On Fabio Sargentini’s website, the heading “gallerista regista scrittore” (gallerist, director, writer) appears directly under his name.1 While this text is dedicated only to the first of the above-mentioned professions, it will also consider the very peculiar nature of Sargentini’s various activities through almost half a century. A multifaceted figure, Sargentini (born in 1939) was, and still is, a gallerist with a peculiar sensibility towards time-based forms of artistic languages: a gallerist-curator extremely sensitive to the use of the exhibition space as a linguistic medium, and a gallerist-artist with intellectual and creative ambitions of his own. These different approaches have been fulfilled through his activity as owner of the gallery L’Attico. For Sargentini, in fact, the medium of the gallery became the primary tool for his own creative output; at first as the author of artistic and performative gestures and later in his life—and to this day—as a writer and director of theater plays.

There are at least two reasons why I would choose to translate the Italian gallerista as “gallerist.” Firstly, Sargentini had, and still has, very little of the art dealer in him—that is, someone who is primarily concerned with the strategic promotion and economic support of his artists. Secondly, the word gallerist emphasizes the relation to the space or the context where this activity takes place. Sargentini’s practice, if you will—which had particular consistency and precision during the years between 1966 and 1977—has been marked by an acute understanding of the relationship between the art produced and the place where it is exposed to the public, and by a continuous questioning and extending of its parameters. Through the history of L’Attico, we can read the evolution of the space during a crucial moment in time, and thus understand how its unique format, character, and dimensions reflected changes in art production as well as in society at large.

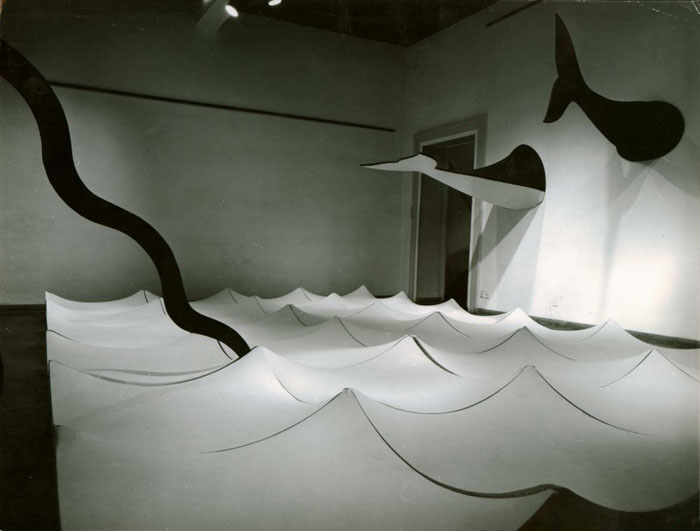

L’Attico was, in fact, opened by Bruno Sargentini, Fabio’s father, in 1957 in Rome and was devoted to Italian and international Art Informel. After a brief period of coexistence between the two, the son broke off and developed his own career with a show that would later be understood as a crucial turning point. From October to December 1966, Pino Pascali exhibited a series of sculptural works in a two-part exhibition. In particular Il Mare [The Sea]—a large installation reproducing a wavy sea with the use of white fabric—presented a key moment for the young Sargentini to question the limitations of the gallery space. Inherited from his father, this was an old bourgeois apartment located on the iconic and touristy Piazza di Spagna. The size of Pascali’s installation, hardly fitting inside the room of the gallery, obliged visitors to walk around its perimeter, almost scraping the walls. Il Mare made the space of his gallery look inadequate for such work, and suggested to Sargentini a different typology of venue where the new expressions of art could be more aptly presented. It was becoming increasingly evident that a new generation of artists, both in Italy and abroad, was breaking dramatically with the conventions of sculpture and painting and shifting to a type of art that invaded the exhibition space in a new form of communion with the environment and the visitor. Minimalism, Anti-Form, Land Art, and, slightly later, Arte Povera, as well as time-based practices like performance and site-specific interventions, were drastically expanding and challenging the borders of the spaces where art was presented and consequently impacting how viewers encountered these works.

