When musician David Byrne manically repeats the line “same as it ever was,” it fails to bring pleasant thoughts to mind. To say these same words about this year’s VIENNAFAIR, however, is to acknowledge the value in returning to a pre-existing order. Last year, the fair was a strange hybrid of the VIENNAFAIR and Art Moscow; with a keen interest in boosting revenue, Russian investor Sergey Skatershikov had hurriedly appointed two new artistic directors for the 2012 edition, one of whom also helmed Art Moscow. But now the annual showcase is back in form, and again under new ownership—Skatershikov’s former partner and real estate developer Dmitry Aksenov is now in charge. The familiar combination of Viennese establishment and lesser-known Eastern and Central European figures has returned, along with a mixed bag of all sorts.

Despite these recent changes in direction, VIENNAFAIR is still primarily a European affair. Among the 127 participants, only one and a half exhibitors are from the United States: Marc Jancou Contemporary from New York/Geneva and debutant Steve Turner Contemporary from Los Angeles, who paired Maria Anwander’s erased art magazines with Pablo Rasgado’s assemblages of painted drywall. The only East Asian participant is South Korea’s Gallery H.A.N., with a range of work from Myungil Lee’s neon color abstractions to Kyung-Ja Rhee’s calm calligraphy-style ink paintings on offer. Compared to all the fuss around Russian galleries last year, when its collectors were declared VIENNAFAIR’s hope and future, things have significantly calmed down. However, Russian representation is still quite strong with eleven participants, among them pop/off/art Moscow-Berlin and Triumph Gallery. Regina, one of Moscow’s remaining big players (which also has a requisite outpost in London), even dared to critique the market with the artist-duo EliKuka’s Corrupt Performance (2013), which sold art by the meter.

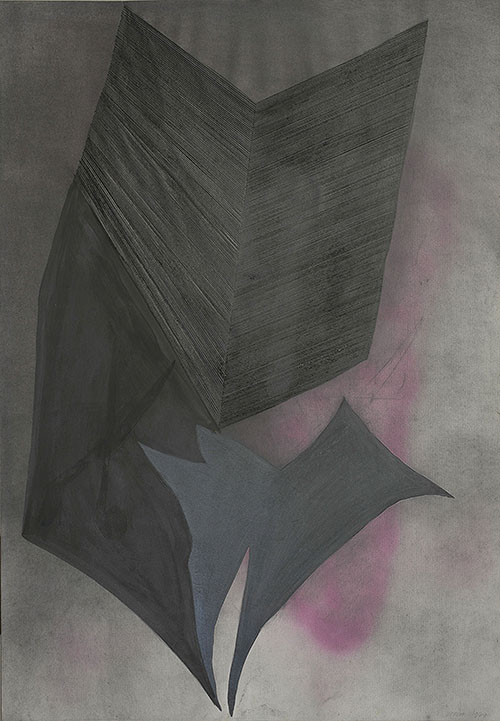

The Austrian dealers also remain loyal participants. Galerie Lisi Hämmerle from Bregenz benefited from “Zone1,” a section of the fair for the promotion of young talent sponsored by the Austrian Federal Ministry of Education, Art and Culture, where she presented the artist-duo Albért Bernàrd’s curate-as-you-go-by booth, which allowed their works to be hung at will. Gabriele Senn Galerie launched a solo installation of Kerstin von Gabain’s prosthetic furniture; Galerie Andreas Huber invited visitors behind Carola Dertnig’s Curtain (2012/13) that metaphorically transformed the booth into a stage; Galerie nächst St. Stephan Rosemarie Schwärzwalder combined Ernst Caramelle, Herbert Brandl, Michał Budny, and Heinrich Dunst into a reflection on pictorial, illusionistic, and conceptual space. Charim Galerie, Galerie Georg Kargl, and Galerie Krinzinger offered a cross-section of work from their programs. Krinzinger’s black and white corner—collages by Goran Petercol and paintings by Franz Graf—confirmed a penchant for color reduction among the Viennese galleries, not to mention Galerie Krobath’s booth devoted to Esther Stocker’s black-and-white patterned sculptures, and Galerie Hubert Winter’s presentation of Franz Vana’s “Black Series” (1974–78) consisting of greyish graphite drawings (a discovery that won Winter his third consecutive prize for best booth by an established gallery).

