Hanna Pitkin. The Concept of Representation. (University of California Press: Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1967) 8.

From Filippo Brunelleschi’s cracked egg for the Duomo in Florence to Rem Koolhaas’ repurposing of a house for a private client into an entry for the Porto Opera, creativity myths in architecture often seem to revolve around the working model as a site of invention and surprise during periods of competition.

This description is based upon the Non-Uniform Rational B-Spline (NURBs) modeling software, Rhinoceros 3d, which was originally developed by Robert McNeel and Associates in 1992 as a plugin for AutoCAD. Since the release of Rhinoceros 1.0 in 1998, this software has become one of the most widely used tools for modeling in professional architecture schools. The feature of automatic drawing capture, or Make2d, has reversed the traditional sequence of design, allowing the architect to produce a model first and then to extract two-dimensional plans and sections as well as perspective and isometric drawings. The term “line-work,” originally used in the context of lithographic printing to describe the concrete labor of working over sections or layers of an image with line-making implements, such as crosshatching, here refers to the solution of a hidden line-removal algorithm.

I have used “total” to refer to forms of architectural representation that aspire towards an exhaustive description of their objects, even if this totality is short lived or never realized. Limit cases of representational totality can be found within the realm of fiction, such as Jorge Luis Borges’ map at the scale of the territory, or Jonathan Swift’s Lagadonian language professors, who, in Gulliver’s Travels, abolish words altogether, decreeing that it would be more expedient for each member of their society to carry, at all times and in large packs, the very things which they would like to refer to. Jorge Luis Borges "On Exactitude in Science." (1946), in Collected Fictions trans. Andrew Hurley (New York: Viking Penguin, 1998), 325. Jonathan Swift, Gulliver’s Travels (Mineola, New York: Dover, (1726) 1996) 137.

G.W.F. Hegel, The Phenomenology of Spirit, trans. A.V. Miller, (New York: Oxford University Press, 1977), 1.

Michel de Certeau, The Practice of Everyday Life, trans. S.F. Rendall (Berkeley, California: University of California Press, 1984), 98-99.

Robin Evans, “Translations from Drawing to Building,” AA Files 12 (1986), 12.

Incomplete in the sense that this analogy rests upon a correspondence between the mechanical nature of architectural documentation, performed through divisions of labor and partial forms of expertise that are themselves indexed in the separation of drawings (and by extension the separation of building components) and a mechanical object that is assembled from discrete parts. To put forward an alternative analogy of expansion or compression between the drawing and building (or to do away with one of these two poles entirely) one would have to rethink fundamentally the routines and procedures of architectural work.

Vittorio Gregotti. “Scale della Rappresentazione,” Casabella 48, 504 (July 1984), 3.

If a drawing is produced beyond a 1:1 scale, the design will usually anticipate a form of construction that requires extreme precision. The full scale could be thought of as a kind of professional threshold in this sense; beyond this level of detail, architecture borders on the material sciences. At a much smaller scale, the architectural drawing reaches another kind of limit as it begins to assume the characteristics of cartography. The 1:4000 site plan may have the quality of a small map, depicting the relationship between a building and the surrounding city or landscape. Beyond this distant scale, the outline of the architectural figure is abstracted into a single locative symbol. The plan becomes a map at the moment when it loses its ability to demarcate space, falling out of correspondence with its larger scale versions.