It is not a stretch to claim that Sargentini was one of the first gallerists in Europe to both grasp and understand the consequences of these cultural shifts, and the potentialities of artists like Jannis Kounellis and Pascali, who he “stole” from La Tartaruga, another important gallery in Rome during that period. If Pascali’s sea was still indebted to Minimal and Pop language, the introduction of natural elements within the format of painting and sculpture by Kounellis marked a more organic presence within the exhibition space. In his 1967 exhibition, living birds were kept in a series of cages constituting the painting’s frame, while lines of cacti planted in the ground became the main material for his floor installation. In June of the same year, the group show “Fuoco Immagine Acqua Terra” [Fire, Image, Water, Earth], including Turinese artists Piero Gilardi and Michelangelo Pistoletto, alongside Kounellis and Pascali, turned natural and primordial elements into manifest artistic materials even before the canonical theorization advanced by curator Germano Celant under the Arte Povera label in the successive months.2

Sargentini’s work on that exhibition—though influential—only proved that his engagement with the expanded field of installation and environment was not to be limited to an organic form of language typical of proto-Arte Povera expressions, but quickly extended to more participatory and immersive formats such as the kinetic and programmatic art of Gianni Colombo (who installed his iconic work Spazio Elastico at L’Attico in January 1968), or the post-minimal forms that Eliseo Mattiacci presented in May 1968. Indeed, these new artistic developments also required a more direct and physical participation on the part of the spectator, and were surely a reflection of the wider social and political changes of the 1968 movements. In this context, the format of the bourgeois apartment as the place to exhibit art became increasingly anachronistic.

A decisive step towards a new conception of the exhibition space occurred in the meeting that Sargentini had in Rome with Italian-American dancer Simone Forti soon after Pascali’s sudden and tragic death in a motorcycle accident in September 1968. Forti, a former pupil of Anna Halprin in the US, introduced Sargentini to the latest developments of the New York music and dance scene, which he went on to champion with enthusiastic dedication for many years to come. Her exhibition “Danze costruzioni” [Dance Constructions], hosted in the original gallery space on Piazza di Spagna, is considered to be the first performance to take place in a European gallery. During the first of a two-day event, Forti presented a series of four actions (from 1961–68), using tools such as ropes and inclined planes to encourage the physical and participatory activity of the spectators.

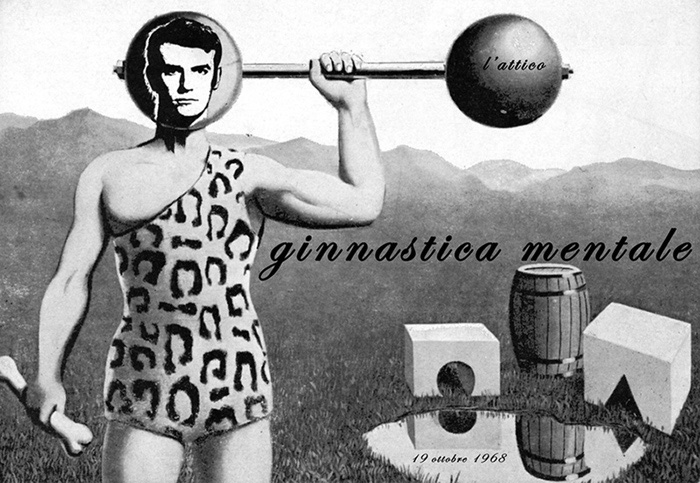

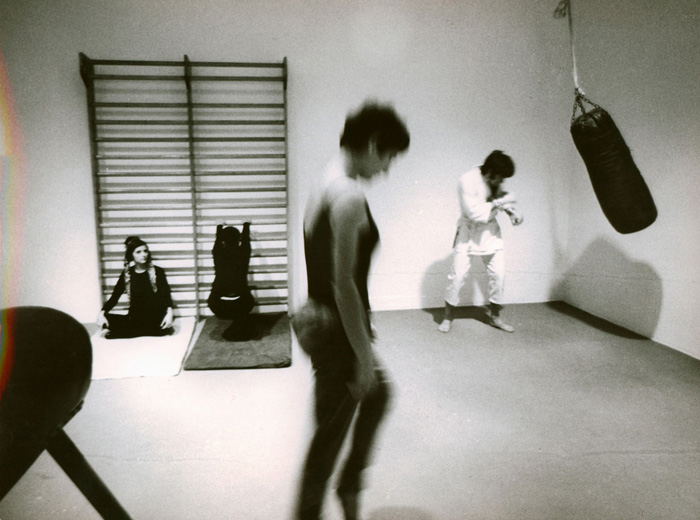

Sargentini demonstrated an immediate affinity with Forti’s approach when, in the first in a series of “authorial” gestures, he invited people to use the gallery as a gym for one evening on October 19, 1968 (a few days before Forti’s exhibition).3 In “Ginnastica mentale” [Mental Gymnastics], the institution of the gallery was demystified by its very owner while, with the two-day program of electronic music and a performance by Forti, Sargentini indicated new directions for a reconceptualized form of the gallery as a space dedicated mostly to ephemeral and time-based events. In a rather self-reflective operation, the gallery became the subject and the content of the art itself, while on the other hand, it changed its nature from a space of contemplation to a space of action, from an apparatus for the eye to one for the body. These two complementary directions marked the activity of L’Attico in the coming years.

