Edgard Roquette Pinto, “Inaugural Session,” First Brazilian Congress of Eugenics, 12.

Roquette Pinto, “Second Session,” First Brazilian Congress of Eugenics, 16.

Roquette Pinto, “Inaugural Session,” First Brazilian Congress of Eugenics, 12.

Bruno Latour argues that, within hygiene’s ambition for reorganizing society itself, there was “a mixture of urbanism, consumer protection, ecology (as we would say nowadays), defense of the environment, and moralization.” Bruno Latour, The pasteurization of France (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1993), 17–23. See also Fabienne Chevallier, Le Paris moderne: Histoire des politiques d’hygiène, 1855-1898 (Rennes: Presses universitaires de Rennes, 2010).

Jean-Baptiste Pierre Antoine de Monet de Lamarck, Philosophie zoologique, ou Exposition des considérations relatives à l'histoire naturelle des animaux (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011).

Francis Galton, “Eugenics: Its definition, Scope and Aims,” The American Journal of Sociology X, no.1 (1904): 1–25. This definition was first read at London University’s School of Economies, on May 16, 1904.

Beatriz Colomina, in an interview with Anatxy Balbeascoa published in the Spanish newspaper El País, said that “architecture has been studied from every point of view except from the most obvious: the clinical one.” Beatriz Colomina, “Los Arquitectos buscamos Dioses para adorarlos,” El País, April 20, 2009, ➝.

The core of these ideas draws from my book, Eugenics in the Garden: Transatlantic Architecture and the Crafting of Modernity (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2018).

In France, the term “social question” refers to the bourgeoisie’s haunting interrogation of a new form of poverty associated with the advent of industrialization, the crisis of philanthropic reform within the new liberal economy, and the impact of urban growth. At the turn of the twentieth century, the term also captured the fear of change itself, of workers and labor militancy. López-Durán, Eugenics in the Garden, 44.

The sanitary and urban reforms developed during the first decades of the century were not limited to sewage works and avenues’ openings; they also included medical policies that, among other actions, forced the population to be vaccinated for smallpox—a campaign widely rejected. Nicolau Sevcenko, A Revolta da Vacina: Mentes insanas em corpos rebeldes (São Paulo: Scipione, 2003); Jaime Benchimol,”Reforma urbana e revolta da vacina na cidade do Rio de Janeiro,” O Brasil republicano: o tempo do liberalismo excludente – da Proclamação da República à Revolução de 1930, ed. Jorge Ferreira and Lucilia de Almeida Neves Delgado (Rio de Janeiro: Civilização Brasileira, 2003); and Gilberto Hochman, A era do saneamento: As bases da política de saúde pública no Brasil, (São Paulo: Hucitec/Ampocs, 1998).