Bruno Latour. "From RealPolitik To Dingpolitik Or How To Make Things Public." in Making Things Public: Atmospheres Of Democracy, eds. Bruno Latour and Peter Weibel (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2005). Elsewhere, Latour has grouped “engineering drawings” within his category of “inscriptions”- those visible documents that possess the qualities of being mobile, immutable, presentable, readable and combinable with one another. Despite their mundaneness- their presence in everyday routines that are “close to the eye”- inscriptions emerge in Latour’s account as powerful mediators that prompt debate and communication between actors, making what is elsewhere present and what is fictional real within the “optically consistent” space of the page. Bruno Latour, “Drawing Things Together,” in Representation in Scientific Practice, eds. Michael Lynch and Steve Woolgar (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1990), 19–68. While working drawings would seem to serve as ideal nodes within an Actor Network Theory of the production of architecture, ANT’s emphasis on the visible features of objects might overlook the productive absences or ellipses that I have attempted to describe in this paper. For example, Albena Yaneva’s now well-known observational study of modeling practices at the Office for Metropolitan Architecture in 2001 focuses entirely on outwardly apparent debates concerning physical working models in an effort to show how different scales of resolution determine different possibilities for design. Through foregrounding the design meeting as well as more informal, and recordable, conversations between workers, Yaneva misses the non-verbal and virtual interactions that occur within shared files, over email correspondence, and through the protocols of architectural documentation that exist outside of the particular ethnographic histories of each project. Albena Yaneva, "Scaling Up and Down: Extraction Trials in Architectural Design," Social Studies of Science 35, 6 (2005).

A more dramatic example of this kind of saccadic comprehension is presented in the culminating scene of Michelangelo Antonioni’s Blow-Up, in which David Hemmings carries out a forensic pin-up on the back wall of his apartment. Acting on a hunch, Hemmings continues to enlarge a single photograph of a park scene, juxtaposing and cross-referencing each version of the photograph until he is able to piece together the events of a murder. Hemmings looks away from the image between each act of enlargement, shuttling more and more quickly between the impromptu gallery and the darkroom. It is in these periods of transit that the relationship between the multiple scales of the photograph becomes apparent to the photographer, only to be confirmed for the viewer in one final blow-up. Blow-Up. dir. Michelangelo Antonioni. (Italy, UK: Warner Bros. 1966) DVD.

As the philosopher of cognition Elizabeth Camp has described, “Cartographic systems are a little like pictures and a little like sentences. Like pictures, maps represent by exploiting isomorphisms between the physical properties of vehicle and content. But maps abstract away from much of the detail that encumbers pictorial systems. Where pictures are isomorphic to their represented contents along multiple dimensions, maps only exploit an isomorphism of spatial structure- on most maps, distance in the vehicle corresponds, up to a scaling factor, to distance in the world.” Elizabeth Camp. “Thinking with Maps,” Philosophical Perspectives 21:1 (Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2007) 157–158.

Gérard Genette, Narrative Discourse, trans. Jane E. Lewin. (Cornell: Cornell University Press, 1980), 108.

George Barnett Johnston has described the introduction of principles of Scientific Management into the drafting room during this period through a close reading of Architectural Graphic Standards and debates within the journal of the drafting profession, Pencil Points. George Barnett Johnston. “The Division of Architectural Labor,” in George Barnett. Drafting Culture: A Social History Of Architectural Graphic Standards (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2008), 74–85. In the The Portfolio and the Diagram, Hyungmin Pai examines a wider array of architectural artifacts during the interwar period, including drawings, books, journals, manuals, specifications, and contracts in order to track the dissolution of the Beaux Arts system and the rise of a pluralist “discourse of the diagram” within American modernism. Hyungmin Pai, The Portfolio And The Diagram: Architecture, Discourse, And Modernity In America (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2002).

