September 3–October 9, 2011

Tom Molloy has been making pencil drawings for years, whose subjects are taken from photographs in the newspapers, pornography or official pictures of Texans executed under the death penalty. His style is painstakingly photorealist, though he refrains from the luxurious darkness of B pencils, keeping the images light and impassive, crosshatching rather than letting lines be loose and expressive. He smudges their edges in an abrasive act—perhaps to engender some dissonance in the reception of the overly-familiar images.

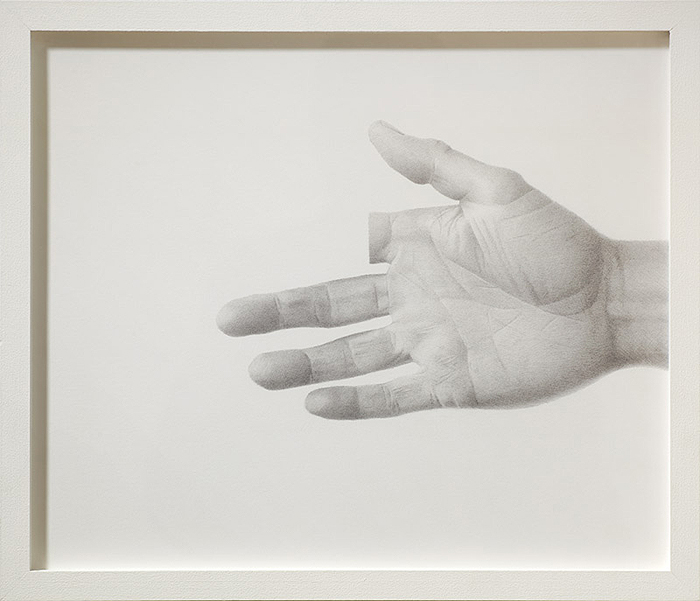

In this show at the Rubicon Gallery, however, his drawings are largely absent. The startling image on the invitation entitled Doubt (2010)—a meticulously drawn outstretched hand with its index finger weirdly truncated—is mysteriously missing from the exhibition. The image undoubtedly references Doubting Thomas’s need to put his finger in the wound of Jesus, in an act which sounds only pragmatic, but which, in the biblical context, accounts for his lack of faith. Molloy’s employment of the image, however, also suggests missing evidence, as if his finger had been excised: we are left with a dumb question and perhaps a joke at our expense.

