September 7–October 19, 2013

Positioned like sentries on either side of the North Sea as it collides with the Atlantic Ocean, Norway and Scotland have long been held under the sway of this most frigid body of water. Crane-filled shipyards, woolen fisherman’s sweaters, mythical horned Viking helmets, and—as the exhibition “Sea Salt and Cross Passes” emphasizes—billowing canvas sails underpin both the mythic romance and gritty realities of these two nations. In her new memoir, The Faraway Nearby, writer Rebecca Solnit remarks that walking “into an exhibition can be like walking into the middle of a conversation that doesn’t make sense unless you know who’s talking and what was said earlier.”1 This is certainly true of this exhibition, which marks the first half of an exchange between two galleries, STANDARD (OSLO) and Glasgow’s The Modern Institute, and takes as its starting point the stretch of water that separates the two countries and informs both their cultures. The image of sails, so often captured in the maritime paintings that proliferate in seafaring nations, is what opens the exhibition’s conversation—and in particular, the diagonally sketched lines of masts attached to ships yawing off-center.

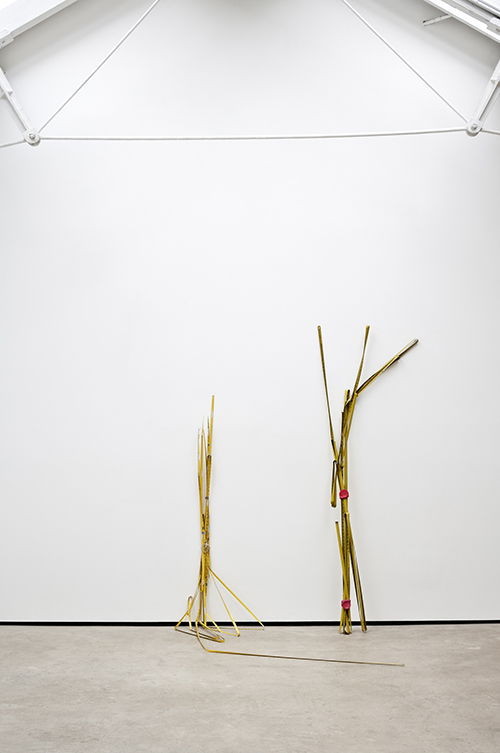

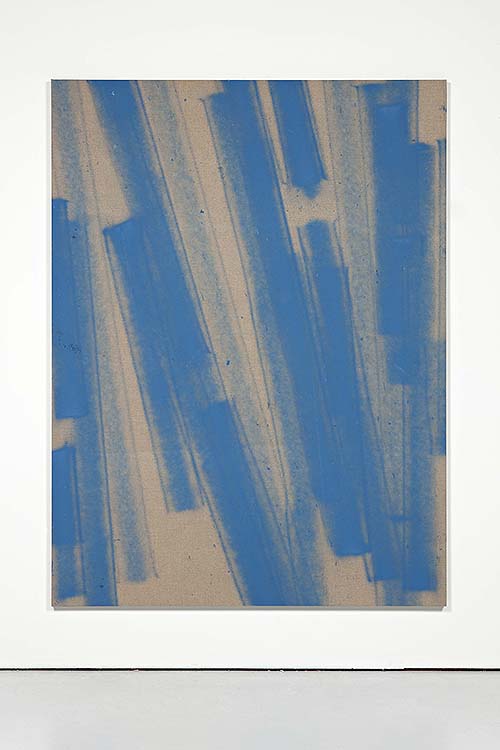

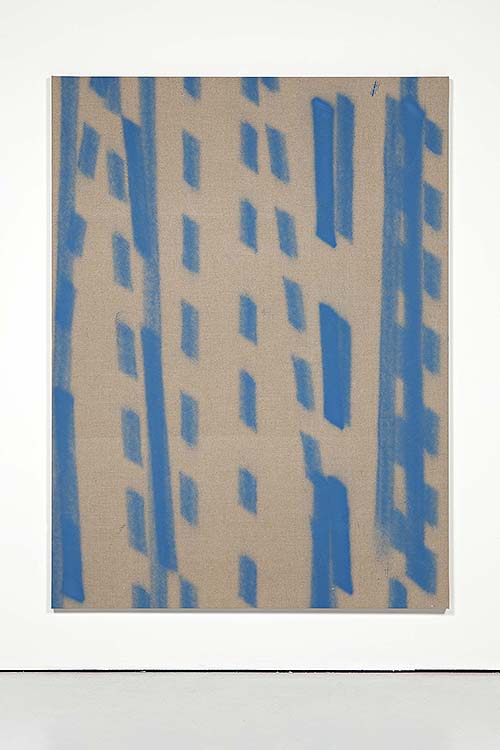

With its depiction of not only one, but three diagonal masts, Losbåten “Arendal 2”—an undated work by the late-eighteenth-century painter Martin Aagaard—exemplifies the genre (and is framed by gilt rope and sand, no less). Hung directly across from the gallery entrance, it serves as an historical and aesthetic anchor, drawing STANDARD’s selection of recent works into an artistic tradition easily reduced to flea market kitsch. The contemporary artists’ overwhelming use of industrial materials—aluminum, wood, steel, leather, concrete—splits open the working-class reality glossed over in Aagaard’s pleasant oil, as with Matias Faldbakken’s Untitled (Ladder Pull) (2013), which looks like a rigging accident in progress, its two massive concrete blocks just beginning to crash into the shipping pallet below. Strung up on brightly colored straps, the full weight of the blocks hangs off an extension ladder tucked into the rafters, its aluminum contorted and twisted, threatening to shear apart. Chadwick Rantanen’s Untitled (yellow/clear) and Untitled (yellow/pink) (both 2013), two metal measuring tapes pulled from their plastic containers like unspooled cassettes, also reflect the image of industry crumpled under unapologetic force. They lean precariously against the wall, as useless and fragile