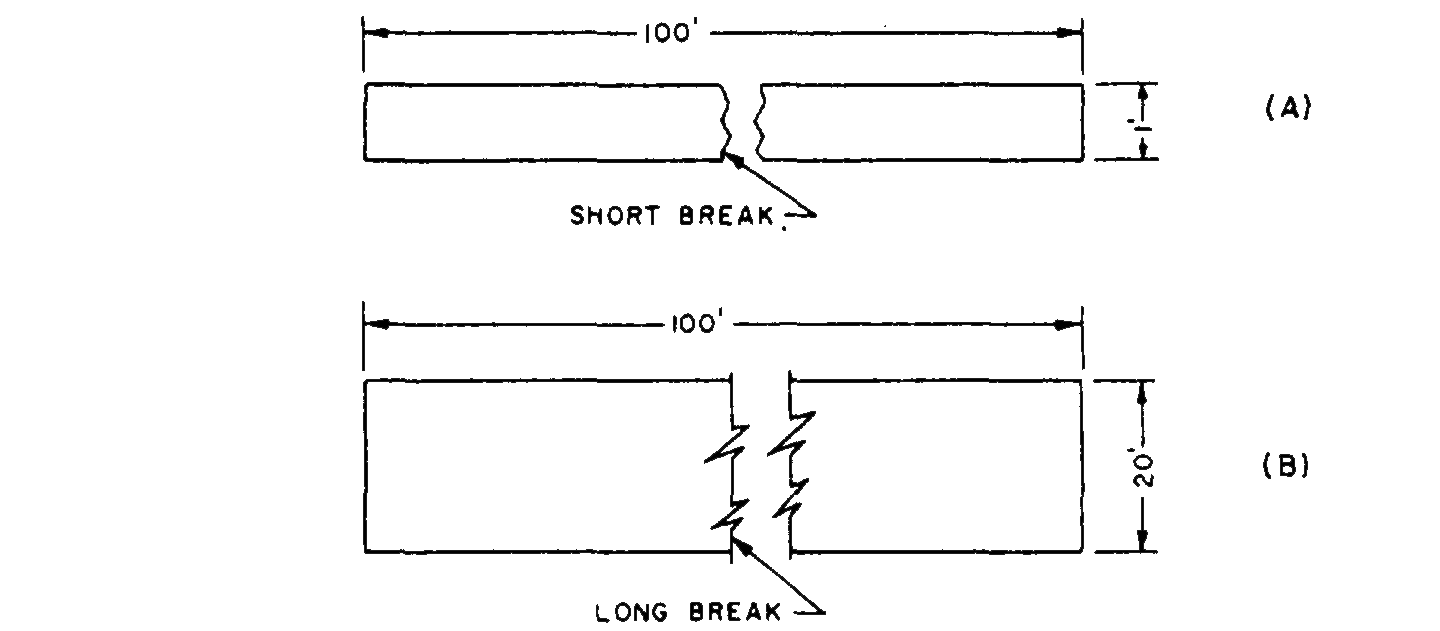

Describing the limit between established and inferred information in communication, Bateson writes: “Any aggregate of events or objects…shall be said to contain ‘redundancy’ or ‘pattern’ if the aggregate can be divided in any way by a ‘slash mark,’ such that an observer perceiving only what is on one side of the slash mark can guess, with better than random success, what is on the other side of the slash mark. We may say that what is on one side of the slash contains information or has meaning about what is on the other side.” While Bateson offers a series of non-graphic examples of this guesswork- the roots of a tree can be inferred from the tree above, the letter “h” or “r” or a vowel is likely to follow the letter “t” in the English language, the actions of the boss yesterday predict the actions today- these kinds of slash marks abound in architectural drawing as well. Gregory Bateson, Steps to an Ecology of Mind (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1972) 130–131.

In the fully saturated page of working details, these represented parts are not merely fragments within a catalog; rather the break line tethers them into a chain of events - their sequence can be tracked around the perimeter of a room, across a façade, or along the length of a passageway. While this type of sequential movement seems to bear some relation to an “architectural promenade”—a hierarchical progression of views that one might experience while moving through a building—it is non-retinal, representing instead a collection of related orthographic vignettes that are visible only in the imaginary and regulated space of the measured drawing.

Works within this genre have recently been collected by Craig Dworkin in his study of post-war conceptual art and literature that is blank, erased, clear, or silent. Craig Dworkin, No Medium (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2013).

Edwin Mather. Wyatt, Blue Print Reading; Interpreting Working Drawings (Milwaukee, WI: Bruce Pub. Co., 1920), 35. Mather’s “serious accidents” can be illustrated through Buster Keaton’s “One Week,” from 1920 and the animated Pink Panther film, “Pink Blueprint” from 1966, which both spoof the protocols of the construction site, and the accidents that inevitably ensue from errors in the drawing. More recently the slapstick genre of “Architecture Fail” images, circulating within online message boards and multipage slideshows reveal numerous examples of overly literal interpretations of drawing conventions. See, for instance, ➝.

Architecture and Representation is a collaboration between Het Nieuwe Instituut, The Berlage, and e-flux Architecture.