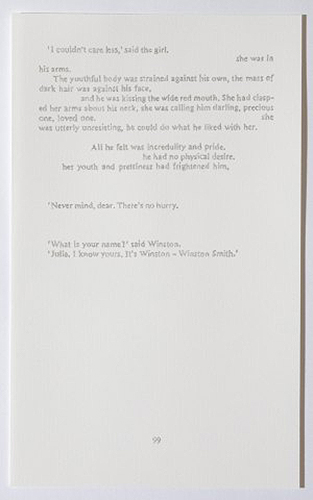

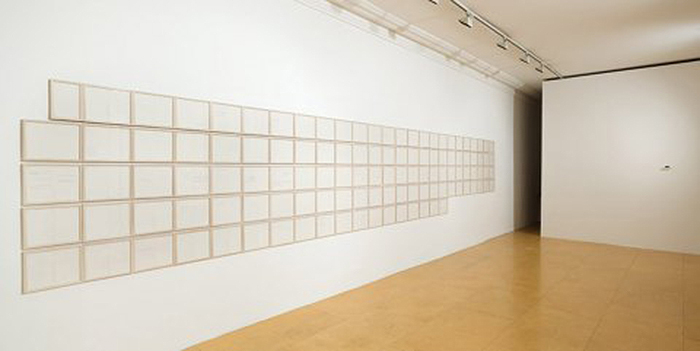

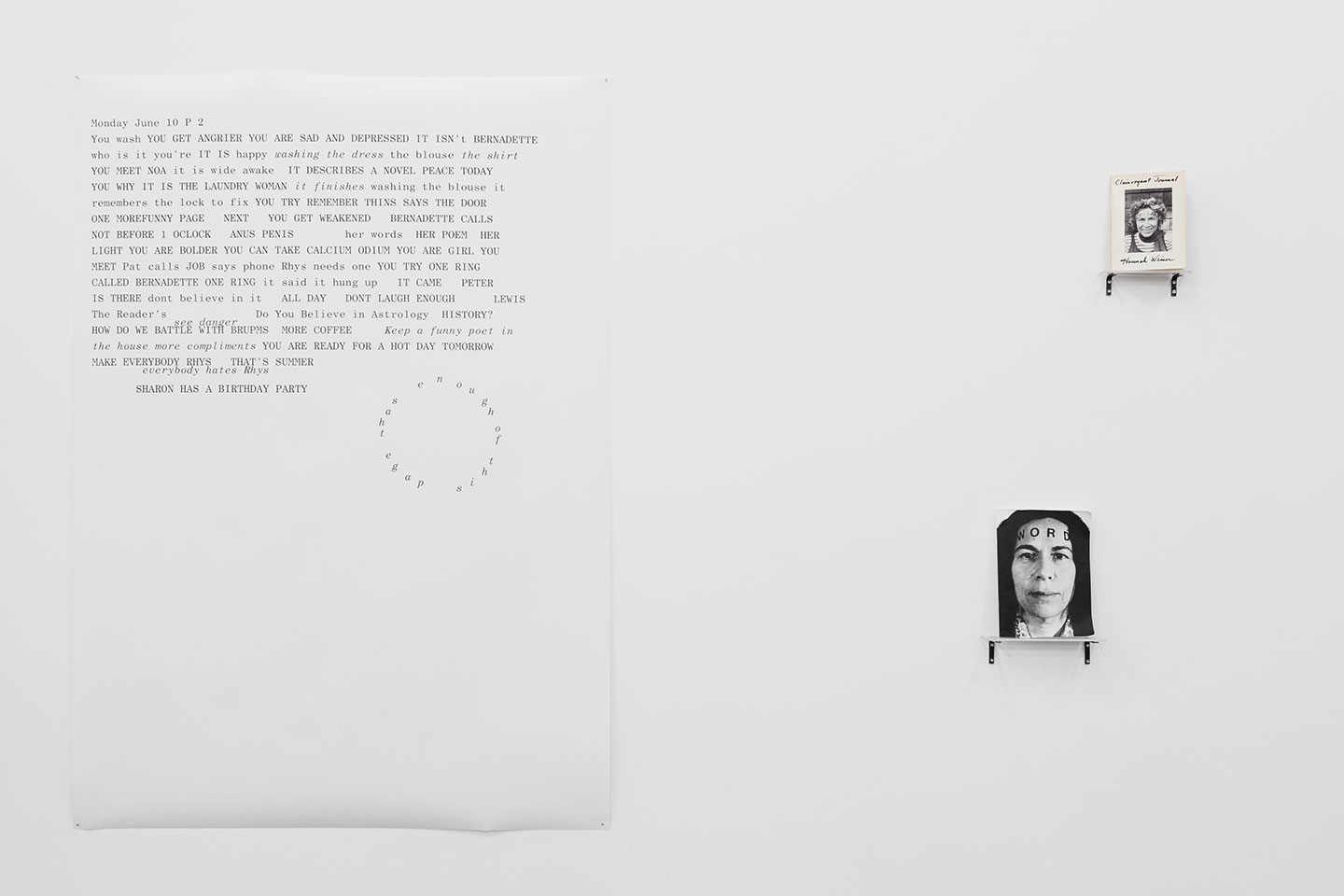

Instead of traditional drawings, the gallery is dominated by Subplot (2008), a work seen earlier in the year at the Sharjah Biennial. 219 pages of a book have been retraced in as many of the artist’s drawings, but rather than recreating the whole novel, it is a highly reduced selection of lines that pick out the narrator’s relationship with a younger, dark-haired woman. He sees her and is repelled then attracted; he engages with her, and their relationship is consummated; they attempt to remain together, and then separate on bad terms. Why and what motivates the pair, beyond commonplace attraction, is not evident; details are scant. Stripped of context, the neurotic tone is tiresome, the reasoning unclear. The protagonists here are Winston Smith, the narrator, and Julia of Orwell’s 1984; their suffocating backdrop is London under Big Brother, where independent perception, let alone thought, is not countenanced, and their affair is a primitive but potentially lethal act of rebellion. Molloy has chosen to ignore Orwell’s setting, and it’s a cruel act that punishes the already downtrodden, but in so doing he brings the quotidian into the foreground.

