Lu Xun, “Yao” (“Medicine”), Xin Qingnian / La Jeunesse (Xin Qingnian) 6, no. 5 (1919), unpaginated.

Carlos Rojas, Homesickness: Culture, Contagion and National Transformation in Modern China (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2015); Yang Nianqun, Remaking Patients: Space Politics under the Conflict between Chinese and Western Medicine (1832-1985) (New York: Peter Lang, 2020).

Beatriz Colomina, X-Ray Architecture (Zürich: Lars Müller Publishers, 2019).

Yongyi Lu and Yan Chen, “The Idea and Form of Functionalism in early Chinese Modern Architecture: A Case Study on Hongqiao Sanatorium in Shanghai,” Jianzhu shi (October 2017), 49–58.

Jianfei Zhu, Architecture of Modern China (London; New York: Routledge, 2009), 71.

Although the Qing dynasty was toppled in 1911, China was not unified until 1928, when the KMT was finally able to consolidate its control over most of the country and relocated the capital from Beijing to Nanjing, ushering in an era of relative stability before the outbreak of the Sino-Japanese war in 1937. The notion of the architect as an individual artist did not exist in China before the twentieth century. The emergence of the architectural profession is also manifested in an epistemological shift of the concept of architecture. The traditional term for architecture, yingzao, was replaced by a new term, jianzhu, to emphasize the new notions of architecture as an art, a discipline and a profession (as opposed to a craft).

Lai Delin, Zhongguo Jindai Jianzhu Shi Yanjiu (Studies in Modern Chinese Architectural History) (Beijing, Qinghua Daxue Chubanshe, 2007).

To be clear, this reinvented “Chinese architectural tradition” is a modern construction underpinned by the Beaux-Arts tradition and various Western architectural theories such as structural rationalism and organicism, and its development involved a history of orientalist scholarship and a legitimizing process in which Western architecture was taken as the universal point of reference. However, it has been deemed to be “traditional” by reformers and historians in pursuit of a Western-centric notion of modernity. Chinese Architecture and the Beaux-Arts, Jeffrey W. Cody, Nancy S. Steinhardt, and Tony Atkin, eds. (Honolulu: University of Hawaiʻi Press, 2011).

Sean Hsiang-lin Lei, Neither Donkey Nor Horse: Medicine in the Struggle over China’s Modernity (Chicago; London: The University of Chicago Press, 2014), 116.

Bridie Andrews, The Making of Modern Chinese Medicine, 1850-1960 (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2014), 122–133.

Lei, “Habituating Individuality: The Framing of Tuberculosis and Its Material Solutions in Republican China,” 255.

In his 1923 proposal for creating a department of hygiene at the Peking Union Medical College (PUMC), John B. Grant, a professor at PUMC and the representative of the International Health Board of the Rockefeller Foundation, argued against implementing tuberculosis control at the early stage of managing public health in China. While Grant estimated that China had an extremely high death rate of fifteen per thousand, he maintained: “In China, where funds and personnel are limited, it would be unwise to concentrate inadequate resources on tuberculosis until the attack on the more easily controllable gastro-intestinal diseases had been well organized.” This proposal was readily accepted by the government. John B. Grant, “A Proposal for a Department of Hygiene” (1923), Rockefeller Foundation Archives, Rockefeller Archive Center, Sleepy Hollow, New York (hereafter RAC), box 75, folder 531, p. 17. Quoted in Sean Hsiang-lin Lei, “Habituating Individuality: The Framing of Tuberculosis and Its Material Solutions in Republican China.” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 84, no. 2 (2010): 253.

Ibid., 256.

Despite being called “national,” the range of their impact was relatively local and concentrated in the Shanghai region.

Lei, “Habituating Individuality: The Framing of Tuberculosis and Its Material Solutions in Republican China.”

Ge Chenghui, “Zhongguoren yu jiehebing” (The Chinese and tuberculosis), Kexue (Science) 10 no. 5 (1935): 587–96. Quoted in Lei.