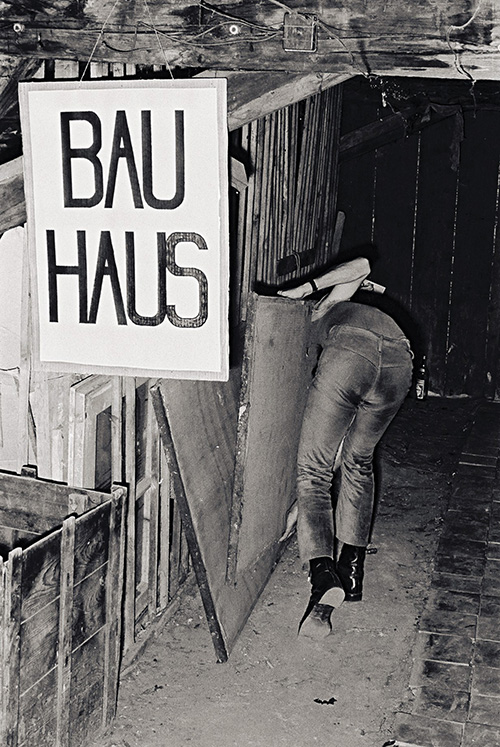

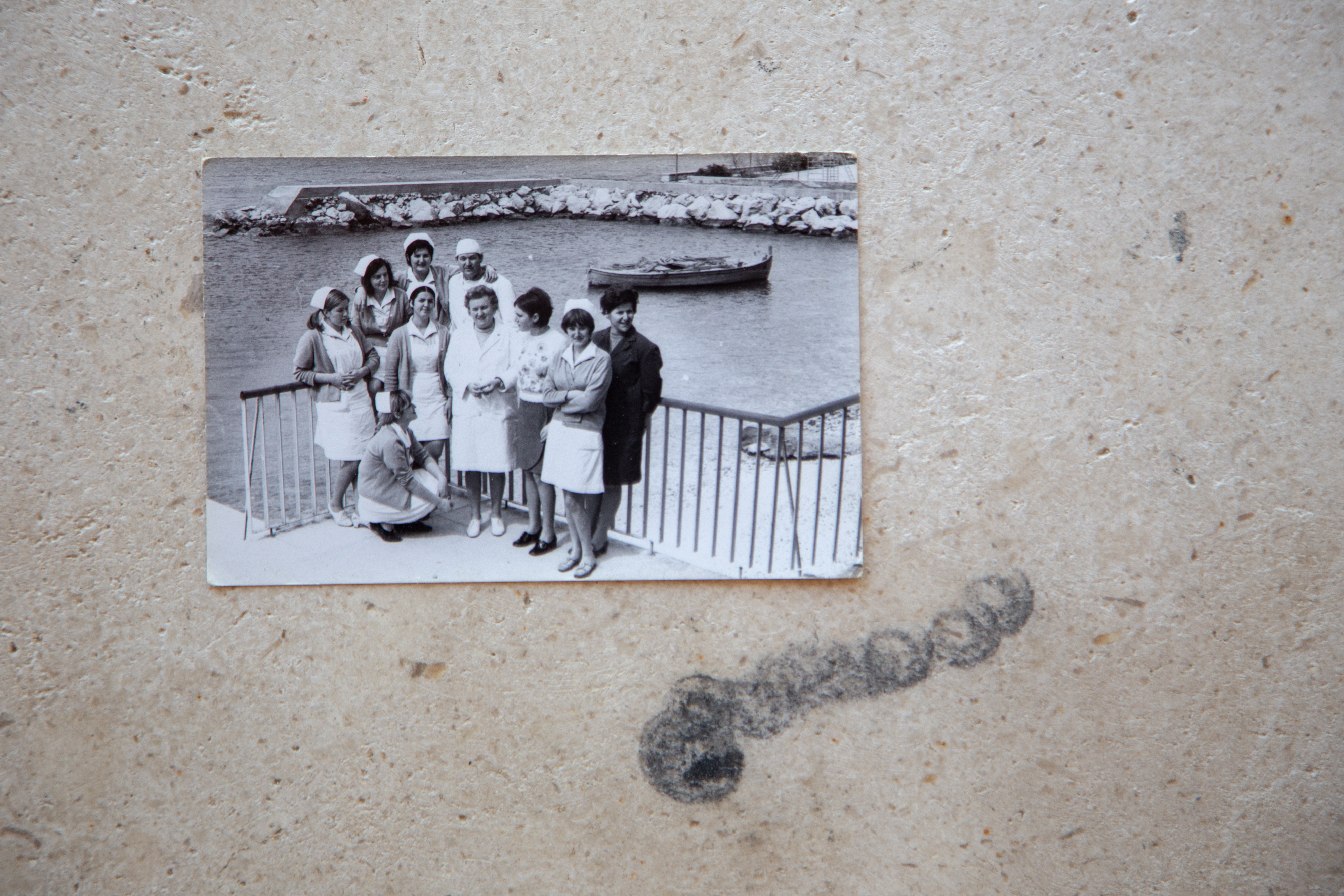

If it’s new (but not necessarily just-out-of-art-school) discoveries that you are after, this is your fair—especially if you are on the hunt for Central and Eastern European Conceptual art from the 1970s. Berlin’s ŻAK | BRANICKA featured Mostar-born Radomir Damnjanović Damnjan’s white-paint-on-raw-canvas text painting entitled Misinformation: Red and Blue (1972); Warsaw’s lokal_30 showcased the feminist performance artist Natalia LL’s luscious photographic series Post Consumer Art (1975). Galerija P74 from Ljubljana introduced Bálint Szombathy’s laconic “Bauhaus Series” (1972), consisting of photographs of the artist’s modest dwelling with a simple “Bauhaus” sign standing in for the design aesthetic’s obvious absence; and Jecza Gallery from Timişoara presented the work of the artist group sigma 1 (active 1969–80)—self-declared mediators between science and nature who were tolerated by the Romanian regime despite their clear departure from Socialist Realism.

Romania was also featured in the VIENNAFAIR’s “Diyalog” special projects section, which offered the country a platform for its young galleries and nonprofit spaces. Bucharest’s Club Electroputere unveiled the peculiar photographs of artist Mihail Trifan and his sisters grimacing and juggling with all sorts of food, while Salonul de Proiecte curated a group show about money, which included Marina Albu’s letter pleading for money to, “Please, please come back to me!” This sentiment