as shattered masts, all the more dynamic than the “whimsical” painted versions that the gallerists cite as being essential to the exhibition’s curatorial framework. Indeed, even works like Fredrik Værslev’s “Trolley Painting Series” (2012), consisting of wide strips of blue spray paint cutting across four large-scale, vertical tan canvases, create a healthy abundance of that key diagonal line.

Although my visit was no doubt aided by the dreary pall of drizzly mist (or “dreich,” as the Scots would say) clouding the gallery’s vaulted glass ceiling, the hard, cold, isolating atmosphere that pervades “Sea Salt and Cross Passes” arises from trading the moody romance associated with Aagaard’s depiction of fishing and sailing life for the hard-edged modern incarnation of the North Sea, a hotbed of freight shipping and oil extraction. It is hardly the subject matter for decorating a hotel room wall. In fact, a photograph of a young, blond, presumably Norwegian girl, draped in an oversized striped sailor’s shirt, climbing a sunbathed outcropping of rock represents the exhibition’s only moment of overt “charm.” Yet Torbjørn Rødland’s Rock and Stripes (2001–13), like Fiona Tan’s water- and memory-obsessed film Rise and Fall (2009), invites the viewer to guess at a maudlin narrative (absentee sailor father?) of isolation and lost connections.

The exhibition’s most perplexing inclusion—Oscar Tuazon’s Untitled (2013), a tree stump captured in a metal scaffold, and the two-legged-yet-somehow-upright Corner Chair (2012), which a hidden metal bracket anchors to the wall, as a craning neck reveals—offers a sort of dissonant summary of the exhibition. Scotland and Norway’s long history with the North Sea, inextricably threaded through the two countries’ myths, culture, and livelihood, still does not make the icy waters a trustworthy bedfellow. It is at once beautiful, terrifying, and sublime, both progenitor of bedtime stories and fearsome capsizer of boats and oilrigs. Like Tuazon’s works, the sprawling expanse of water between Norway and Scotland is simultaneously wild nature overtaken by human design (like the metal creatures that strip its sea beds) and an obvious and precarious illusion of forced stabilization. Despite its wall anchor, who could trust Tuazon’s two-legged chair—or the temperamental North Sea? Though “Sea Salt and Cross Passes” takes as its anchor the formal qualities of a whimsically painted diagonal mast, it is the influence of the North Sea itself that dominates—as per usual, as the inhabitants of Scotland and Norway very well know.

Rebecca Solnit, The Faraway Nearby (London: Granta, 2013), 192.