In the last few decades, new approaches have been taken to address the urban and territorial impact of public works in Chile, particularly in their relation to natural environments and originary populations. One leading example of this is the development and implementation of the Indigenous Architectural Design Guides by the Department of Architecture, Ministry of Public Works, the first Aymara and Mapuche editions of which were published in 2004, and revised in 2016.1 Their purpose was to include the worldview of First Nations in public buildings and to build works that are pertinent to their culture and cosmology.2

I was invited to develop this idea by the Department of Architecture in 2000, after a TV report featured my diploma project for an Indigenous Cultural Institute in Santiago, Chile. In those years, there was a growing sense of empowerment in the Indigenous movement as its leadership acquired some degree of influence within the government’s “New Deal Policy Towards Indigenous Peoples.” This framework entailed a series of initiatives for inclusion and recognition of Indigenous matters in various spheres of state control, including the design and construction of public buildings.

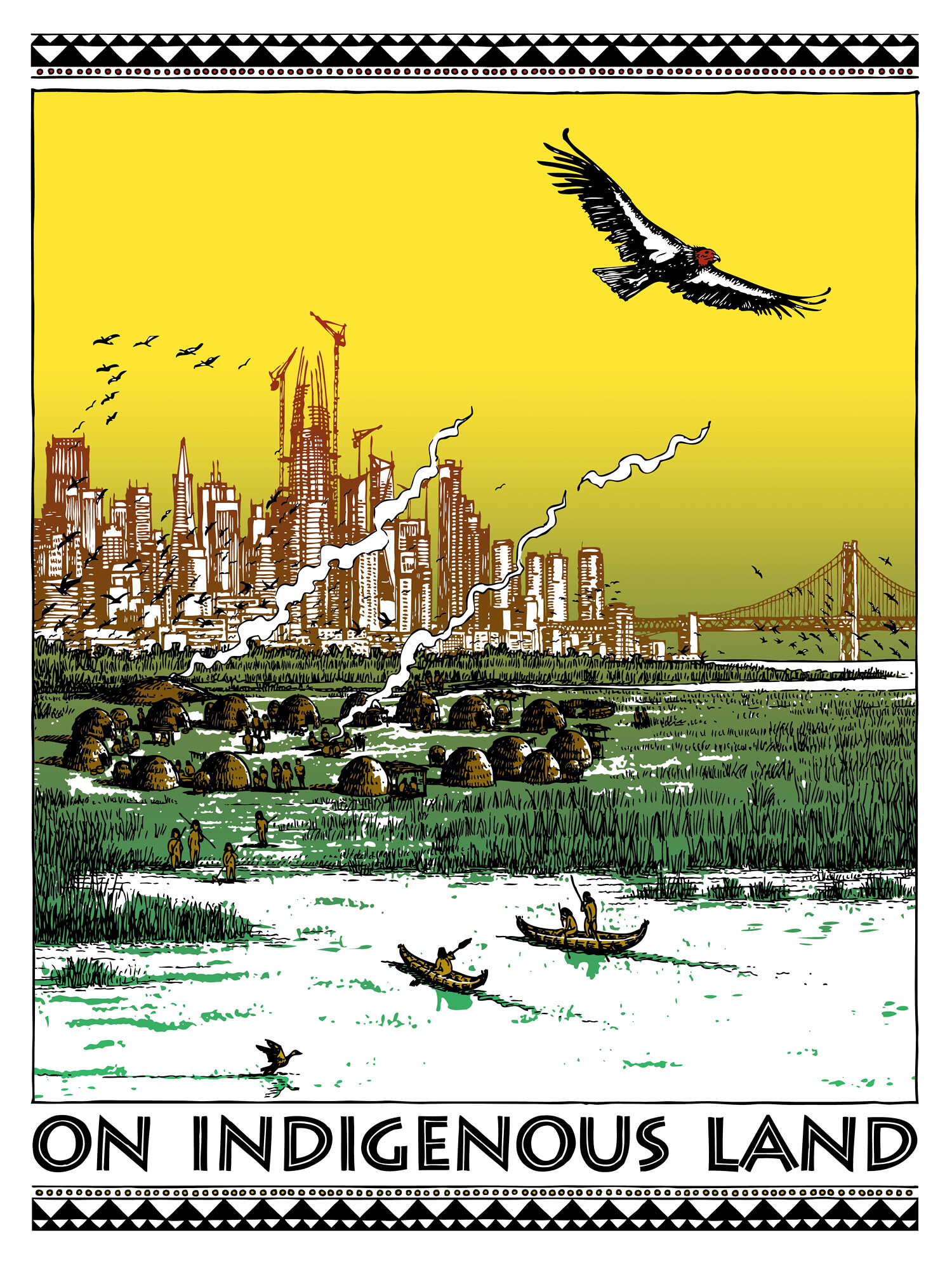

In Chile, the complex relationship between the state and First Nations devolves, from time to time, into acts of violence. Such events dilute expectations for advancement in the development, rights, and social cohesion of Indigenous populations, and expose underlying prejudices, denial, and even racism that have yet to be addressed. When large public works for connectivity, energy generation, or productive infrastructure affect the traditional territories of Indigenous peoples, they become a source of conflict over rights and power differentials. Opposing visions of development not only reveal an unresolved relationship between the state and Indigenous peoples, but also within society as a whole.