might have echoed some of the concerns surrounding the VIENNAFAIR that are yet to be sorted out. One question in particular regards what will happen to former fair owner Skatershikov’s initiative for an acquisition fund; it has (at least temporarily) been suspended.

The new owner Aksenov has promised a long-term engagement with VIENNAFAIR, and he and his directors, Vita Zaman and Christina Steinbrecher-Pfandt, will certainly have to think long term, since the fair’s strength is that it offers quite a bit of art that is aesthetically strong but not necessarily an easy sell. At the same time, the Austrian dealers, the fair’s commercial backbone, need to be happy, too. Before the Russian takeover, the fair, a “nonprofit enterprise”—as the manager of Reed Exhibitions Messe Wien admitted in 2011—was seen as a politically vital conduit between East and West. Now, it simply needs to generate a profit. Zaman and Steinbrecher-Pfandt have managed to make the fair look good, but now they will have to work on the formation of a new collector base, and open up the minds of those who are willing to spend their money but might need a little guidance in doing so. A small undertaking like VIENNAFAIR probably only stands a chance if it manages to differentiate itself from the other, more powerful European fairs, focusing on its “Unique Selling Point” (to rely on a bit of city-marketing speak) and local market conditions. In doing so, let’s hope it doesn’t shy away from showcasing the somewhat more, wonderfully, difficult stuff.

