Erich Fromm, The Sane Society (New York: Rinehart & Company, Inc., 1955).

Günther Anders and Claude Eatherly, Burning Conscience (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1962). Major Claude Eatherly, whom Anders met and exchanged letters with, was, having dropped the bomb, the “hero of Hiroshima.” Yet after the war, he behaved quite unlike a hero, having attempted suicide, getting arrested for suspicion of theft, and ultimately being diagnosed with schizophrenia. Through his interaction with Eatherly, Anders came to think that his schizophrenia was caused by a fragmented society. It is natural for someone who murdered tens of thousands of civilians by dropping an atomic bomb to suffer from guilt, but American society put him on a pedestal as a hero who brought victory to America. At the same time, there was not a small amount of criticism about the bombing. He was agonized amid these conflicting messages and finally became schizophrenic. According to Anders’s interpretation, the solution that would allow him to escape the role of a gear in the “war machine” was schizophrenia.

Criticism of Bettelheim’s theory started to appear in the mid-1960s. Bernard Rimland, a psychologist, psychiatrist, and a parent to an autistic child, made an effective argument in Infantile Autism (1964) based on his experience and research that autism had no relation with apathetic mothers.

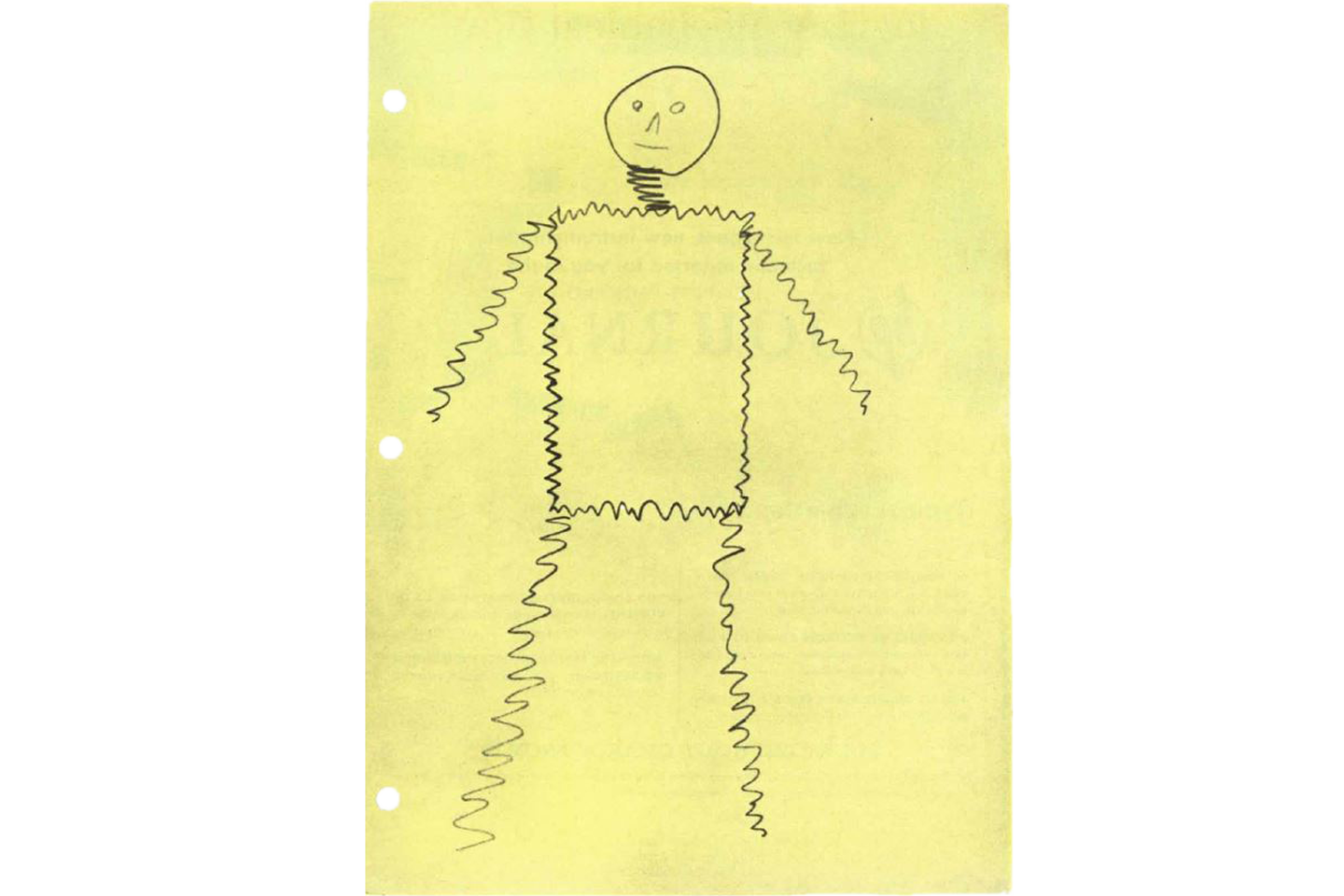

Bruno Bettelheim, “Joey, A ‘Mechanical Boy,’” Scientific American 200 (March 1959).

Bruno Bettelheim, The Empty Fortress: Infantile Autism and the Birth of the Self (Glencoe: Free Press, 1967), 234.

Ibid., 336–37.

Superhumanity: Post-Labor, Psychopathology, Plasticity is a collaboration between the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea and e-flux Architecture.