The situation is somewhat different in the case of public buildings, which have a more localized impact and a more explicit focus on human development and access to public services. Here, Indigeneity serves as a pretext and opportunity for the effective intervention of public service, as well as the source of its main difficulties—namely, lack of participation and insufficient information to know about and plan for architectural solutions that will have the most positive effect on Indigenous development or intercultural spaces. Nevertheless, as public spaces, public buildings embody the debate over the identity of what we share and what distinguishes us, what belongs and what does not, what is included and what is excluded.

For architect and urbanist Fernando Carrión, public space “is a form of representation of the collectivity as well as an element that defines collective life… public space is the space of the pedagogy of otherness, because it makes possible the encounter between heterogeneous manifestations, the potential for social contact, and the generation of identity.”3 Institutions that formulate and design public spaces and public buildings, therefore, have a responsibility to process differences and promote tolerance.

To date, about twenty public works have, in one way or another, followed the approach towards Indigenous cultural relevance set out in the Design Guides. These works include student homes, hospitals, high schools, cultural centers, municipal buildings, and public spaces. Sixteen years after the Design Guides were first published, certain challenges and limitations can be recognized in their legacy, which also offers further opportunities for reflection. To what extent do public buildings constitute a factor of development for First Nations? In what form might architectural design contribute to the “pedagogy of otherness,” constructing an urban and territorial environment of greater cohesion and social justice in an intercultural Indigenous context?

Guías de Diseño Arquitectónico Aymara and Guías de Diseño Arquitectónico Mapuche, 2016. Courtesy of Ministerio de Obras Públicas, Dirección de Arquitectura.