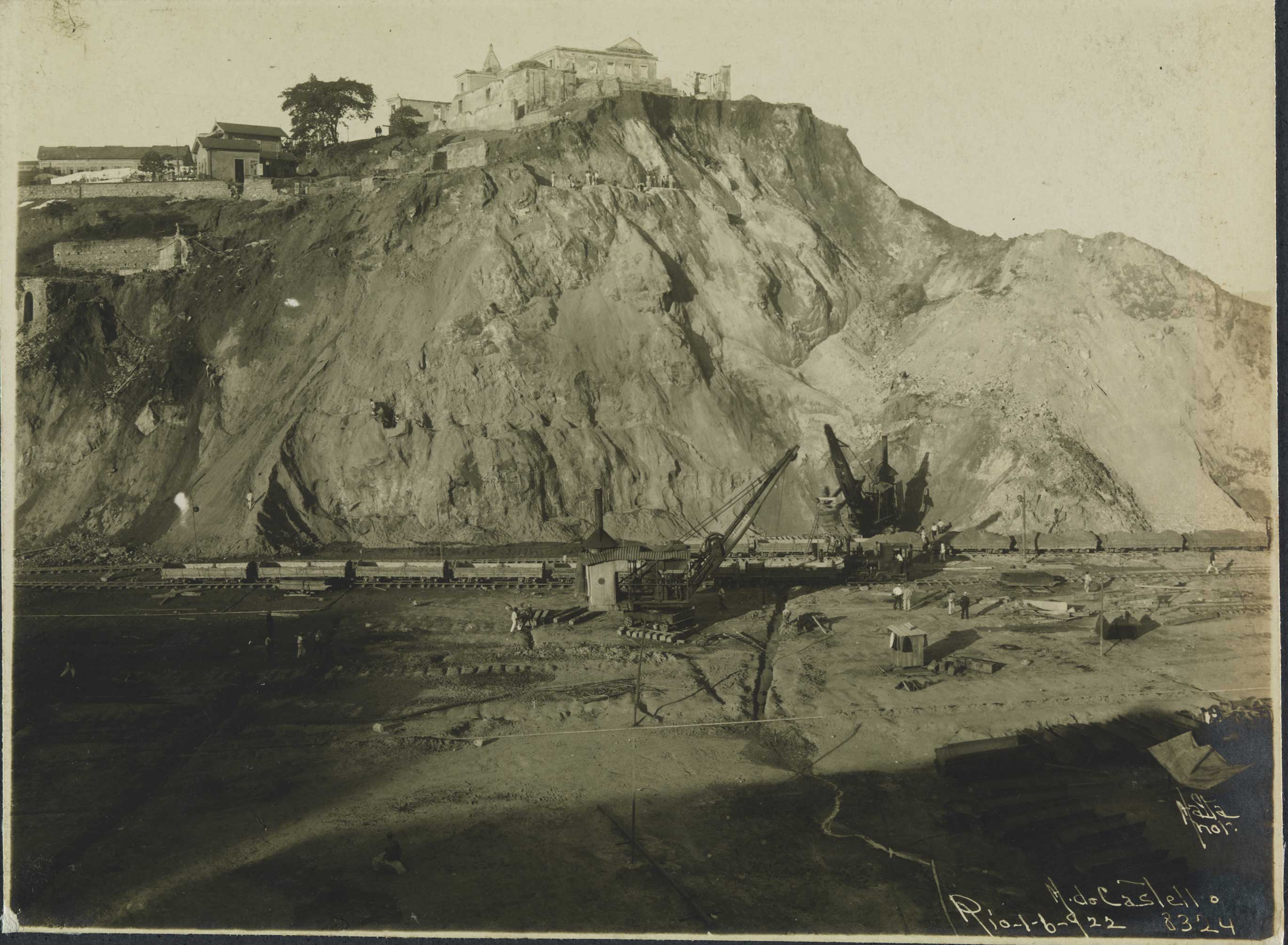

In 1798, the city senate, preoccupied with the sanitary conditions of the city urban center, distributed an official questionnaire to determine the causes of endemic and epidemic diseases affecting Rio’s population. In their response to this questionnaire, the physicians Manoel Joaquim Marreiros, Bernardino Antônio Gomes and Antonio Joaquim de Medeiros blamed the “morros”—the hills that emerged along the city’s bays and valleys—among the main causes that provoked the bad circulation of air and its consequent proliferation of miasmas and other diseases. The physicians also considered that some non-natural factors contributed to the proliferation of diseases, such as the architecture of most of the buildings that were too low-rise, humid, and poorly ventilated. They proposed the elimination of some of the hills and the construction of taller buildings. This questionnaire was first published in 1813, in the scientific and cultural newspaper O Patriota. See Luiz Otávio Ferreira, “Os periódicos médicos e a invenção de uma agenda sanitária para o Brasil (1827-1843),” in Historia Ciencias, Saude—Manguinhos 6, no. 2 (1999): 331–351.

Jose Antonio Nonato and Nubia Melhem Santos, Era uma vez o Morro do Castelo (Rio de Janeiro: IPHAN, 2000), 67.

O Livro de Ouro: Comemorativo do Centenário da Independência do Brasil e da Exposição Internacional do Rio de Janeiro (Rio de Janeiro: Edição do Annuario do Brasil, 1923), 77. Published in conjunction with the Exposição Internacional do Centenário do Brazil (Brazilian International Centennial Exhibition), held in Rio de Janeiro from September 7, 1922 to March 23, 1923.

O Livro de Ouro, 4-5.

The original Tijuca Forest, destroyed by the proliferation of coffee plantations, was replanted during the second half of the nineteenth century with the aim of protecting Rio de Janeiro’s water resources. The Tijuca Forest in Rio covers thirty-two square kilometers, becoming the largest urban forest in the world.

The First Brazilian Congress for the Protection of the Infants was held in Rio de Janeiro from August 27 to September 5 of 1922.