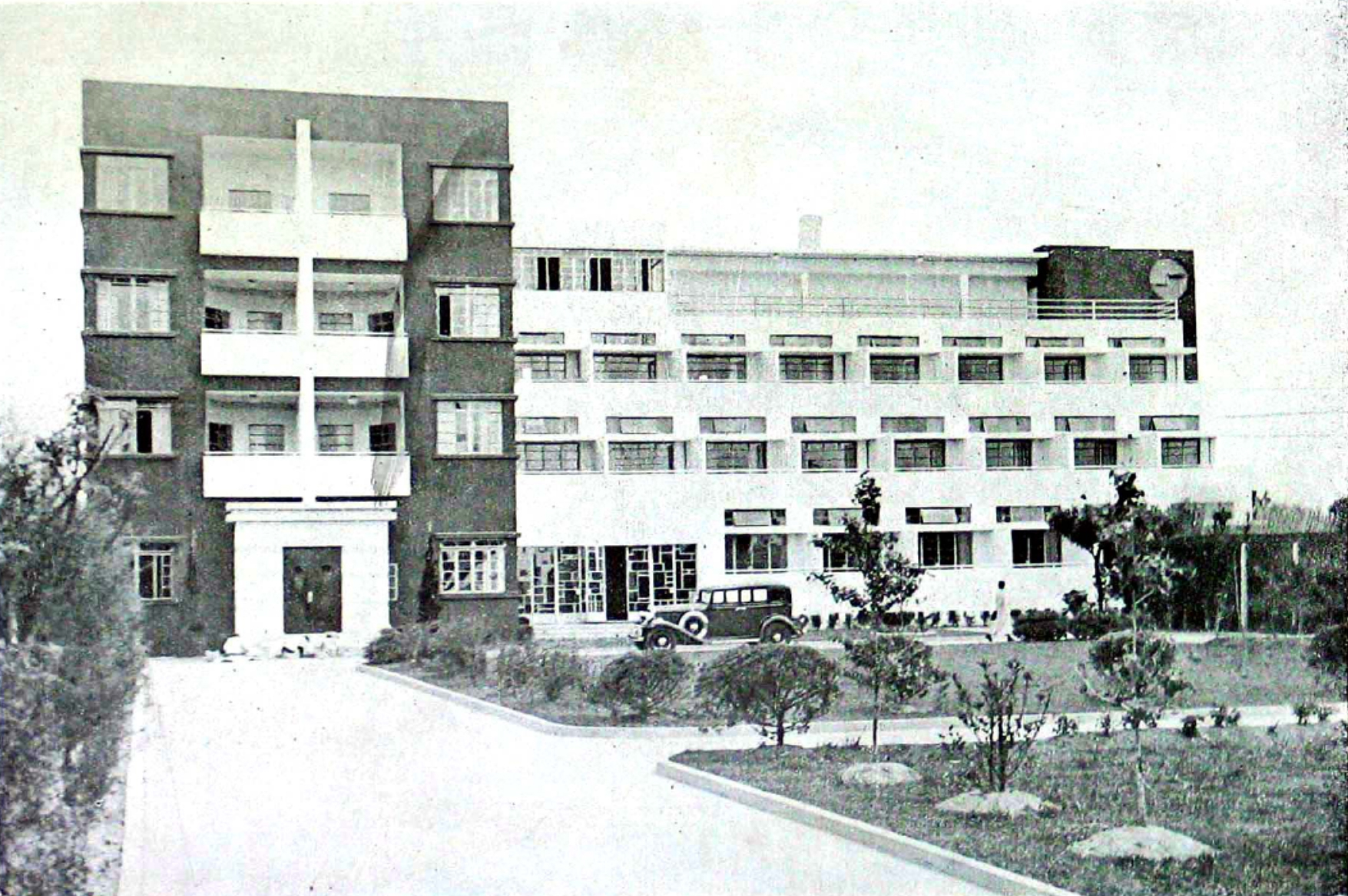

“New Sanatorium Opened, Hungjao Institution Presents Many Modern Features,” The North-China Herald and Supreme Court & Consular Gazette, June 20, 1934: 430.

The China Times (June 16, 1934), 2.

The China Times (June 10, 1934), 9.

Fuquan studied under the name Fohzien Godfrey Ede, he received his Diploma in engineering from Technische Hochschule zu Darmstadt in 1926, and his doctorate in engineering under the direction of architectural historian and Sinologist Ernst Boerschmann from Technische Hochschule zu Charlottenburg in 1929. Eduard Kögel, “Early German Research in Ancient Chinese Architecture (1900–1930),” Berliner Chinahefte/Chinese History and Society 39 (2011): 81–91.

Shi shi xin bao, December 21, 1934.

“New Sanatorium Opened, Hungjao Institution Presents Many Modern Features,” 430.

Shi shi xin bao, June 26, 1934.

Alys Eve Weinbaum, Lynn M. Thomas, Priti Ramamurthy, Uta G. Poiger, Madeleine Yue Dong, and Tani Barlow, eds., The Modern Girl Around the World: Consumption, Modernity, and Globalization (North Carolina: Duke University Press, 2008.)

Syed Raza Hassan, “Pakistan says trial of Chinese traditional medicine for COVID-19 successful,” Reuters (Jan. 17, 2022), ➝; Zhuang Pinghui, “World Health Organization Chief Given Report on Use of Traditional Chinese Medicine in Fighting Covid-19,” South China Morning Post (Jan. 21, 2022), ➝; Victoria Amunga, “China Exports Its Traditional Medicine to Africa,” VOA News (Jan. 21, 2022), ➝; Ian Johnson, “Chinese Medicine in the Covid Wards,” The New York Review (Nov. 4, 2021), ➝.