Indigenous Inclusion in Architectural Design

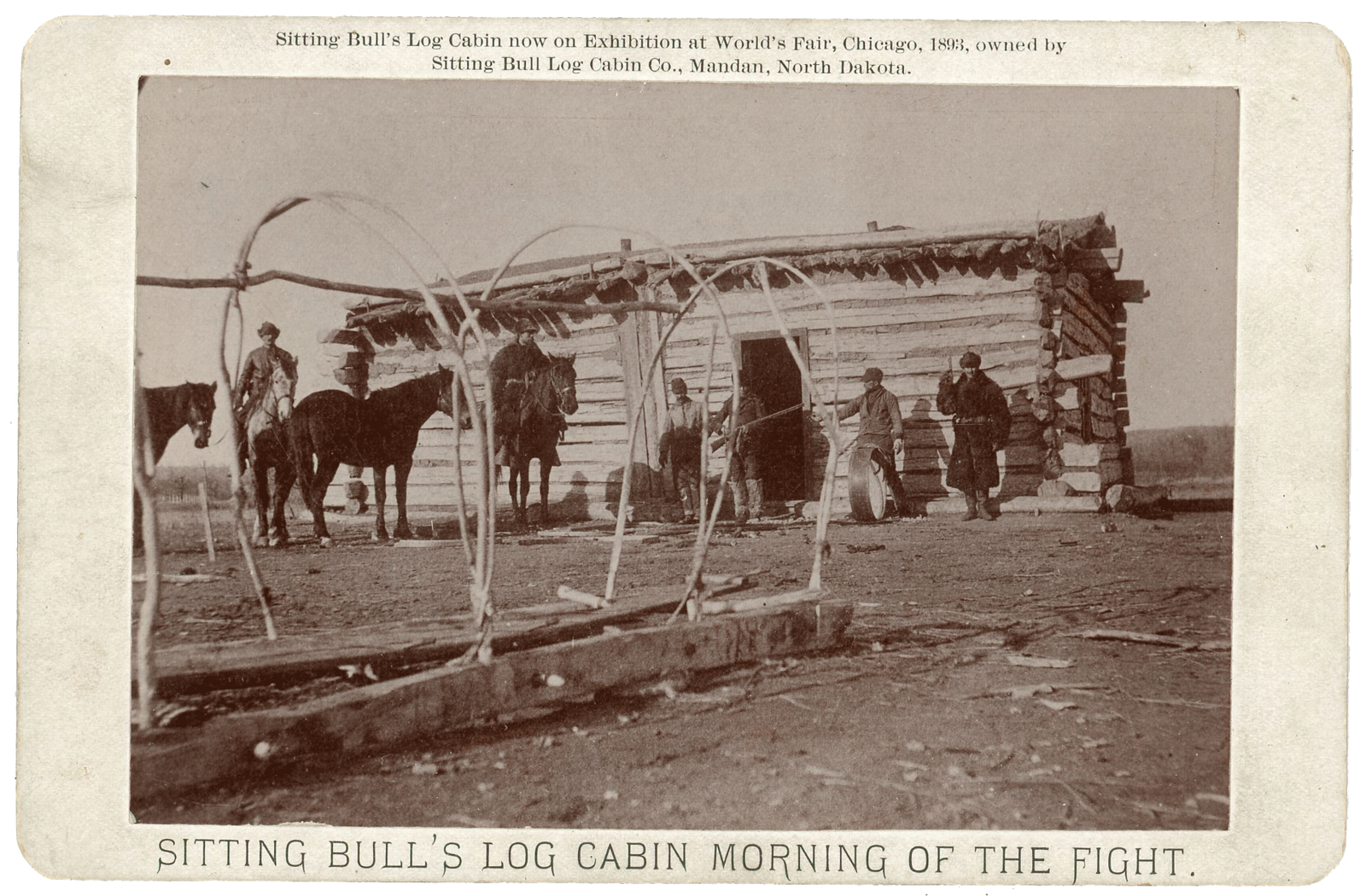

The process of conceiving a modern building in Chile based on the reflections and study of Indigenous culture and forms of life is relatively rare, but not unprecedented. During the Art Deco period in Santiago in the 1930s, the iconography of Indigenous peoples was incorporated by architects into the public buildings that now constitute the city’s patrimony. This represented a break with the historicism of the elites of the time, and formulated the question of national identity in an architectural language. The past few decades have seen the construction of a number of Indigenous, and namely Mapuche public buildings, such as the Mapuche Museum of Cañete (1977), the headquarters of the Institute of Indigenous Studies at Universidad de La Frontera in Temuco (1994), and the Afunalhue Center at the Catholic University in Villarrica (1997).

