March 23–May 26, 2012

Elad Lassry’s hometown exhibition on Smiley Drive, at David Kordansky’s warehouse gallery in Culver City, presents a spectrum of the artist’s rapidly diversifying practice. Most every component—from photos, to drawings, to sculptures, to architectural interventions—remains both cleverly engaged while also unreachably disjointed from each other. The overall effect is that of a nebulous exercise in plumbing the depths of the subjective acts of perception, to put it in a heady way; or rather, an exercise in looking and seeing, or indeed, the whole range of operations connecting the eye and mind that differ only by subtle, ontological measures: how a viewer places their own intents, focus, presence, while cognition takes place.

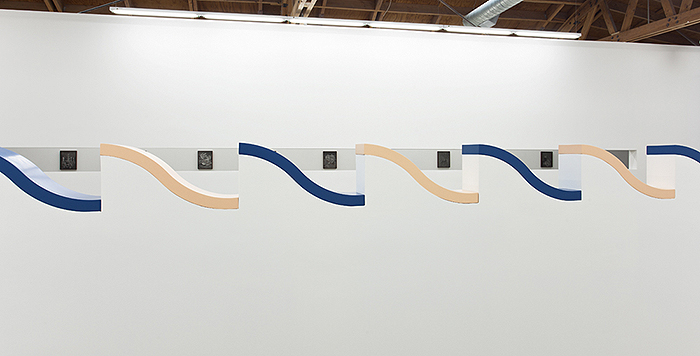

In the main gallery, there are two architectural interventions that stand out: a freestanding wall, with wave-like scallops alternating in blue and peach blocks of painted wood at chest-height. This wall runs parallel to a long rectangular aperture punched out at the same height in the wall across the room. These are the two most striking features in the show, and yet it’s unclear whether they surpass their function as framing devices, or if they should be considered artworks in their own right. This taps into a timeless philosophical debate, which, thankfully, unfolds empirically and without resolution, rather than through academic conjecture. From almost any point in the room, architecture orients what a viewer sees, and what is hung on the walls has been done so with meticulous care. As the viewer circumambulates the space, the series of drawings aligned with the sideways slit can be read laterally like a tracking shot. Similarly, the photographs “flicker” as they are hidden and revealed while walking past the undulating waves. That is, the spatial conditions Lassry has designed frustrate the presumed stillness of the images. The gallery, viewer, and artworks coalesce like a cinematic apparatus.

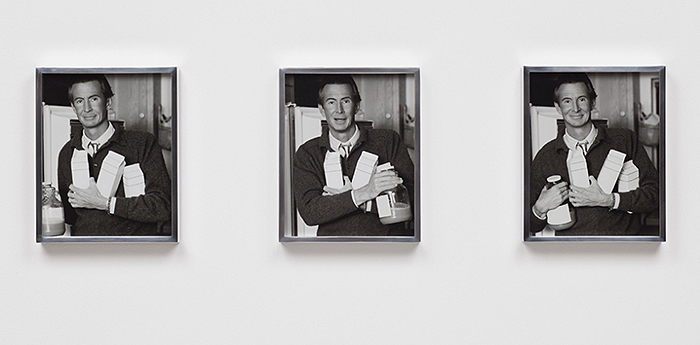

The aforementioned drawings are blithe sketches of yuletide baubles, treats, pinecones, and whatnot, a kind of analog Americana stock photography rendered in charcoal. Although they aren’t photographic, they maintain a certain “snapshot” sensibility. The actual photographs nearer to the waves are sets of staged occurrences featuring a favorite subject of Lassry’s, the actor Anthony Perkins. In one set, a triptych, Perkins handles an armful of milk cartons and juice. Lassry has retouched his face and denuded the products of their branding. The temporal distance separating each image is a mystery: they are similar enough to be individual frames taken from a momentary sequence of action, but in their polished absurdity it seems possible that this shoot dragged on for hours, days, or years. With the images’ referents to origin and narrative erased, all emphasis is placed on the very place and time occupied by the viewer. Whatever order or meaning may be interpreted from the subjects selected for the pictures of this show only serves to outline a unique cognitive experience in the gallery. That and Lassry’s ever-growing visual lexicon, which is astoundingly expressive as a language in light of its refusal to adopt an operative grammar.

The doorway to the back room is conic, imparting some kind of organic intimacy perhaps? Inside, the hanging is sparse compared to that of the main gallery. Three photographs are anchored by a peculiar sculpture in the corner. One of these pictures depicts shortbreads in a free fall, recalling vaguely the holiday drawings from the hall. The others, a curly chrome candlestick and a double-exposed squirrel-for-hire, elude rational categorization but, nonetheless, are discernable as images typical of Lassry. I don’t get the green lacquered baby bed made of upside-down and right-side-up crosses. It chafes the room with a mood that is too identifiable: iconoclastic, apparently. The look of it feels clumsy compared to the enigmatic, withholding precision of everything else in the show.