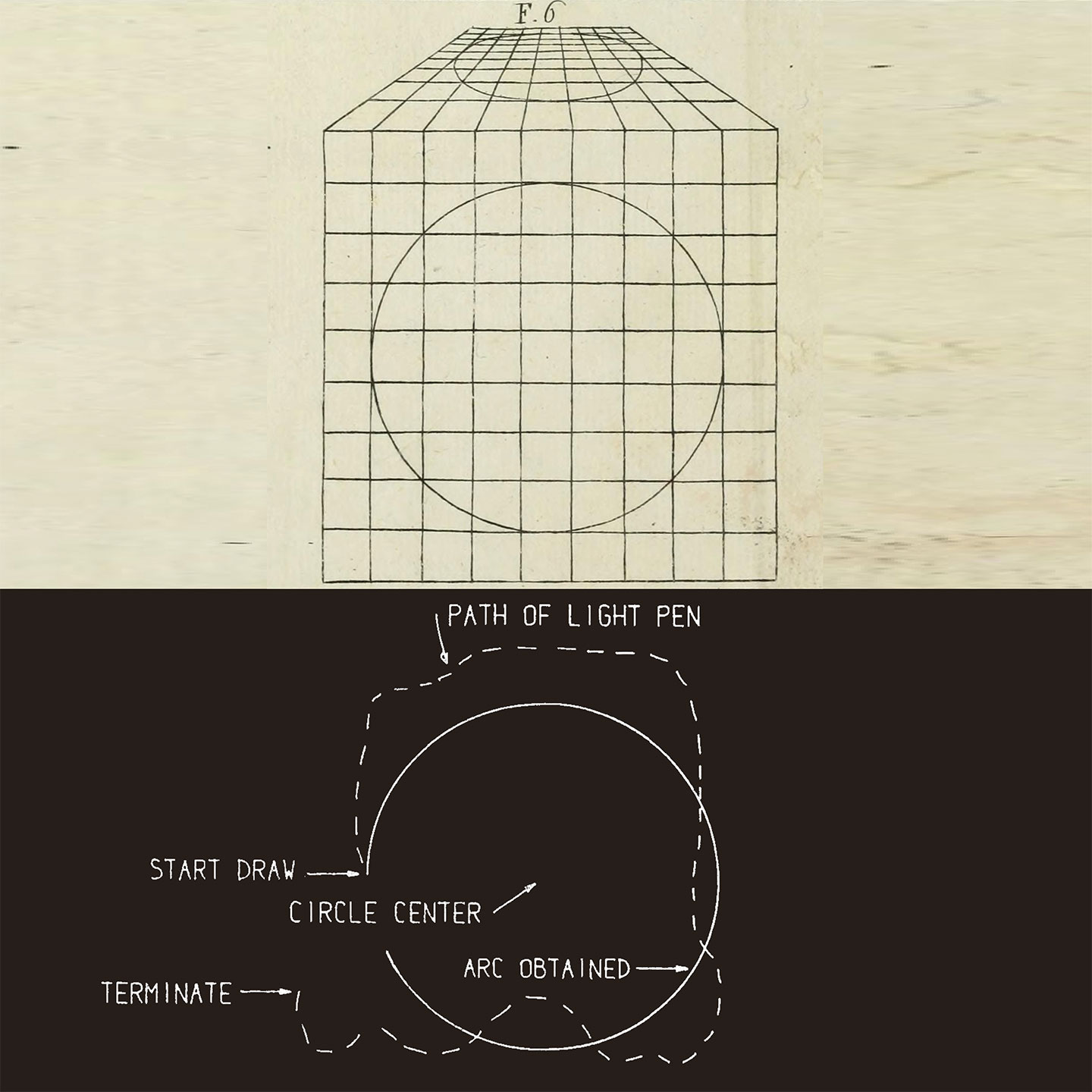

“As it would be an immense labor to cut the whole circle at many places with an almost infinite number of small parallels until the outline of the circle were continuously marked with a numerous succession of points, when I have noted eight or some other suitable number of intersections, I use my judgement to set down the circumference of the circle in the painting in accordance with these indications.” Leon Battista Alberti, On Painting, ed. Martin Kemp (London: Penguin Classics, 1991), 71.

With this you really do not need to be able to draw a circle to draw a circle, indeed you only need to intend a circle. Ivan Sutherland, “Sketchpad: A Man-Machine Graphical Communication System,” The New Media Reader, ed. Wardrip-Fruin and Montford (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2003), 111. My emphasis.