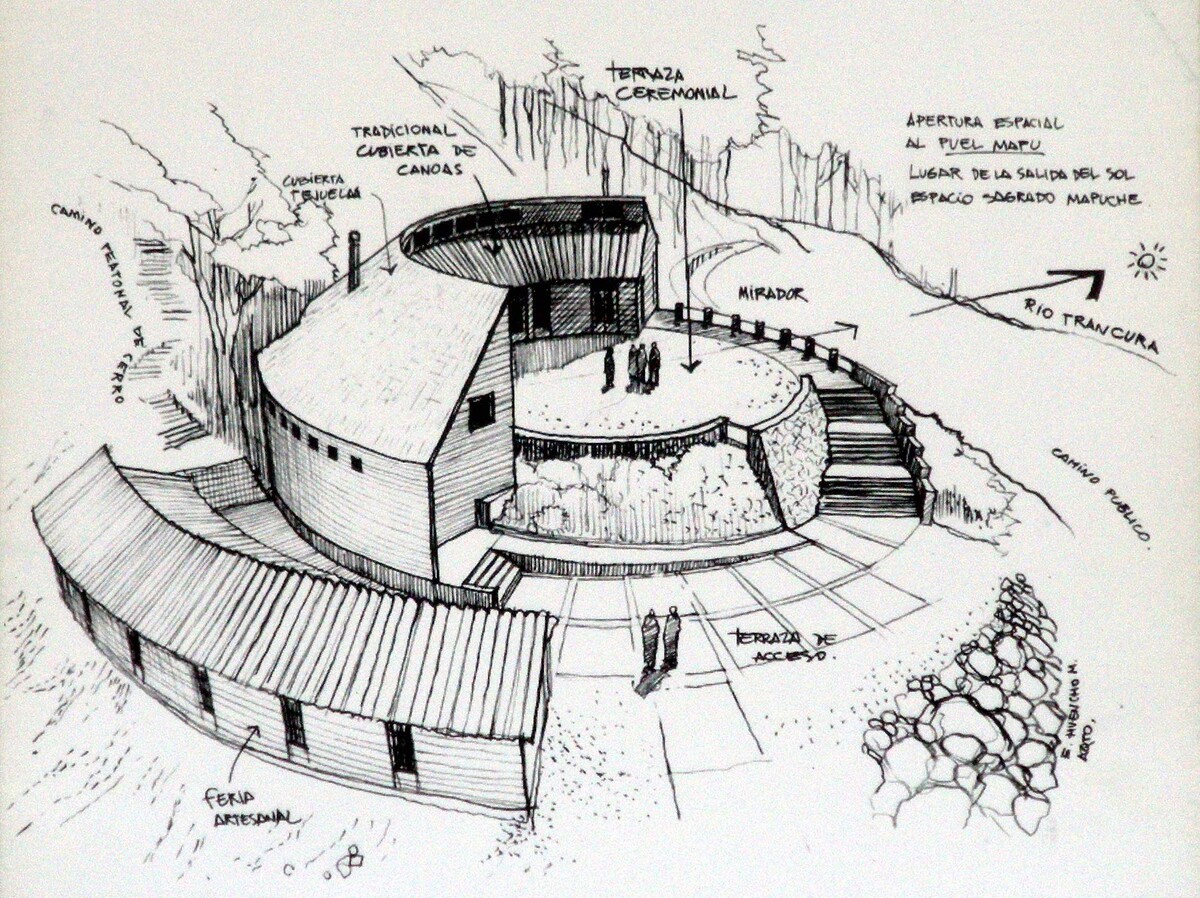

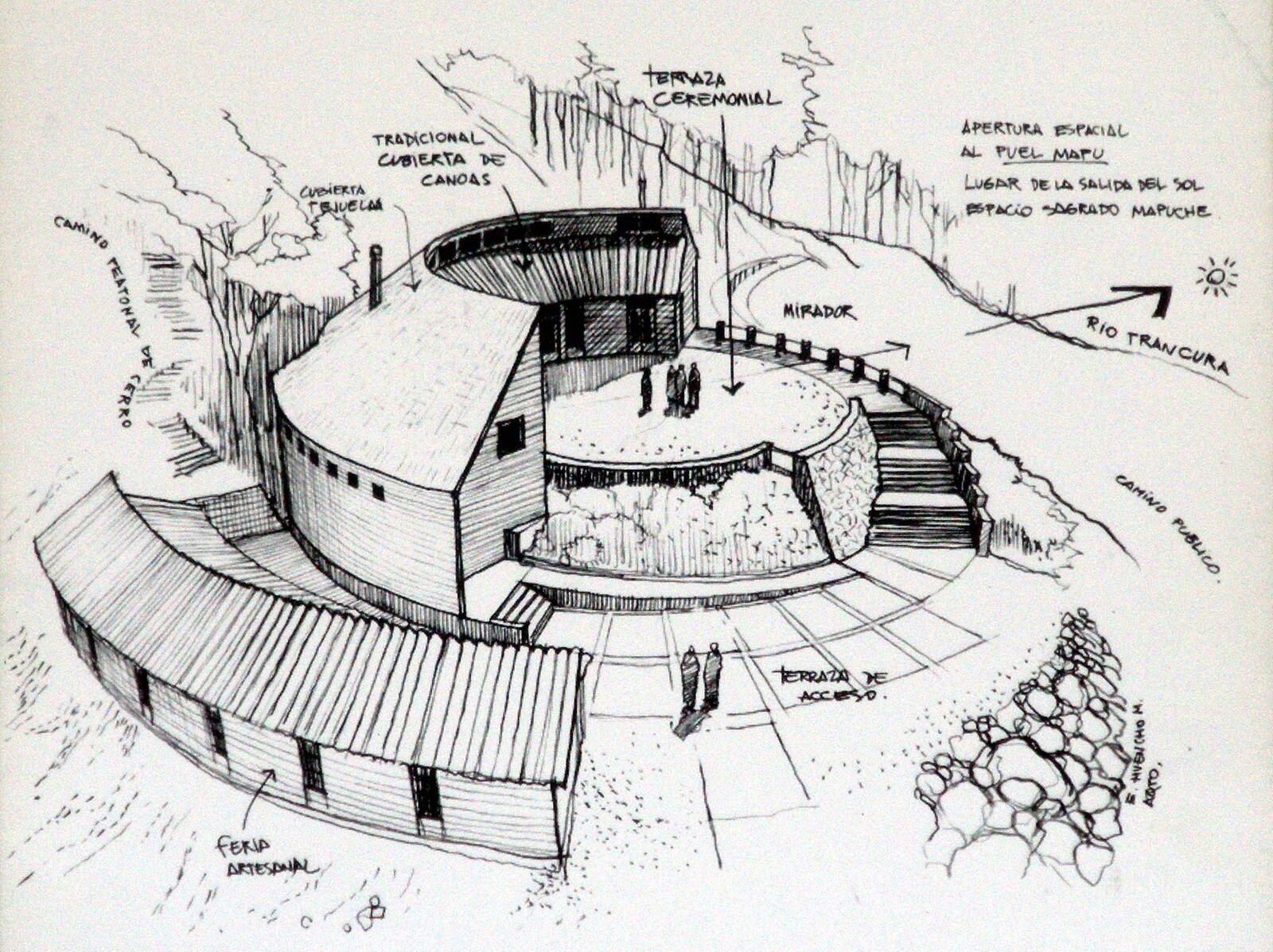

The first projects that followed the Design Guides in 2000 were developed directly by the Department of Architecture. The Guides were later incorporated by the architecture offices in charge of their design development. However, Indigenous organizations were the principal promoters of the Guides. Their graphic format provided a completely new way to communicate specific expectations or concerns for architectural projects which would otherwise be invisible to people not versed in their cultural significance, such as the Mapuche respect towards the sunrise, the presence of fire, the organic form of ancient archetypes such as the ruka (traditional home) or the ngillatuwe (ceremonial site), modes of inhabitation, specific types of spaces, symbology, and places of high spiritual meaning.

