Gray Brechin, Imperial San Francisco: Urban Power, Earthly Ruin (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999), 29.

Ibid., 30. Quote cited from Emil Bunje and James C. Kean, Pre-Marshall Gold In California (Sacramento: Historic California Press, 1983; reprint of 1938 edition), 44.

See Pekka Hämäläinen and Samuel Truett, “On Borderlands,” The Journal of American History 98, no. 2 (2011): 338–61. Californios can be described as an ethnically mixed group of settlers that lived for several generations in California and descended from Spanish colonizers, African slaves, and Native Americans. For more information see Ryan Reft, “From Alta California to American Statehood: Race, Change, and the Californio Pico Family,” in East of East: The Making of Greater El Monte, eds. Ryan Reft et al. (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2020), 37–48.

For a thorough accounting of how racist ideas evolved in the United States, see Ibram X. Kendi, Stamped From the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America (New York: Nation Books, 2016).

The state’s 1852 census, conducted to supplement the federal 1850 census, used “color” as a category and assigned individuals to either white, negro, mulatto, and domesticated Indians. Most Native Americans in California and the United States, however, were not included in census reports prior to 1900. For a discussion of how race functioned in the first state and local laws of California, see Shirley Ann Wilson Moore, “‘We Feel the Want of Protection’: The Politics of Law and Race in California, 1848–1878,” in Taming the Elephant: Politics, Government, and Law in Pioneer California, eds. John F. Burns and Richard J. Orsi (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003), , 96–125.

For a full account of the Chinese in San Francisco and the blame and stigma they experienced with regards to disease, see: Susan Craddock, City of Plagues: Disease, Poverty, and Deviance in San Francisco (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2000), 10; Guenter B. Risse, Plague, Fear, and Politics in San Francisco's Chinatown (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012); and Nayan Shah, Contagious Divides: Epidemics and Race in San Francisco's Chinatown (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001).

Mitchel Roth, “Cholera, Community, and Public Health in Gold Rush Sacramento and San Francisco,” Pacific Historical Review 66, no. 4 (November 1997): 527–551.

Ibid., 531. Quote cited from James R. Garniss and Hubert Howe Bancroft, “The Early Days in San Francisco,” 1877, Bancroft Library.

Ibid., 529.

Ibid., 532.

John Morrill Bryan, Robert Mills: America's First Architect (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2001). Mills is best known for his designs in Washington, D.C. including the Washington Monument, the Department of Treasury Headquarters, and the Post Office Headquarters, to name a few. He was the first official architect and engineer of the federal government.

See John Woodworth, First Annual Report of the Supervising Surgeon of the Marine Hospital Service of the United States: For the Year 1872, Containing a Brief Historical Sketch of the Service from the Date of Its Organization in 1798 (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1872), cited in Norman E. Tutorow, “A Tale of Two Hospitals: U.S. Marine Hospital No. 19 and the U.S. Public Health Service Hospital on the Presidio of San Francisco,” California History 75, no. 2 (Summer 1996): 154–169.

“The Marine Hospital: Description of the New Buildings—The Pavilion Plan to be Carried out,” San Francisco Chronicle, May 10, 1874.

Tutorow, “A Tale of Two Hospitals,” 165.

Jeanne Kisacky, Rise of the Modern Hospital: An Architectural History of Health and Healing, 1870–1940 (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2017), 4.

“Five Miles of Wire: For the French Hospital One of the Most Extensive Jobs of the Kind Ever Undertaken Here,” San Francisco Chronicle, July 11, 1894.

“New German Hospital Viewed from Noe Street: It Will Cost Four Hundred Thousand Dollars and Be the Finest Institution of Its Kind in the West,” San Francisco Chronicle, May 1, 1904.

John B. C. Saunders, “Geography and Geopolitics in California Medicine,” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 41 (1967): 293–324, cited in Guenter B. Risse, “Translating Western Modernity: The First Chinese Hospital in America,” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 85, no. 3 (2011): 413–47.

Shah, Contagious Divides, 3–4.

California State Board of Health, First Biennial Report of the State Board of Health of California for the years 1870 and 1871 (Sacramento: D.W. Gelwicks State Printer, 1871).

Ibid., 9.

Ibid., 44–46.

Ibid., 47. Coolie was a term that was originally assigned to unskilled indentured workers from South Asia and China that Britain exported to their colonies—largely following the abolition of slavery in the British Empire.

See Joshua S. Yang, “The anti-Chinese Cubic Air Ordinance,” American Journal of Public Health 99, no. 3 (2009): 440.

