Roland Burrage Dixon, The Mythology of All Races: Oceanic, vol. IX (Boston: Marshall Jones, 1916), 15.

Katherine Harmon Courage, “How the Freaky Octopus Can Help Us Understand the Human Brain,” Wired, October 1, 2013, ➝.

Edward J. Steele et al., “Cause of Cambrian Explosion—Terrestrial or Cosmic?” Progress in Biophysics and Molecular Biology 136 (August 2018): 3–23.

Courage, “How the Freaky Octopus Can Help Us.”

Donna Haraway, Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene (Durham: Duke University Press, 2016).

Ibid., 50.

Ibid., 71.

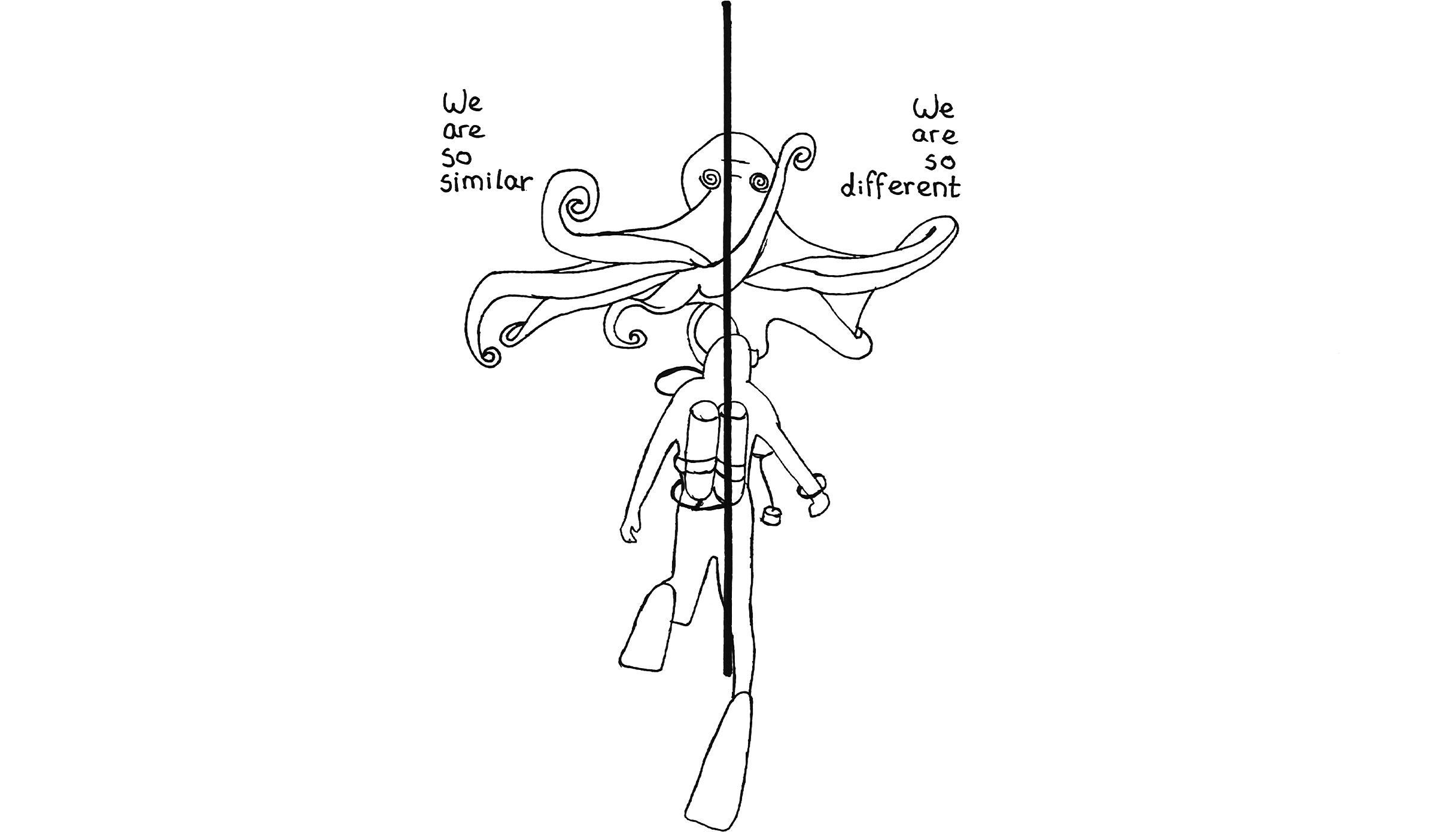

The abundance of octopus stories are not only found in ancient Greek myths, seafarer tales, and indigenous creation stories, but also pornographic imagery, contemporary fiction, children’s stories, scientific texts, and documentaries.

David Abram, Becoming Animal: An Earthly Cosmology (New York: Vintage Books, 2010), ix.

Amba J. Sepie, “More than Stories, More than Myths: Animal/Human/Nature(s) in Traditional Ecological Worldviews,” Humanities 6, no. 78 (2017): 1–31. See also Deborah Bird Rose, “Val Plumwood's Philosophical Animism: Attentive Interactions in the Sentient World,” Environmental Humanities 3, no. 1 (2013): 93–109.

Eva Meijer, When Animals Speak: Toward an Interspecies Democracy (New York: New York University Press, 2019), 239.

For more on animals as world-makers, see Anna Tsing, The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2015), 22.

The work of philosopher Vinciane Despret, specifically her 2016 book What Would Animals Say If We Asked the Right Questions, illustrates many scientific stories in which various animals have changed the course of traditional scientific procedures. Despret’s work thereby shows that inherent differences between living beings of any kind do not hold still as facts, but that we can continuously challenge them. She writes, “Beyond these reversals, these stories fall within a very similar regime: one that characterizes situations in which beings learn either to ask that what matters to them be taken into account or to respond to such a demand. And that they learn to do so with another species.” Vinciane Despret, What Would Animals Say If We Asked the Right Questions, trans. Brett Buchanan (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2016), 20. Such stories, in the sciences, are often accused of anthropomorphism, in the sense that our interpretations risks humanizing other animals’ behaviours and intentions and thereby fail to account for the animal’s actual life worlds. However, the paradox that Bruno Latour lays out in the foreword of this book is the idea that anthropomorphism can be avoided through strictly controlled scientific methods: “only by creating the highly artificial conditions of laboratory experimentation will you be able to detect what animals are really up to when freed from any artificial imposition of human values and beliefs onto them. From then on, only one set of disciplined accounts of what animals do in those settings will count as real science. All other accounts will be qualified as ‘stories.’” Bruno Latour, “Foreword: The Scientific Fables of an Empirical La Fontaine,” in Despret, What Would Animals Say, viii. This, according to Despret, leads more to a kind of academocentrism, where the naturally occurring situations are considered a source of artificial fictions.

Stephen Johnson, “Watch: Octopus changes colors while (possibly) dreaming,” Big Think, September 27, 2019, ➝.

Elizabeth Preston, “Was Heidi the Octopus Really Dreaming?” New York Times, October 8, 2019, ➝.

Sy Montgomery, “Deep Intellect,” Orion Magazine, October 2011, ➝.

See Michelle Westerlaken, “Imagining Multispecies Worlds” (PhD diss., Malmö University, 2020), ➝.