The Guides constitute a diverse repertoire of antecedents of the Mapuche and Aymara cultures, case studies for reference, and recommendations for different approaches towards architectural design, including siting, spatial organization, function, materials, symbology, etc. While revising the guides in 2016, we realized that the tendency to repeat some solutions seemed inevitable, and that some elements had been transformed into a sort of identity nomenclature. For the Polish architect Amos Rapoport, the “architecture of the folk tradition, is the direct and unself-conscious translation into physical form of a culture, its needs and values-as well as the desires, dreams, and passions of a people. It is the world view writ small, the ‘ideal’ environment of a people expressed in buildings and settlements, with no designer, artist, or architect with an ax to grind.”4 But, how much of this new experience is influenced by codes rooted in the culture of vernacular architecture, or how much can there be a “traditional” architecture that reproduces formal solutions without real indigenous participation? These concerns were formulated in the 2016 version of the Guides as four principles for a culturally pertinent architecture:

1) Interculturality, recognizing Indigenous peoples as parts of a diverse and plural society where all expressions must have equal recognition, respect, and representation.

2) Participation, promoting local development and the free exercise of rights of each community.

3) Flexibility, adapting the requirements of each case to the innumerable material and symbolic repertoire of Indigenous referents for design.

4) Complementarity, making the criteria of intercultural development a requirement in the processes of public investment.

These principles and the experience of applying the Guides led us to understand that the process of designing intercultural architecture is as important as the final result. In this sense, applying the Guides in public buildings face significant barriers. These are the result of the fact that, on the one hand, state resources are predominantly focused on the phase of execution, not in design development, while on the other, initial design phases rarely prioritize the long-term benefits and values needed to broaden the conventional scope of development. Based on the freedom of self-determination for each First Nation, space needs to be given to an Indigenous understanding of development.

Trawupeyüm Intercultural Village

Based on three case studies developed in the context of the Mapuche Architectural Design Guides, three elements must be considered in order to achieve a new public architecture with Indigenous pertinence. First, public architecture should be understood as the physical and symbolic support of human development and the social interactions that define it. That implies that public buildings play a determinant role in articulating diversity, difference, social cohesion, participation, and representation in the community where they are placed.

From 2002 to 2004, I was the project architect for the Trawupeyüm Intercultural Village in the commune of Curarrehue, located in the mountains of the Araucanía Region. Here, the Mapuche peoples constitute more than 60% of the regional population, but their presence is more associated with rural space. Conversely, urban space—and its offices of government administration, police, church, and public school—is associated with the colonization that took place in the mid-twentieth century.

Our mandate was to build an intercultural space at the heart of the commune that could encourage social encounter and the diffusion of the local Mapuche-Pewenche culture. In Mapuche “Trawupeyüm” means “where we gather.” Thanks to the organizational capacities of the local leaders (including a Mapuche mayor), the vitality of the traditional culture and its effective presence in the urban space, and the willingness of public institutions and social programs to provide logistical support to the local community, we were able to develop an architectural process that gave equal weight to Indigenous and non-Indigenous points of view.5

Access view, Trawupeyüm Intercultural Village, 2002–2004. Photo courtesy of Eliseo Huencho.

Trawupeyüm Intercultural Village, 2002–2004. Photo courtesy of Eliseo Huencho.

Trawupeyüm Intercultural Village, 2002–2004. Photo courtesy of Eliseo Huencho.

Interior wood stove at Trawupeyüm Intercultural Village, 2002–2004. Photo courtesy of Eliseo Huencho.

Trawupeyüm Intercultural Village, 2002–2004. Photo courtesy of Eliseo Huencho.