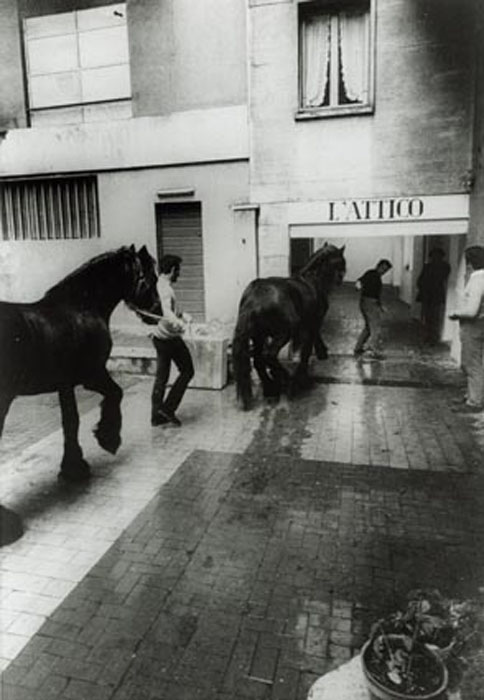

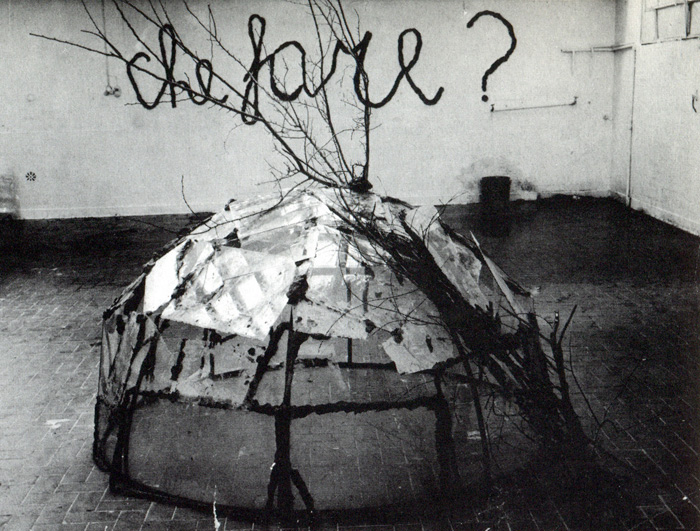

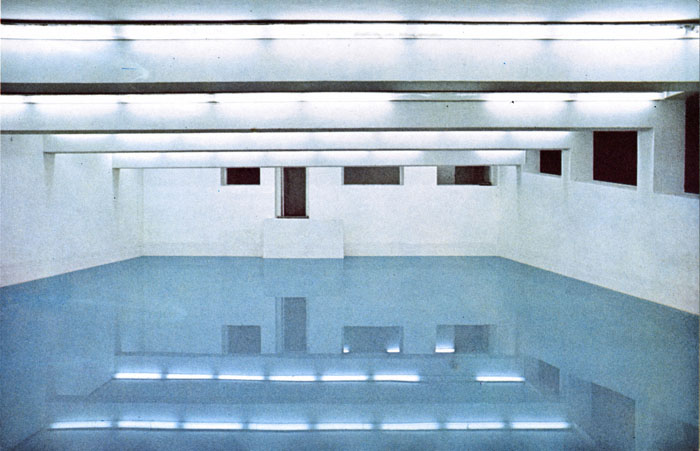

The quest for a different typology of exhibition space, already sensed as necessary after Pascali’s installation in 1966, was finally fulfilled when Sargentini found a former garage located on the Via Beccaria in Rome. If the opening of the new location took place (for highly symbolic reasons) during 1968, the first exhibition was to be an absolute landmark that helped L’Attico acquire international status: Kounellis brought in twelve live horses to inhabit the gallery space for a few days in January 1969. In the intervening years, bodies, movements, and activities of all different kinds were to follow the equine parade through the garage’s doors. Even if it was a challenging venue, extremely problematic for traditional formats but ideal for performative operations and musical events, many artists were able to realize memorable installations, turning such limitations into opportunities. On the one hand, L’Attico became the stage for extremely physical gestures: Mario Merz created an environment combining different elements such as his own car, previously used to travel from Turin to Rome, and one of his earliest and most politically charged igloos; while Mattiacci entered the gallery driving a construction roller, forming a path made of earth. On the other hand, the garage hosted art works of a more conceptual nature, even some that were on the verge of disappearance: a very young Gino De Dominicis had his first solo exhibition presenting his Oggetti invisibili [Invisible Objects], and Sol Lewitt debuted in Italy with a series of wall drawings barely visible in the vast space. It is hard to believe that all this (and more) happened in the course of the year 1969.

