Maruboshi was a rail freight transportation and cargo unloading company that operated in every railroad station in colonial Korea. After liberation, it was classified as an enemy business and was nationalized. In 1962, it became Korea Transportation Ltd. (now Korea Express) and merged with Joseon Rice Warehousing.

Antonio Gramsci, Selections from the Prison Notebooks, (New York: International Publishers, 1971), 276.

Richard F. Calichman, What is Modernity? Writing of Takeuchi Yoshimi, (New York: Columbia University Press, 2005). For a discussion of universalism and particularism of the West and East in modern knowledge, see Naoki Sakai, “Dislocation of the West and the Status of the Humanities,” Traces 1: A Multilingual Journal of Cultural Theory and Translation, Specters of the West and Politics of Translation, (2001); 71-94.

“Ephemera Orientalis McLachlan (...) is a common burrowing mayfly which is found distributed throughout temperate East Asia including northeastern China, Mongolia, the Russian Far East, the Korean Peninsula, and the Japanese Islands (Hwang et al. 2008). The larvae occur abundantly in the lower reaches of streams, rivers, and lentic areas such as lakes and reservoirs, and are becoming more important in the biomonitoring of freshwater environments. The mass emergence and light attraction behavior of this species during the late spring and summer seasons, however, frequently causes serious nuisance to people residing in towns and cities near streams and rivers. This species is particularly abundant in the Han River that runs across Seoul and the frequency and intensity of its mass emergence has evidenced an increase in recent years.” Jeong Mi Hwang, Tae Joong Yoon, Sung Jin Lee and Yeon Jae Bae, “Life history and secondary production of Ephemera orientalis (Ephemeroptera: Ephemeridae) from the Han River in Seoul, Korea,” Aquatic Insects, Vol. 31, Supplement 1, (2009) 333–341, ➝.

The nutria (Myocastor coypus), also known as river rat, was first imported in Korea in 1987 from Bulgaria for meat. They were initially farmed in Yongam-ni, Seosan-gun, South Chuncheong Province. However, the nutria meat business did not quite take off in Korea, and thus nutria farmers began abandoning the business and releasing the giant rats into the wild. The rats have now become a serious threat to the environment and are being hunted and killed.

She describes the wax figure in the Musée Gravin as a “Wish Image as Ruin: Eternal Fleetingness,” that “No form of eternalizing is so startling as that of the ephemeral and the fashionable forms which the wax figure cabinets preserve for us. And whoever has once seen them must, like André Breton (Nadja, 1928), lose his heart to the female form in the Musée Gravin who adjusts her stocking garter in the corner of the loge.” Susan Buck-Morss, The Dialectics of Seeing: Walter Benjamin and the Arcades Project (Cambridge, Mass. and London: MIT Press, 1991), 369.

