September 26–November 16, 2013

The principles of OOO—the object-oriented ontology that has emerged within the last decade—are now permeating almost every area of cultural production, structurally redefining the most fundamental relationships between things. In recognizing the agency and independence of all manner of nonhuman entities, and in proposing a system of holding things together that does not depend exclusively on human signification and representational capacities, this metaphysical movement is attempting to rebalance human and nonhuman rankings to fascinating egalitarian possibilities.

The Gravity of Things, an exhibition curated by Chris Sharp (who is, full disclosure, a regular art-agenda contributor) at Galeria Quadrado Azul, appears to be one of the most noteworthy engagements with this theoretical frame. It posits that things—all matter of things, such as an ant, a wardrobe, a leaf, or a person—are much more than a mere support of a human’s projection of meanings, intentions, or signs, and that they rather ought to be considered in light of the relations and processes that they give rise to, as well as for how they entangle matter and meaning.

The way in which things have a certain gravity that organizes, bends, and shapes the space around them is clear even before entering the exhibition. Walking across the long, narrow corridor leading into the gallery, one sees an old, cumbersome armoire floating in the air, suspended, like a magical apparition. Once inside the space, both the armoire, Mandla Reuter’s The Agreement, Vienna (2011), and the human presence rotate, as the revolution of the armoire induces the visitor to walk around it. The sculpture’s presence and its dual condition as a concrete object and as an image, clearly influences human action and thought in ways that cannot be locked into specific rational modes. The Agreement, Vienna appears as an invitation to relate to things differently, and to listen to the forms of empathy that emerge from the relationships between foreign, unknown bodies. Such invitations permeate the exhibition and the works that are sparsely dispersed within it.

On one of the walls of the gallery, Fernando Ortega’s photographic diptych Short cut I and II (2010) documents the results of the artist’s minimal gesture, which makes evident the potential repercussions of one’s unseen or unconsidered actions. Each image portrays two green leaves united by a small safety pin. Positioned in the space between the leaves, the pin becomes a privileged crossing point for an ant, which uses it as a shortcut to move faster from one place to the other. Here, the apparent (and age-old) chasm between nature and culture becomes an obsolete contraposition, as the relations between the leaves, ant, and pin are established according to their use value rather than to their specific ontology.

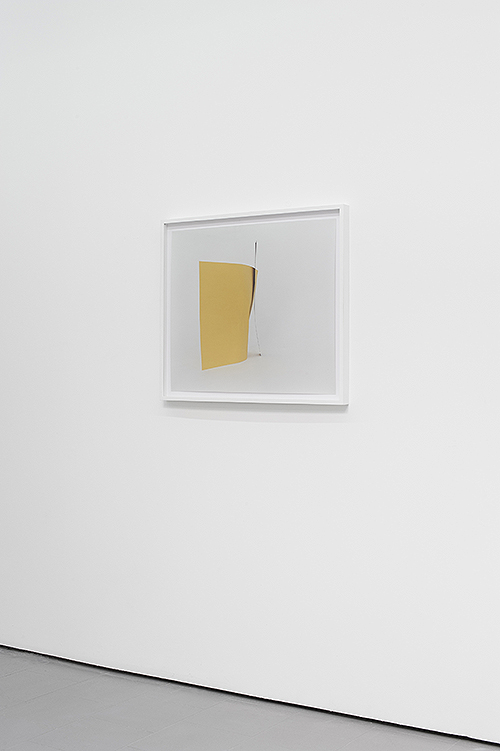

Similarly tenuous, momentary, and incorporeal is Untitled (I really must congratulate you on your attention to detail) (2012), Viola Yeşiltaç’s photographic mise en scène. Part of a larger series of similar gestures, Yeşiltaç’s photograph depicts a small sheet of bright yellow paper poised upright in precarious balance. Capturing a fleeting moment at a standstill, the work summons photography, sculpture, and performance in order to stage a delicate interplay of temporalities and functions, whereby an impermanent moment gains a fixed presence in the world of things. Floating against the large white wall that supports it, this photographed, twisted yellow square—much like Reuter’s armoire and Ortega’s bridge for an ant—upsets the laws of gravity with delightful tongue-in-cheek humor.

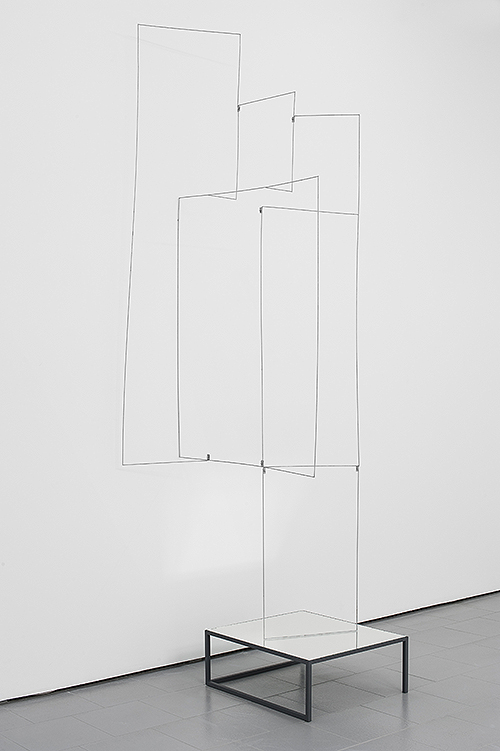

Similarly calling into question natural laws and processes, Sara Barker’s sculptural piece Nature - builder (2012) bears a title that seems to allude to Graham Harman’s assumption that “nature is not natural and can never be naturalized.”1 It is made of an arrangement of tall, pared-down metal rods whose verticality is on the verge of collapsing. Lying on a mirror plinth, and apparently freestanding, the delicate construction defines a series of quadrangular forms that, due to the slenderness of the metallic filaments that constitute them, resemble a three-dimensional drawing. Nature - builder presents itself as a feeble architectonic venture: a spatial entity that is too ambitious to sustain its own weight and requires an additional support in order to remain upright. For that reason, it extends itself into the gallery’s interiors, appropriating the adjoining wall and thus establishing a closer relation to the space that hosts it.

While embedded in their own particular ideologies and idiosyncrasies, in combination these four pieces launch the foundations for a possible new treatise on gravity, one that is not based on the laws of physics, nor on the solemn matters brought about by language, but that presents itself as an invitation to take both human and nonhuman agencies into account as elements that shape and determine social space and modes of existence.

Graham Harman, Guerrilla Metaphysics: Phenomenology and the Carpentry of Things, (Chicago: Open Court, 2005), 251.