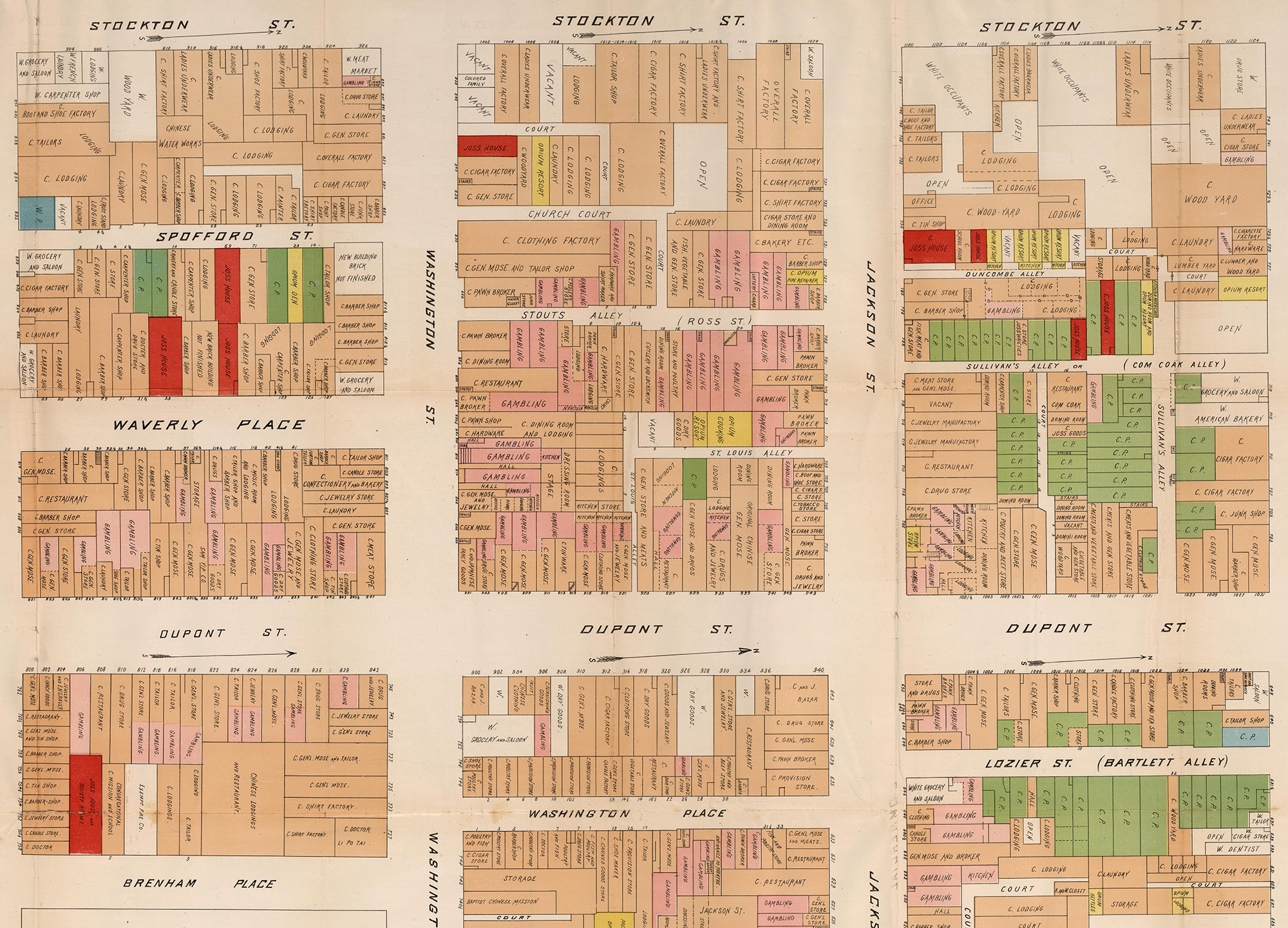

Craddock, City of Plagues, 10.

Ibid., 11. This term is used to describe how geographic spaces, like Chinatown, can be pathologized through the lens of disease and deviance.

Several books and articles have been written on the exclusionary laws that targeted Asian migration to the United States. The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 was the first U.S. law that excluded an entire ethnic group from immigrating to the U.S.

Risse, “Translating Western Modernity.”

Ibid., 413–419.

Philip P. Choy, San Francisco Chinatown: A Guide to Its History & Architecture (San Francisco: City Lights Books, 2012), 44–45.

Shah, Contagious Divides, 152–153.

Sara Anne Hook, “You've got mail: hospital postcards as a reflection of health care in the early twentieth century,” Journal of the Medical Library Association 93, no. 3 (2005): 386–393.

Beatriz Colomina, Privacy and Publicity: Modern Architecture as Mass Media (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1994).

Shah, Contagious Divides, 226.

Yi-Ren Chen, “Chinese Hospital: A Study of San Francisco’s Chinatown Attitudes towards Western Medical Practices at the Turn of the Century,” Herodotus 16 (Spring 2006): 69–83.

“First Chinese Hospital Ready to Open: Chinatown to Celebrate Big Forward Step,” San Francisco Chronicle, March 19, 1925.

“First Chinese Hospital Ready to Open.”

Shah, Contagious Divides, 2.

Ivan Light, “From Vice District to Tourist Attraction: The Moral Career of American Chinatowns, 1880–1940,” Pacific Historical Review 43, no. 3 (1974): 367–94.

Shah, Contagious Divides, 208.

Ibid., 246-247. Racially restrictive covenants date back to the nineteenth century in the United States, but were especially used in the early to mid-twentieth century. They were deemed unconstitutional in 1948 in the Supreme Court ruling Shelly v. Kraemer (1948). See Eli Moore, Nicole Montojo, and Nicole Mauri, Roots, Race, and Place: A History of Racially Exclusionary Housing in the San Francisco Bay Area (Berkeley: Haas Institute for a Fair and Inclusive Society at UC Berkeley, 2019); Richard Rothstein, The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America (New York and London: Liveright Publishing Corporation, 2017).

Ibid., 252–253.

Ching Lin Pang and Jan Rath, “The Force of Regulation in the Land of the Free: The Persistence of Chinatown, Washington D.C. as a Symbolic Ethnic Enclave,” in The Sociology of Entrepreneurship (Research in the Sociology of Organizations 25), eds. Martin Ruef and Michael Lounsbury (Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing Limited, 2007), 191–216.