Outside of VIENNAFAIR’s four walls, curated by_vienna 2013, now in its fifth year, spotlights the gallery scene throughout the city. For each edition, about twenty participating galleries present special guest-curated group exhibitions under the banner of a collective theme. Opening up one’s gallery to non-gallery-program artists and curatorial experiments, especially during the peak season that is VIENNAFAIR time, is a generous, even audacious gesture, but this risk-taking is shored up by municipal investment: curated_by is initiated and financed by Departure, the city of Vienna’s so-called creative agency.

This year, curated by_ confronted viewers with the rather tedious question “Why Painting Now?” “Why not?,” you may be tempted to shrug back, tired of the repeated, often invasive check-ups on painting’s vital signs and status. That said, a question is always better than an “and-that’s-that!”-style exclamation (“Painting Forever!” was recently served up as the motto of the Berlin Art Week). And while you couldn’t be too sure that some of Berlin’s participating institutions believed in the statement they had subscribed to, many of the “Why Painting Now?”-affiliated curators manifested what looked like a credible interest in their subject matter.

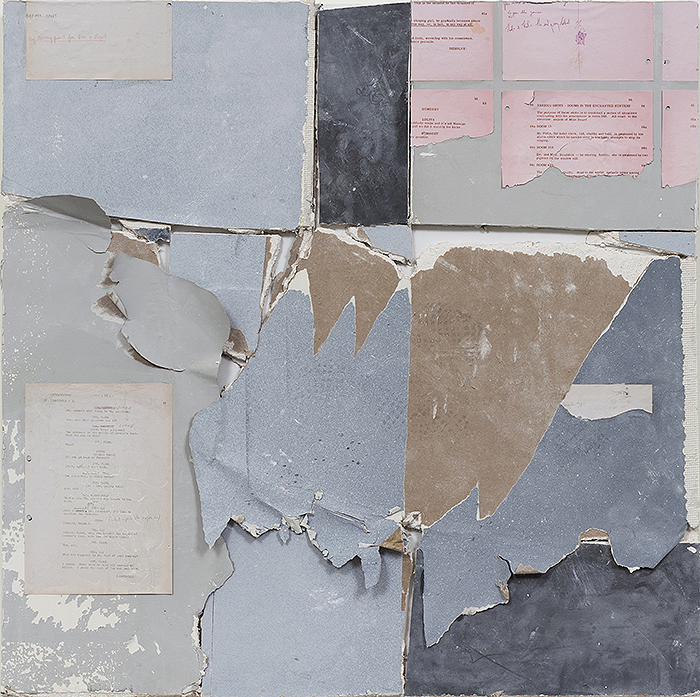

Franklin Melendez set up a “Dress Rehearsal” (at Galerie Andreas Huber), calling up painting’s conventions and props. Artist Liam Everett’s wooden panels, for instance, came in the guise of abstract gestures, but are the result of a process of removing acrylic paint with acid. And Nick Dash’s empty, screen-like wooden supports almost beg to be covered, to have something projected onto them. At Galerie Emanuel Layr, curator Bart van der Heide departed from a seventeenth-century trompe l’oeil painting of a canvas’s back and ventured into an exploration of how and under which conditions art, or painting, is being produced today. He brought together, among others, one of Anna Oppermann’s mise-en-abyme-like pieces with Christopher Williams’s reflections on photography, and a number of painting-as-a-daily-routine concept canvases by Manuela Gernedel, Morag Keil, and Fiona Mackay.

Certainly another highlight was Berlin-based critic Jan Verwoert’s “next to perplexed you” at Galerie Martin Janda. His show was sparked by Vanessa Bell’s cover designs for her sister Virginia Woolf’s books. From there, Verwoert looked at the notion of adjacency, or collaboration, as was displayed in the captivating story-poems by Sarah Forrest and Virginia Hutchison, based on a series of objects the artists exchanged. A lot of this exhibition drew from a softer history of modernism and a softer version of painting, one that envelops and embraces craft and patterning, as did Lucy Stein’s bright and colorful glazed bisque tiles, and Malin Gabriella Nordin’s playing cards or sculptures resembling slabs of marble and glittery, sliced-open geodes. I would love to see this show in Berlin, in response to the Neue Nationalgalerie’s “Painting Forever!” parade of tough, all-male painters. As Verwoert has it, soft edge is hard core. Soft edge is smart, I’d like to add.