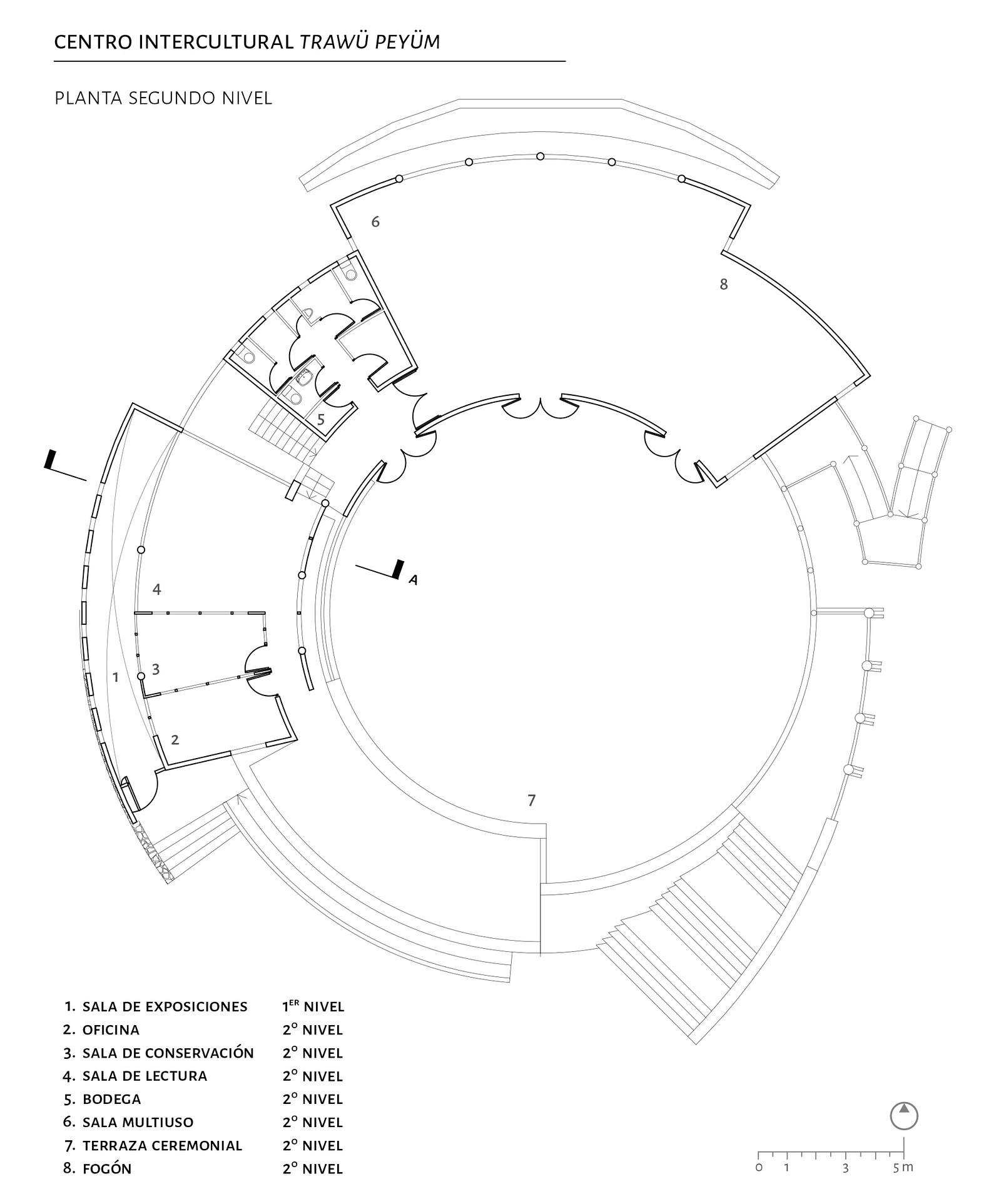

Plan of Trawupeyüm Intercultural Village, 2002–2004. Photo courtesy of Eliseo Huencho.

Access view, Trawupeyüm Intercultural Village, 2002–2004. Photo courtesy of Eliseo Huencho.

The building was defined, with active participation from the community and local technical teams, according to the activities that it would facilitate. The building—designed according to the traditional archetype of the ngillatuwe, a semicircular space open to the east—needed to create a place for the performance of ritual; it needed to host the nütram, the traditional form of conversation around a fire. Thus, there had to be a fire pit, which would also allow for the practice of traditional cooking. The building also had to include a public library with books and computers, a small museum, and a visitors hall, and it needed the capacity to accommodate social gatherings open to the whole community.

For the local peoples, it was key that the architecture related to the houses of their grandparents with a roof made of canoes, or hollowed trunks arranged as overlapping full-length roof “tiles” as in the typical mountain ruka. Thus, it was necessary to learn from the vernacular material culture about the best time of year to cut the trunks so they would not crack, to know whether they had to be sourced locally or if there was a maximum distance within which the materials would perform well, etc. In normal public works projects, such matters would simply be delegated to the contractor, or not considered at all during the construction process.

This project demonstrated the challenges of addressing Indigenous and intercultural priorities through conventional design processes. Normally, the spatial program of a public building is calculated according to a criteria of “cost-efficiency,” and fails to account for “intangible” benefits.6 In fact, public design guidelines specifically prohibit taking into consideration anything for which “there is a difficulty to quantify and/or value the benefits of the project, especially when this implies the application of value judgements.”7 Rules such as these not only normalize but reproduce cultural exclusion. Similarly, interculturality is often addressed through belated participatory processes that only affect accessory matters. Just because the Indigenous Architectural Design Guides are applied does not always mean that a project will be pertinent to Indigenous peoples. The limitations established in the phases prior to architectural design must be recognized, from the moment a location is identified to the initial conceptualization of the facilities to be provided.

Intercultural Hospital of Nueva Imperial, 2006. Courtesy of Ministerio de Obras Públicas, Dirección de Arquitectura.

Intercultural Hospital of Nueva Imperial

The second critical element for a public architecture of Indigenous relevance concerns the symbolic and effective appropriation of public space, or, the method through which a community identifies with, uses, takes care of, and defends a space as their own. For Indigenous populations, this process takes place within a continuous struggle of objecting to the conditions in which they are situated—usually far from the center and the present, reduced to the stereotypes of the farmer, the migrant, the indigent, the uncultured—and signifying new urban practices, social networks and organizations, recuperating originary values and traditions, and creating neologisms in traditional language.8 This is what took place in and through the architecture of the Intercultural Hospital of Nueva Imperial (2006), which sought to formally reflect the intersection between two medicinal systems brought together within the public system.9

Mapuche medicine room, Intercultural Hospital of Nueva Imperial, 2006. Courtesy of Ministerio de Obras Públicas, Dirección de Arquitectura.