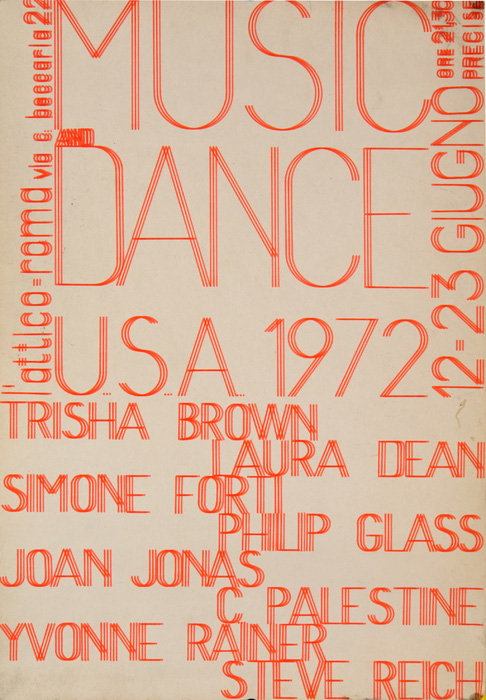

As anticipated by Forti’s exhibition and other initiatives hosted at the Piazza di Spagna space, ephemeral, time-based events mostly dedicated to dance, music, happenings, and performance marked L’Attico’s activity in its most dynamic years. On different occasions, Sargentini organized festivals that brought the crème de la crème of New York’s music-and-dance scene to Rome, and sponsored these totally not-for-profit activities by selling Surrealist and Informel artworks. Trisha Brown, Philip Glass, Steve Paxton, Charlemagne Palestine, Yvonne Rainer, Steve Reich, La Monte Young, Marian Zazeela, and others turned the former garage into a creative laboratory, an informal space of experimentation and exchange between different artists and their languages, which somehow reflected the kind of venues inhabited by the same artists and musicians in their New York lofts.

Sargentini found confirmation of the anticipatory nature of his new venue during two journeys that took place later in 1969: one led him to Bern to visit Harald Szeemann’s seminal “When Attitudes Become Form” exhibition, and the other took him to New York. In his reports penned for the magazine Cartabianca, evidence can be found of Sargentini’s particular interest in the nature of exhibition spaces and his clear awareness of the inadequacy of traditional museums and galleries when confronted with the new cultural methods of production and artistic expression. With his industrial, open, and vast space in Rome, Sargentini anticipated or immediately followed Paula Cooper in the use of lofts and warehouses by other New York galleries in the years to come, when they relocated their premises from Uptown to Soho.