I borrow this association between puericulture and agriculture from Jane Ellen Crisler, “Saving the Seed: The Scientific Preservation of Children in France during the Third Republic.” Ph.D. dissertation. University of Wisconsin-Madison, 1984, 76. For Pinard the term puericulture refers to “the research and application of all knowledge relative to the reproduction, conservation and improvement of the human species” Adolphe Pinard, “De la dépopulation de la France,” Revue Scientifique (July 30, 1910): 30, quoted in Carol, “Médecine et eugénisme en France, ou l rêve d’une prophylaxie parfait. XIXe –Première moitié du XXe siècle,” Revue d’histoire moderne et contemporaine 43 (1996): 618–631.

Christovam Bezerra Dantas, “A Criança e a eugenía” published in the section on Sociology and Legislation in the Primeiro Congresso Brasileiro de Protecção á Infancia, Boletim 7 (1924). Theses officiaes, Memorias e Conclusões. (Rio de Janeiro: Empresa Graphica Editora, 1925), 175–179.

Thomas E. Skidmore’s study “Fact and Myth: Discovering a Racial Problem in Brazil” (São Paulo: Instituto de Estudos Avançados, 1992).

Lucia Silva, “A trajetória de Alfred Agache no Brasil,” in Luiz Cesar de Queiroz Ribeiro and Robert Pechman ed., Cidade, povo e nação: Gênese do urbanismo moderno (Rio de Janeiro: Civilização Brasileira, 1996), 397–410; and Denise Cabral Stuckenbruck, O Rio de Janeiro em questão: o Plano Agache e o ideário modernista dos anos 20, (Rio de Janeiro: IPPUR/FASE, 1996).

Lucio Costa, “O arranha-céu e o Rio de Janeiro,” O País, Rio de Janeiro, July 1, 1928.

Christine Boyer, Le Corbusier: Homme de Lettres (Princeton: Princeton Architectural Press, 2011), 457. See also Wendy Martin, “Remembering the Jungle: Josephine Baker and Modernist Parody,” in Prehistories of the Future: The Primitivist Project and the Culture of Modernism, ed. Elazar Barkan and Roland Bush (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1995), 310-325.

Le Corbusier, The Radiant City (New York: Orion Press, 1967), 115. In the original version in French, Le Corbusier uses the term “puericulture” later translated as “scientific child rearing.” The original quote reads “sont confiées à des infirmières spécialisées surveillées par des médecins: sécurité – sélection – puériculture.”

Le Corbusier, “Aménagement d’une journée équilibrée,” unpublished article, dated May 1932. FCL.UE-5, 64-139.

In his 1945 book, Les Trois établissements humains, Le Corbusier argues: “l’eugénisme, la puériculture, assurant l’élevage d’une race.” Le Corbusier, Les Trois établissements humains (Paris: Les éditions de minuit, 1997), 116.

Le Corbusier, Notes and Sketch (n/d), Foundation Le Corbusier, document F2-17 No. 275.

Alexis Carrel’s 1935 book was simultaneously published in French with the title L’Homme cet inconnu, by Plon in Paris, and in English with the title Man, The Unknown, by the American publisher Harper & Brothers, who also sold the rights to publish condensed chapters of the book in the popular American magazine Reader’s Digest (which by the mid-1930s, had a circulation of over 1.5 million copies), contributing to the commercial success of the book. In this book, Carrel explicitly defends the elimination of defectives and criminals, and even recommends the use of gar chambers to accomplish this goal. See Andrés Horacio Reggiani, “Alexis Carrel, the Unknown: Eugenics and Population Research under Vichy,” French Historical Studies 25 (2002): 331–356.

In June 1927, during his first lecture in Rio, Agache introduced himself as a physician and Rio, Mademoiselle Carioca, as a single woman that required treatment and discipline. Clearly, he conceived his master plan as a medical treatment for a capital city cleansed of diseases and “undesirables,” and therefore suitable for Europeans. Agache argues “I want you to see me as a kind of doctor who has been consulted and who is more than pleased to bring his knowledge to bear and to be able to make use of it in his consideration of this pathological case submitted for examination. I say pathological case because Mademoiselle Carioca is certainly sick. But do not be afraid since her illness is not congenital: it is one that is curable, because it is an illness that consists of a growth crisis… What to do? A physician needs to prescribe a severe regime, a model of progress and discipline, and urgently provide her with a regulatory plan that allows her to blossom favorably.” Donat Alfred Agache, Cidade do Rio de Janeiro. Extensão Remodelação Embellezamento (Paris: Foyer Brésilien, 1930), 5, 21.