As part of the Ministry of Public Works, and acting as an advisor to the Mapuche Coordinator and collaborator of the Ministry of Health, my participation in the phase of architectural design allowed me to witness the contradictions, limits, and opposing visions on each side, until we arrived at the best possible solution which was ultimately built. The medium-sized hospital serves 100,000 inhabitants in the coastal sector of the province of Cautín, where 53.8% of the population is Mapuche. In the “Mapuche building” there are eighteen machi (traditional doctors), two puñeñelchefe (midwives), and five ngütanchefe (bone repairers). Of the patients that seek Mapuche medicine, 60% do not belong to this originary population.

While the formality of hospital architecture predominates, the significance of family and collective participation in Mapuche medicine led to the creation of an additional built area to meet the formal and spatial requirements of Mapuche rituals. This building, a space with branches, follows the guidelines of the traditional ruka and has a rewe (altar), all oriented and open towards the sunrise. The degree of complementarity between these two medicinal systems is embodied in the construction. Here, architecture is the support and expression of social and cultural diversity and integration.

We Liwen Valdivia Home

The third required element is the contribution of public architecture to the construction of Indigenous ethnic and cultural identity. This process unfolds at the individual level based on social recognition, as strategies are learned and adopted to preserve identity in multicultural contexts. This phenomenon, observed in migrant groups, also applies to urban Indigenous populations, who often live in cities as foreigners in their own territory. In a minority context, the construction of identity involves three types of strategies: the recomposition of one’s identity, combining elements of the majority identity and their own; the denial of traits assigned by others to represent one’s own culture; and collective actions of revindication in public space.10

This phenomenon takes place in Indigenous university homes in Chile. Fifteen such homes exist in Chile, although only three were designed as such; the rest were adapted from existing buildings. Most are self-regulated and administered.11 Some homes were established as residential components of larger cultural centers, such as the We Liwen Valdivia Home (2017), one of the more recent public architecture projects developed by external consultants and designed for the development of Indigenous populations. Recommendations of the Design Guides were used as a reference for contract regulations.

The urban Indigenous reality is often conceptualized through the lens of the loss of identity, a tendency without a counterweight, especially for new generations born in cities. Within these populations, the understanding of identity has shifted away from an objective and ethical focus, centered on a set of permanent and definite characteristics, and towards a more subjective conception in which definitions arise from the individual’s self-recognition and their adherence to a social group.12 This shift in the process of identity formation could also improve our understanding of architecture’s potential.

The Valdivia Home was first initiated in 1999 when a group of students and their families organized themselves to rent a common space. Their experience speaks to the interaction of architecture and the city with Indigenous peoples. They were initially rejected—one former resident of the home describes that they were not welcome as renters. They then hid their urban presence behind the anonymity of common façades, and finally constructed a referent in public space: a new public building of 1,021 square meters housing seventy-two students and operating as a Mapuche cultural center.

Interior wood stove, We Liwen Valdivia Home, 2017. Photo courtesy of Eliseo Huencho.

Conclusions

The 2019 Longitudinal Study of Intercultural Relations shows an increase in Indigenous self-identification since 2016.13 Of the population that did not self-identify as Mapuche in 2016, 23% declared themselves as such in 2018. One factor in this increase is that in mixed families, children and non-Indigenous parents may now identify as Indigenous. The study also shows increased support among non-Indigenous population for the struggle of Indigenous peoples. Across all demographic segments, there is over 80% support for the constitutional recognition of Indigenous peoples, revealing “an enormous contradiction between what public opinion thinks and the capacity of our political system to respond even minimally to this topic.”14

While multiple factors intervene in identity processes and in critical situations of intercultural relations, public building has the responsibility and capacity to shape the identity of a people as much as their development. Although they are often granted only secondary status in analyses of the city and the territory, these buildings are fundamental components of public space. And in light of their “human scale,” they include their own variables that operate in a more intimate manner with people and communities—in their daily lives, in the sense of appropriation and belonging, as a personal support for specific activities and services, and as an element of symbolic representation of the local culture.

The language of public space can identify hierarchies, presences, and exclusions that are neither harmless nor limited to externalities (such as formal expressions or declared functions), but depend fundamentally on the nature of architecture’s generative processes. The conceptual distance between the worldviews of Indigenous peoples and those that dominate state institutions cannot be overcome with accessory, last-minute solutions in the late design phase. This distance calls for participatory exercises to take place at the genesis of public building projects, and for the systematic study and analysis of the values and benefits of interculturality, social cohesion, and the recognition of the rights of Indigenous peoples to intervene in them. These rights must be accepted as a responsibility for the articulation of diversity and the promotion of tolerance.