“I did a thing that I called ‘pseudo-gravity’ which said that around lines or around the intersection between lines that the light pen would pick up light from those lines and then the computer would do a computation saying: ‘Gee, the position of the light pen now is pretty close to this line, I think what the guy wants is to be exactly on this line’, and so what would happen is that if you moved the pen near to an existing part or near to an existing line it would jump and be exactly at the right coordinates.” Sketchpad, lecture by Ivan Sutherland, 3 March 1994, Bay Area Computer Perspectives, No. 102639871. US: Sun Microsystems, 1994.

Ibid., Sutherland, New Media Reader, 113.

MIT Science Reporter: Computer Sketchpad, John Fitch, Dir. Russell Morash, WGBH-TV, Boston (21 mins.), 1964.

I am here indebted to Gergely Kovács and to our AA students with whom I have shared numerous conversations regarding the history of the algorithm.

We can find this corrective architecture’s nascent circulatory logics as far back as in the search and retrieval pathways of the memory in Aristotle, the mnemonic architectures of Cicero and Quintilian, and their Renaissance theatrical progeny by Giulio Camillo and Robert Fludd; its exhaustive (but never exhausted) recursive organization in the design of the penance directing wings of Alan of Lille’s Medieval six-winged seraphs; its ambitions for omniscience through radical reduction—one system that could process all data and thus hold all knowledge—in the wheels (the footprint of the machine was there already) of Ramon Lull and Giordano Bruno; and then, as machine met language, in the Universal Languages of John Wilkins, Francis Bacon and Gottfried Leibniz et al. See Mary Carruthers, The Book of Memory: A study of Memory in Medieval Culture, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 1990); The Medieval Craft of Memory: an Anthology of Text and Pictures, eds. Carruthers & Jan M. Ziolkowski (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2002); Frances A. Yates, The Art of Memory (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1966).

Harald Weinrich, Lethe: the Art and Critique of Forgetting (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2004).

See Pedro Domingos, The Master Algorithm: How the Quest for the Ultimate Learning Machine will Remake our World (New York: Basic Books, 2015).

Or to correct society in general: in the US an algorithm is being used to help judges granting bail to predict who is likely to succumb to recidivism. Meanwhile, the echo-chambers of news-tailoring algorithms are personalizing the correction of our world-view with unintended consequences. See: “The Power of Learning,” The Economist (20 August 2016), 11.

Paolo Rossi, Clavis Universalis: Arti Della Memoria e Logica Combinatorial da Lullo a Liebniz (Milan: R. Ricciardi, 1960).

Ibid., Yates, 175.

Among them: Johann Alsted, Robert Boyle, Giordanno Bruno, Giulio Camillo, Arthur Collier, Jan Amos Comenius, George Dalgarno, Thomas Hobbes, Sebastiano Izquierdo, Athanasius Kircher, Petrus Ramus, John Ray, Giambattista Vico and John Wilkins. Ibid., Rossi, xxii.

Johann Heinrich Alsted cited in Ibid., Rossi, 132.

George Dalgarno cited in Ibid., Rossi, 158.

Francis Bacon cited in Ibid., Rossi, 148.

Robert Boyle cited in Ibid., Rossi, 152.

The titles of a sample of the artificial languages published during this period speak volumes: The Groundwork of Foundation Laid (or so Intended) for the Framing of a New Perfect Language, Francis Lodowick, 1652; Logopandecteision, or an Introduction to the Universal Language, Thomas Urquhart, 1653; The Universal Character by which all Nations may Understand One Another’s Conceptions, Cave Beck, 1657.

John Wilkins, who whittled his Language down to three thousand “words,” declared that they could be learnt in only two weeks, and that one could achieve a level of fluency in one year that would take forty years to achieve in Latin.

Gottfried Leibniz cited in Ibid., Rossi, 182.

Denis Diderot and Jean le Rond d’Alembert, “Histoire Naturelle,” Encyclopédie, ou Dictionnaire raisonné des Sciences, de arts et des métiers, par une societ´de gens de lettres, Vol VII (Paris: 1751), 230.

Superhumanity, a project by e-flux Architecture at the 3rd Istanbul Design Biennial, is produced in cooperation with the Istanbul Design Biennial, the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea, the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, New Zealand, and the Ernst Schering Foundation.