us recall that the central premise in The Politics of the Envelope was that the architect had largely lost his say in questions of spatial organization, and therefore he should focus on designing and theorizing the envelope alone.

Kenneth Frampton, “Rappel à L’Ordre, the Case for the Tectonic (1990),” in Theorizing a New Agenda for Architecture, an Anthology of Architectural Theory 1965-1995 (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1995), 516–520.

Lavin, “Practice Makes Perfect,” 109.

Elsewhere I have written about one particular species of architecture arising from thinking spatial organization through protocols of representation: the sponge building. See José Aragüez, “Sponge Territory,” Flat Out 2 (Spring 2017), 32–36. This species of building displays a series of features particular to it—such as a certain geometric kernel that generates a specific sequence of spaces—while materializing the general principles laid out above.

For historical examples of ducks and sheds, see Venturi, Scott Brown, and Izenour, Learning from Las Vegas, 104ff.

Alfred Neumann, “Architecture as Ornament,” Zodiac 19 (1969), 90–98.

For a recent elaborate study of the role of space packing in Neumann’s architectural thinking, see Rafi Segal, Space Packed: The Architecture of Alfred Neumann (Zurich: Park Books, 2018).

For an extended definition see Keith Critchlow, “Closepacking,” Zodiac 22 (1972), 172–178.

See Madelon Vriesendorp’s drawings in Jencks, The Iconic Building, 186.

See Aragüez, “Sponge Territory.” The Taichung Opera House is more relevant here than another project by Ito brought up more often when questions of representation are at stake: the TOD’s Omotesando building in Tokyo, completed in 2004. Here a link exists only between the ornamental qualities of the façade (its looking like a tree) and its properties as a load-bearing structure, while the rest of the building is a rather conventional floor-upon-floor articulation. For an insightful take on the decorative character of structural envelopes in contemporary architecture, see Nina Rappaport, “Deep Decoration,” 30/60/90 10 (2006), 95–103.

The qualifier “constructionist” is here used to invoke a recent tendency in theories of critique within the Humanities and Social Sciences whereby the final result of criticism is not simply an oppositional, negative view of the current state of affairs, but rather a set of directives toward the construction of a parallel regime of reality. This regime is conceived as the result of reconfigurations and new assemblies of the constituents of the existing reality within the targeted domain, for instance that of perception, signification, and politics, to mention a few. For a discussion of the possibility of a constructionist criticality in architecture at the intersection with this larger tendency in the Humanities and Social Sciences, see José Aragüez, “On Architecture’s Metacriticality,” in Chris Brisbin and Myra Thiessen, The Routledge Companion to Criticality in Art, Architecture, and Design (Milton Park and New York: Routledge, 2018), 167–178. Two texts essential to the larger trend include Jacques Rancière, The Emancipated Spectator (London: Verso, 2010), and Bruno Latour, “Why Has Critique Run Out of Steam? From Matters of Fact to Matters of Concern,” Critical Inquiry, no. 30 (Winter 2004), 225–248.

Frampton, “Rappel à L’Ordre, the Case for the Tectonic (1990),” 516–20.