The Indigenous worldview challenges us to consider public architecture and public space as significant elements in our development and sense of collectivity. This takes decolonizing our forms of thinking through which we impose fictitious limitations and unreal borders, such as viewing the city as a lost space, separated from the vital totality venerated by our ancestors, or by assuming that mixing forms, spaces, mediums, and expressions inevitably results in a loss of identity. Such a predetermined originary “pure state” is always situated in the past, which only Indigenous people are obligated to uphold as a condition for being. Instead, we should recognize our capacity to make what surrounds us our own and establishing contemporary forms of relation—or, as I would say in my case, to “Mapuchize” our environment.

In the context of settlement logics and the Mapuche symbolic tradition, and independent of all forms of injustice and conflict, I believe that to be Indigenous today implies the same responsibility that the ancients understood: to be the links and makers of a relation of reciprocity with all forms of life. This is captured in the Mapuche word “itxofillmongen,” which some translations inaccurately equate to “biodiversity” or “environment,” but which really reaches beyond the biological or natural. Itxofillmongen is the idea that everything lives, that nothing is empty, that everything has power and command over itself and deserves respect.

To design and to build upon this understanding implies the double exercise of taking into account the pluri-ethnic, social, technological, economic, epistemological, environmental, and emotional complexity present in the spaces we inhabit, and at the same time, selecting the elements that can put us in tune with the forms of relation that our ancestors built for thousands of years. Such is the “mapun kimün,” the Mapuche understanding of the environment, and the relationship of the person, “che,” with said environment, in which “mapun” refers to that which is territorialized.15

Architecture has the capacity to activate channels for the continuity of that ancient understanding or knowledge. To be sure, the supports available for this exercise in contemporary architecture—materials, technology, or procedures—will be insufficient, just as they are for the translation of concepts. We must be aware of these limits in order to surpass the “contemporary reinterpretation” through which design currently deals with what it understands as the past. Instead, our designs must become processes of “contemporary regeneration” of the understandings left to us by our ancestors.

Still found in the Mapuche culture, the rukafe are specialists in the construction of dwellings; they possess, by birth and by trade, traditional construction knowledge of the materials, forms, and times in which to build a ruka. This activity of building is done collectively, applying ancient codes known and shared by the entire community. As architects, we should serve in the manner of the rukafe—integrated into the community and collaborating in order to collectively build new spaces that are able to regenerate the bond with the vital totality present in Indigenous visions.

Dirección de Arquitectura, Guías de Diseño Arquitectónico Aymara (Santiago: Ministerio de Obras Públicas, 2016); Dirección de Arquitectura, Guías de Diseño Arquitectónico Mapuche (Santiago: Ministerio de Obras Públicas, 2016), ➝.

Translation note: In the Southern Cone—Chile, Uruguay, and Argentina—the phrase used for Indigenous peoples (pueblos originarios) is “Originary peoples.” The term “First Nations” (used primarily in Canada) is the closest in English but not quite the same. The author notes the imprecisions involved in translating Indigenous concepts from Mapuche to Spanish, which is a settler language. These imprecisions are replicated in the translation to English.

Fernando Carrión and Manuel Dammert-Guardia, Derecho a la ciudad: una evocación de las trasformaciones urbana en América Latina (Lima: CLACSO, Flacso - Ecuador, IFEA, 2019), 201.

Amos Rapoport, Vivienda y Cultura (Barcelona: Gustavo Gili, 1972), 2.

Servicio País (Country Service) is a program of the Fundación Para la Superación de la Pobreza (Foundation for the Superation of Poverty), which, starting in 1994, incorporates young professionals in city halls and institutions in distant locations within Chile as a source of social transformation for isolated and impoverished rural sectors.

Cost efficiency includes a list of all the spaces included in the project and their area in square meters.

División de Evaluación Social de Inversiones, Metodología General de Preparación y Evaluación de Proyectos (Santiago: Ministerio de Desarrollo Social y Familia, 2013).

These are all collective expressions of an Indigenous epistemology that relativizes the value of truth habitually assigned to the discourse of the specialist or the institution. Rodrigo Becerra & Gabriel Llanquinao, Mapun kimün: Relaciones mapunche entre persona, tiempo y espacio (Santiago: Ocholibros, 2017), 26–38.

The brief for this project was more a result of the activism of the Mapuche health coordinator of Nueva Imperial than the intercultural advancement of the Health Service.

Isabelle Taboada-Leonetti, “Stratégies identitaires et minorités: le point de vues de sociologue,” in Stratégies identitaires, eds. Carmel Camilleri et al. (Paris: Press Universitaires de France, 1997).

Most of these homes are publicly funded, but some of them are funded by the students families, individual grants, and joint rental contracts.

Alexia Peyser, Desarrollo, Cultura e Identidad: El caso mapuche urbano en Chile. Elementos y estrategias identitarias en el discurso indígena urbano (Belgium: Université Catholique de Louvain, 2002).

Centro de Estudios Interculturales e Indígenas, Estudio Longitudinal de Relaciones Interculturales (Santiago: CIIR, 2019), ➝.

Ibid.

Becerra & Llanquinao, Mapun kimün, 15.

The Settler Colonial Present is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture and the Settler Colonial City Project, with the support of the Department of the History of Art and Taubman College of Architecture and Urban Planning at the University of Michigan.