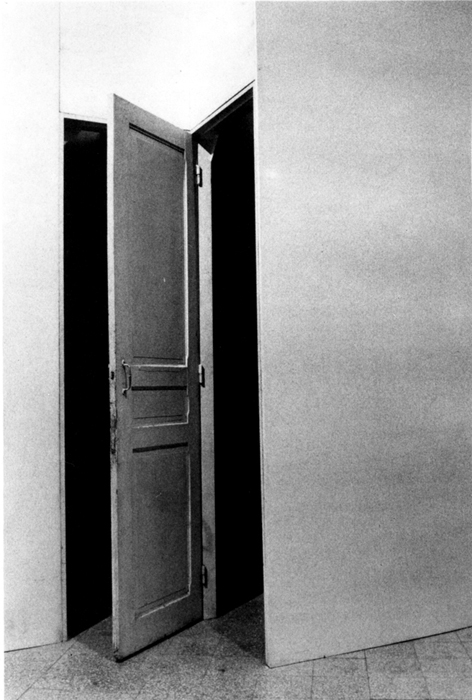

After a few years of intense activity in the garage, Sargentini understood that avant-garde extremes were about to look quite tired and outdated. Other artists were moving in a different direction, in search of new linguistic references that would privilege, for example, the format of tableau vivant to action. It was too early to call these stirrings postmodernism, but in the work of artists such as Gilbert & George, Luigi Ontani, and Giulio Paolini (not to mention Gino De Dominicis), a new dialogue with the past and art history was in place. Again following his intuition, Sargentini opened up a second space, once more in a historical venue in the center of Rome, with frescos and stucco moulding decorating the ceilings of different rooms. But in the Via del Paradiso space, he didn’t repudiate his long-standing interest in time-based practices and performances (Vito Acconci and Gilbert & George showed there in 1972; Nam June Paik in 1975), and for more conceptual-based expressions (Giulio Paolini; the door of Marcel Duchamp that Sargentini acquired and exhibited in 1973). While the space of the garage hosted more festivals (“Music and Dance U.S.A.,” 1972) and performances (Joseph Beuys in 1972 and Robert Whitman in 1974, just to name a couple), the venue on Via del Paradiso provided new and more articulated theatrical possibilities that became evident when Sargentini decided to change the gallery’s opening hours by closing it during the day and opening it during the night (in 1973), at one point even keeping the gallery open for 24 hours (1974). In both circumstances, Via del Paradiso hosted a series of events and actions orchestrated in different rooms.

This narrative would be incomplete if it failed to mention a third typology of space that Sargentini explored in many different circumstances: outdoor venues and public spaces. As early as 1968, he started to expand the perimeter of L’Attico initiatives, hosting events and actions in parks and other similar locales. Mattiacci, Marisa Merz, and Joan Jonas had performances in different outside locations, but probably the most memorable of these initiatives was the action conducted by Robert Smithson, in which a truckload of molten asphalt was dumped over the edge of some excavated ground on the periphery of Rome (Asphalt Run Down, October 1969).