Le Corbusier, The Radiant City, 7.

Le Corbusier, Manuscript Lecture I, 5.

Le Corbusier and François de Pierrefeu, The Home of Man, 13.

Le Corbusier, Oeuvre complète 1934-1938 (Zurich: Editions Girsberger, 1953).

This sketch is an adaptation of the one Costa sent to Le Corbusier in July 1937. However, the colossal seated and naked man was already included in a report Le Corbusier submitted to Minister Capanema regarding the construction of the Ministry of Health and Education and the University City Campus for Rio de Janeiro. In this report, dated August 10, 1936, Le Corbusier argues that the ministry building should be built off the coast (at Praia Santa Luzia), rather than on the site of the esplanade proposed by Rio’s Director of Public Works Marques Porto, the site where the Morro do Castelo once stood. Fundação Getulio Vargas, Arquivo Gustavo Capanema, Série F, 34.10.19, II-30, Rio de Janeiro.

Gustavo Capanema, Letter to Getúlio Vargas, dated June 14, 1937. Arquivo Gustavo Capanema, Série F, 34.10.19, III-9, Fundação Getúlio Vargas, Rio de Janeiro.

Gustavo Capanema, Letter to Oliveira Viana dated August 30, 1937, published in Lissovsky and Moraes de Sá, Colunas da Educação, 225.

Ibid., 225–229.

Brazilians saw miscegenation not as a menace but as a solution—as the vehicle for “wiping out the black” and consequently “whitening” the country. Thomas E. Skidmore, Fact and Myth: Discovering a Racial Problem in Brazil (São Paulo: Instituto de Estudos Avançados, 1992).

Edgard Roquette-Pinto, Letter to Gustavo Capanema dated August 30, 1937 published in Lissovsky and Moraes de Sá, Colunas da Educação, 226.

Roquette Pinto was the first anthropologist to create a system of classification of racial types in Brazil. In his paper “Note on the anthropological types of Brazil,” Roquette-Pinto classifies the Brazilian population in four main groups: the “white type” or Leucodermo, representing 51% of the population; the “mulatto type” (descendants of mixing Whites and Blacks) or Phaiodermo, representing 22%; the “Caboclo type” (descendants of mixing whites and indians) or Xanthodermo, representing 11%; and the “Black type” or Melanodermo, representing 14% of the population. As opposed to Oliveira Vianna, Roquette-Pinto rejected the idea that mixed races were degenerated or inferior types, although he accepted that they were, as well as the Blacks and the Indigenous, less beautiful than the Caucasian type. Roquette-Pinto, “Nota sobre os typos anthropológicos do Brasil,” in Primeiro Congresso Brasileiro de Eugenia: Actas e trabalhos, Vol. 1. Rio de Janeiro, 1929, 119–148.

Celso Antônio was Costa’s collaborator in his effort to reform the National School of Fine Arts’ curriculum in the early 1930s. Previously, in the 1920’s, he was a disciple of the celebrated French sculptor Antoine Bourdelle. Costa and Bourdelle recommended Celso Antônio as the project’s sculptor, and in his letter to Capanema, Le Corbusier approved the selection of the Brazilian sculptor to model the “Brazilian Man.” Le Corbusier, Letter to Capanema dated December 30, 1937, published in Lissovsky and Moraes de Sá, Colunas da Educação: A construcão do Ministério da Educação e Saúde (Rio de Janeiro: Fundação Getúlio Vargas CPDOC, 1996), 139-140.

M. Paulo Filho, “Homem Brasileiro,” Correio da Manhã, September 23, 1938, 4.

Le Corbusier, Destin de Paris (Clermont Ferrand, France: Fernand Sorlot, 1941), 60.

Le Corbusier, The Modulor: A Harmonious Measure to the Human Scale Universally Applicable to Architecture and Mechanics (London: Faber & Faber, 1956), 76–80.

Although this work began in the 1920s, it was not until the 1940s that it was codified under the influence of the Commissariat a la Normalisation, the committee for standards of the Order of Architects. Jean-Louis Cohen, “Le Corbusier’s Modulor and the Debate on Proportion in France,” Architectural Histories, 2 (2014).