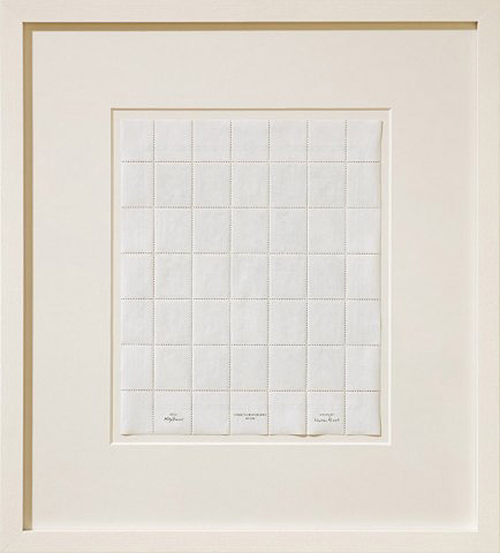

Thanks to Winston’s employment re-writing old news in Orwell’s novel, "the past was erased, the erasure was forgotten, the lie became truth"; with a nod to that, three other works in the show toy further with erasure or disappearance. Eraser (2011), is a rubber dipped in sooty, glistening graphite, holding tight the secrets of so many pencil lines. Sheet II (2009), is a page of Third Reich stamps that have been obscured by white acrylic, though not beyond recognition. What remains are the names on the margin of the printer in Vienna, the Führer’s portraitist, and the stamp designer, three figures who quite plausibly saw themselves as apolitical. And then there is Book (2011), a partially burnt book encased behind Perspex. Showing the book in his exhibition and refusing to reveal the book’s title could also be seen as a form of censorship enacted by the artist.

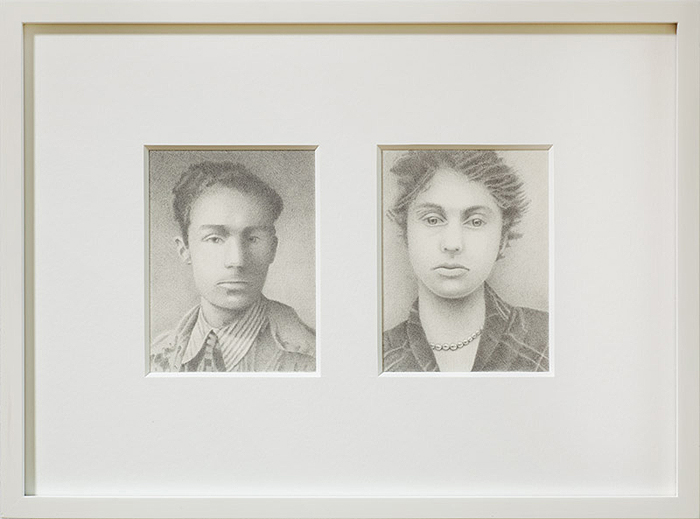

As you leave the gallery, you spot a final work in the show, Couple (2011), a double portrait of Primo Levi and Diane Arbus, who never met but lived contemporaneously and both died by their own hand. After the bleak what-might-have-beens on the margins in other pieces, this is a flourish of perhaps naïve hope. What might have been, if two people, who documented outsiders and the rejected, had indeed met.

In his previous use of familiar images, Molloy’s exhibitions directed us to think of the images’ reception, their effects and their uses, blinded, as we might have been, by our pre-formed associations. In contrast, this exhibition is largely conceptual, a set of stimuli to consider and respond to. But again it comes back to how we respond, and, here more than ever, what responsibility we bear for this response and for other daily gestures of acceptance and rejection.