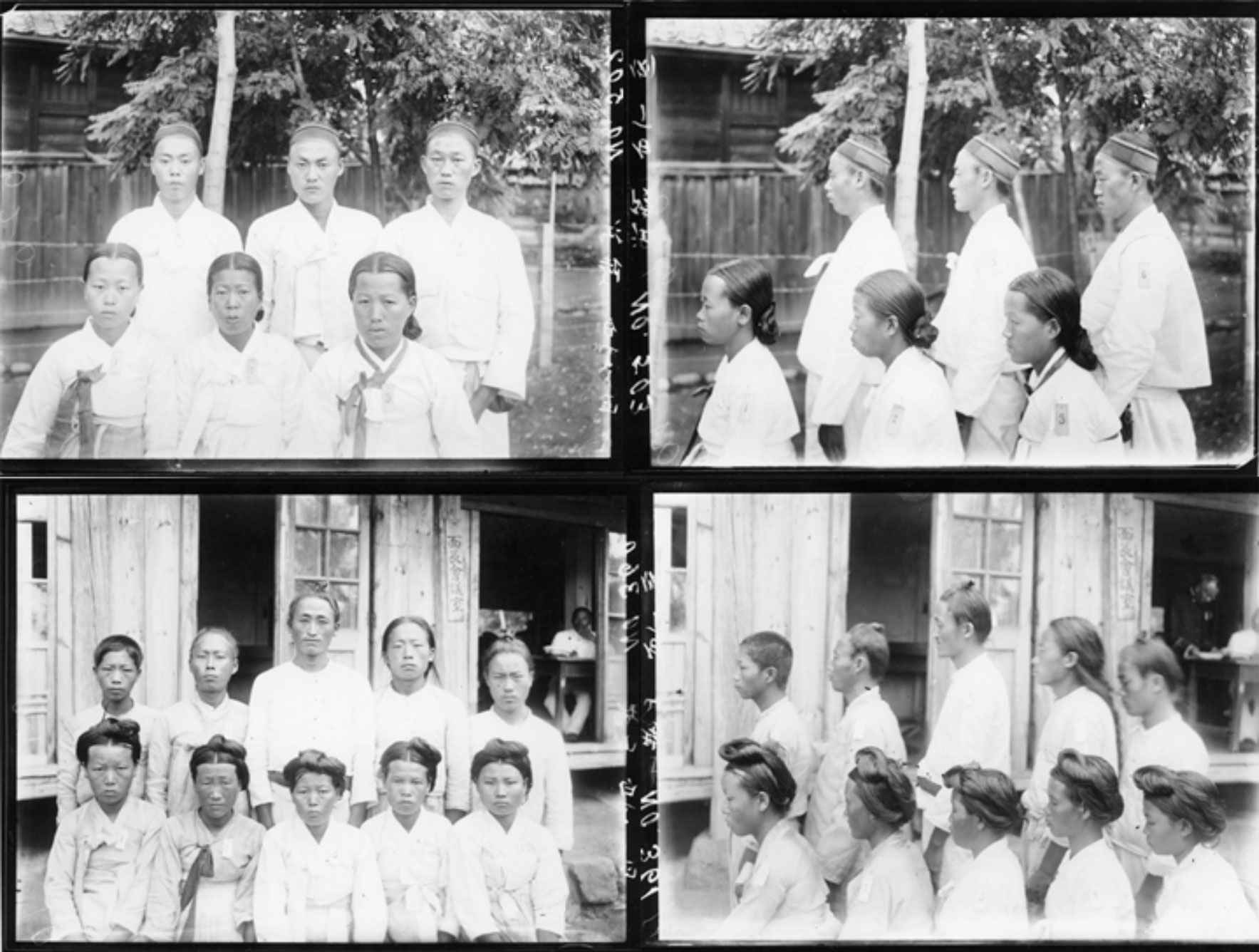

For more reference about the colonial anthropology and its tactics during the Imperial era, see Sakano Tohru, Teikoku Nihon to Junyuigakusha (Imperial Japan and Anthropologists) (Tokyo: Keiso Shobo Publishing, 2005) and Wartime Japanese Anthropology in Asia and the Pacific, eds. Akitoshi Shimizu and Jan van Bremen, (Osaka: National Museum of Ethnology: 2003).

Homi K. Bhabha, The Location of Culture (London: Routledge, 1994).

The term “ethnic abjection” was first used by Rey Chow in “The Secret of Ethnic Abjection.” Postcolonial theories have contributed to the global spread of the discourse of hybridity and cultural diversity as counter narratives to trans-nationalism and globalization. “Ethnic abjection” refers to the identity of heterogeneity that is being artfully concealed within this counter-discursive frame and the emotional structure of the ambiguity, rage, pain, and melancholy brought about by the politics of recognition. Rey Chow, “The Secret of Ethnic Abjection,” Traces 2: A Multilingual Journal of Cultural Theory and Translation, Specters of the West and Politics of Translation, (2001); 53-77.

During the Park Chung-hee dictatorship in 1960s-1970s, North Koreans were frequently represented in popular media as animals such as rats, pigs, wolves, and foxes, and became associated with the hatred and negative symbolism that these animals carry for their potential to spread infectous disease, such as typhus and epidemic hemorrhagic fever. In so doing, anti-communist narratives constituted an uncanny heterogeneous contemporaneity with the culture of (post-)colonial Japanese. Therefore, various class, gender and ethnic-based narratives suddenly become sutured under the rubric of modernization and national security.

The Sewol Ferry incident occurred on 16 April 2014 and killed more than 300 people, mostly high school students on the school trip going to Jeju Island. It is seen as a disaster that resulted from the combination of the government’s lack of effort, evasion of responsibility and mishandling of a very preventable disaster. The disaster created an outrage in South Korea and created a demand for special legal investigation of the disaster to reveal and bring to justice parties who were responsible for the sequence of events. This demand, however, was met with disappointing response from the government, being misrepresented and mis-portrayed as an effort to shift blame to the victim’s families and suppress the protests.

This term is borrowed from Andreas Huyssen, with which he tries to explain the academic discussion and exhaustion of topics of memory. Andreas Huyssen, Present Pasts: Urban Palimpsests and the politics of memory, (Stanford: Stanford University Press: 2003), 3.

These questions are proposed by Judith Butler in drawing on Agamben’s notion of bare life to the post-9/11 Iraq war America. Judith Butler, Precarious Life: The Powers of Mourning and Violence (London: Verso, 2006), 20.

Among the places where the animals were buried alive, there were many sites that did not obey the instructions to install basic facilities such as drainage with perforated drainpipe. See ➝.

For Agamben, the wolf symbolizes a metonym of the return of the primitive in the collective unconscious, as what he describes “a monstrous hybrid of human and animal.” He said “what had to remain in the collective unconscious as a monstrous hybrid of human and animal, divided between the forest and the city – the werewolf – is, therefore, in its origin the figure of the man who has been banned from the city. (…) The life of the bandit, like that of the sacred man, is not a piece of animal nature without any relation to law and the city. It is, rather, a threshold of indistinction and of passafe between animal and man, physis and nomos, exclusion and inclusion: the life of the bandit is the life of the loup garou, the werewolf, who is precisely neither man nor beast, and who dwells paradoxically within both while belonging to neither.” Giorgio Agamben, Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life, trans. Daniel Heller Roazen, (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1998), 105.

“The punctum of the uncanny” is a phrase Hal Foster uses in reference to Roland Barthes’s concept of “punctum.” Barthes speaks of “the tactile trace, the marks that photography leaves on our body.” Foster is referring to the uncanny feeling one gets from objects that seem to actually exist. This is related to the Freudian “return of the repressed,” or the unconscious desire to return to the state of not knowing the distinction between life and death, between organism and inorganic substance. Hal Foster, Compulsive Beauty, (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1993).

Superhumanity, a project by e-flux Architecture at the 3rd Istanbul Design Biennial, is produced in cooperation with the Istanbul Design Biennial, the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea, the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, New Zealand, and the Ernst Schering Foundation.