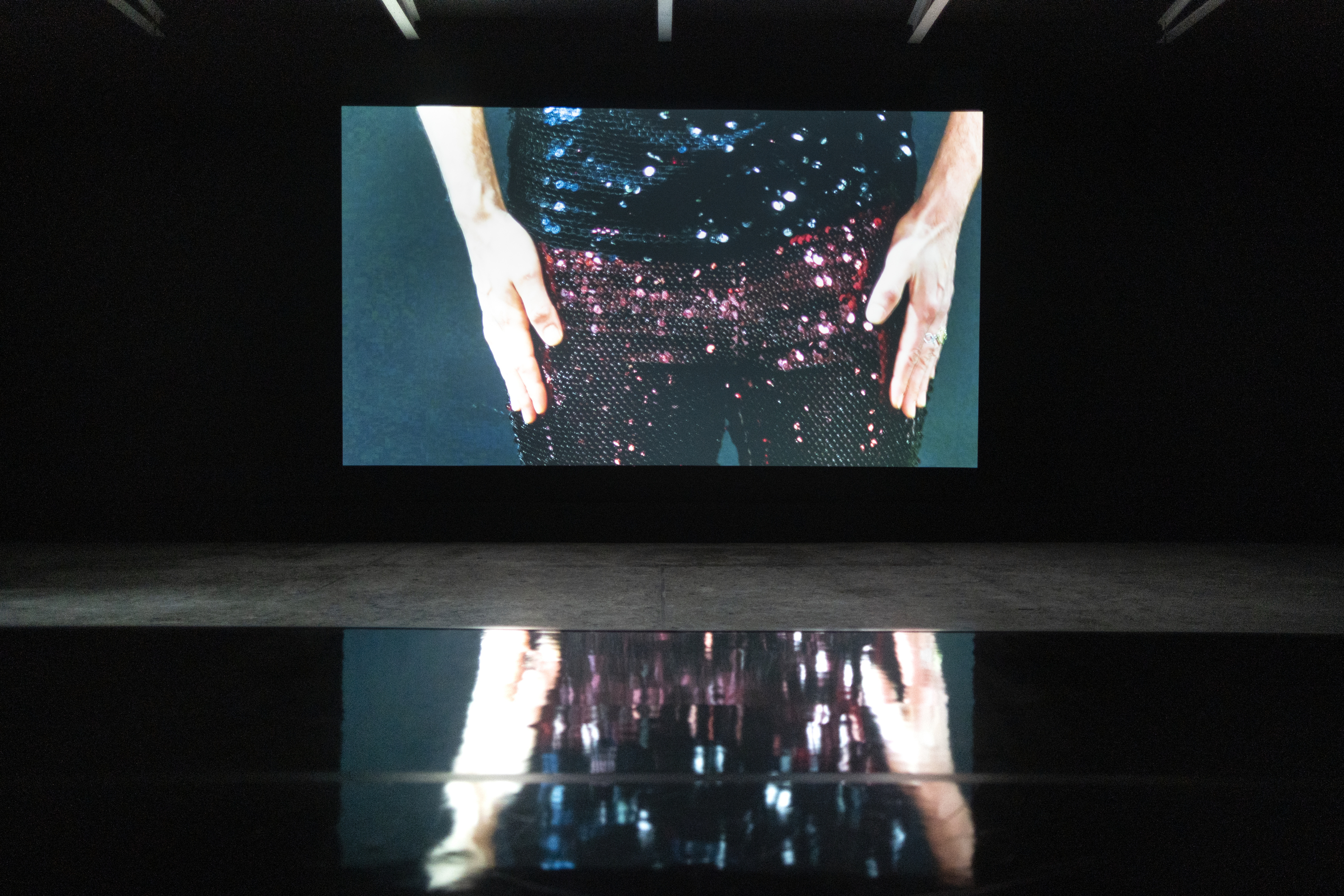

With the passing of time and the gradual exhaustion of the linguistic possibilities to be explored inside the exhibition space at Via Beccaria, Sargentini looked further for new directions in the gallery format. While in 1968 “Ginnastica mentale” transformed the function of the exhibition space within its own walls, in March 1976 Sargentini completed another “gesture” using the gallery as material. Under the title “L’Attico in viaggio” [L'Attico on the Move], he treated artists and friends of the gallery to a boat trip on the river Tiber, as if to suggest that a gallery can eventually exceed the borders of a physical space while maintaining its own identity. This new gesture anticipated the most spectacular of Sargentini’s performative operations as a gallerist/author/choreographer. In June 1976, he flooded the space of the former garage with 50,000 liters of water, putting an end to its intense activity. The volume of the gallery was thus instantly transformed into a motionless and transparent surface, and this final statement can be read as the perfect counterbalance to the accumulation of bodies, gestures, movements, actions, and events that occupied that same space for several intense seasons. The flooded space of L’Attico perfectly represented the end of an era and the silent finale in a long series of uncompromising gestures and activities.

As anticipated by “L’Attico in viaggio,” by the year 1977 Sargentini increasingly marked the gallery as a mobile and nomadic mechanism, agency, or think tank, when he organized two events that were related to India in different ways.4 After having sailed over the river Tiber, Sargentini brought some artists of the gallery (Francesco Clemente and Luigi Ontani, among others) much further, to the Indian city of Madras, while in Rome he organized the music and dance festival “India America.” Supported by the city council and hosted in a historical palazzo, the festival was a tremendous success. It brought in more than 10,000 visitors and had an important impact on the public cultural activities promoted by the city of Rome, events that in the ’80s would be labeled “Estati romane” [Roman Summers]. The ephemeral line that Sargentini championed within the perimeters of a private gallery and the confines of the avant-garde had by then gained broader visibility and entered the public realm.

While L’Attico and its artistic mission became an established part of the development of different forms of cultural production, Sargentini’s own activities also continued to evolve, this time towards his work as a theater writer and director. Even more so today, Sargentini’s artistic practices are closely entwined with his activity as a gallerist: one room of the exhibition space in Via del Paradiso has been recently transformed into a little theater that hosts performances and pieces by Sargentini and others. If L’Attico never inhabited the typical “white cube” exhibition space, the current “black cube” of a theater stage can be considered as possibly the last episode in Sargentini’s inexhaustible and constant search for new and different venues where art can be exhibited or, better, performed.

The inaugural exhibition of Arte Povera is considered to be “Arte Povera Im-Spazio,” curated by Germano Celant at Galleria La Bertesca, Genoa, September 27–October 20, 1967.

It is curious to note how, on exactly the same days in October ’68, Daniel Buren opened his first solo exhibition at Galleria Apollinaire in Milan. While Sargentini’s gesture was inclusive in nature and opened up the gallery to a new kind of action, Buren’s intervention operated thorough an act of exclusion. By sealing off the entrance to the gallery with a wallpaper marked by his typical motive of vertical stripes, Buren prevented visitors from entering the exhibition space, thus emphasizing the relevance of the “outside.”

At least since 1973, Indian culture and primarily music had come to occupy a strong position in the L’Attico program.