June 27–August 1, 2014

People who have lost arms or legs often report experiencing a “phantom limb”—the sense that the limb is still there, or that they can still move or feel it. It’s a good metaphor, too, for current post-internet art debates concerning the shifting relationship of real to virtual, digital to material. “Phantom Limbs,” Pilar Corrias’s smarter-than-most summer show, does a concise job of mapping the various poles of this cultural and theoretical inquiry. By assembling works that, broadly speaking, figure the human body as something caught in a world of networked relationships with images, technology, and other matter, the exhibition suggests that human subjectivity has in various ways been displaced or reconfigured—or maybe still implicated and entangled in the world, but no longer representing the Cartesian subject of an older, “anthropocentric” worldview.

If the footnoted gallery text is any indication, this exhibition wants to be taken seriously and plugs smoothly into current post-humanist critical trends. In addition to citing the written work of artist Hito Steyerl, the text makes grand pronouncements about the manner in which “notions of consciousness are evolving as a result of our digitally mediated experience.” It also asks leading questions like: “If we are able to feel […] sensations from something that is no longer present, at what point do they stop being an illusion and can be considered genuine?” Whether you’re a skeptic or a convert in this particular debate, there are a number of works in “Phantom Limbs” that are noteworthy in their articulation of some of these supposedly epoch-defining questions.

It’s perhaps inevitable that many of the exhibition’s standout works are videos; images of bodies on a screen have the advantage of dominating their own context of presentation (projection or monitor). Rachel Rose’s video Palisades in Palisades (2014), for example, is a remarkable experience that turns on the figure of a young woman hanging about in the wintery sunlit woods of New Jersey’s Palisades Interstate Park overlooking the Hudson River. Jumping back and forth between the park’s present and past identity as the site of the battle of Fort Lee during the American Revolutionary War, the camera zaps in and out of close-ups of the woman’s skin and eyelashes, as well as Revolution-era paintings—with details of uniformed men, navy ships, and cannons firing. It is as if the point of view of the camera were a bullet, piercing rather than merely observing its subject. There’s a vaguely feminist subtext in this linking of (male) militarism and phallic gaze, but when the girl utters, “um, I’m the voice of dead people,” in a distorted voice that doesn’t seem to be her own—or when the camera hurtles over her shoulder towards a rock in close-up view, or to the skin above her neckline—a bigger take-away emerges: this individual, or humans more broadly, merely represent one passage of a vaster, not exclusively human historical scale of reference—a view that invokes the work of Mexican philosopher Manuel De Landa and the “speculative realism” of the last decade.

In this exhibition, phantom limbs signal a failure of the distinction between subject and object, or maybe the loss of priority between them. And if you wanted to force the core question at stake in the kind of post-internet art presented here, it could be that human subjectivity is fast becoming the virtual, imaginary side of the equation. So in Cécile B. Evans’s 3D video, The Brightness (2013), a dialogue between two women—one supposedly a phantom limb specialist (uncannily also called Cecile B. Evans, who the artist consulted in researching the piece)—quickly unravels from a close-up of the woman’s sparkling white teeth to a delirious CGI sequence of Busby Berkeley-esque dancing molars. In the closing sequence, the two women speak, but again, voices and bodies are out of sync—there’s no verifiably secure, speaking subject, only mouths full of teeth.

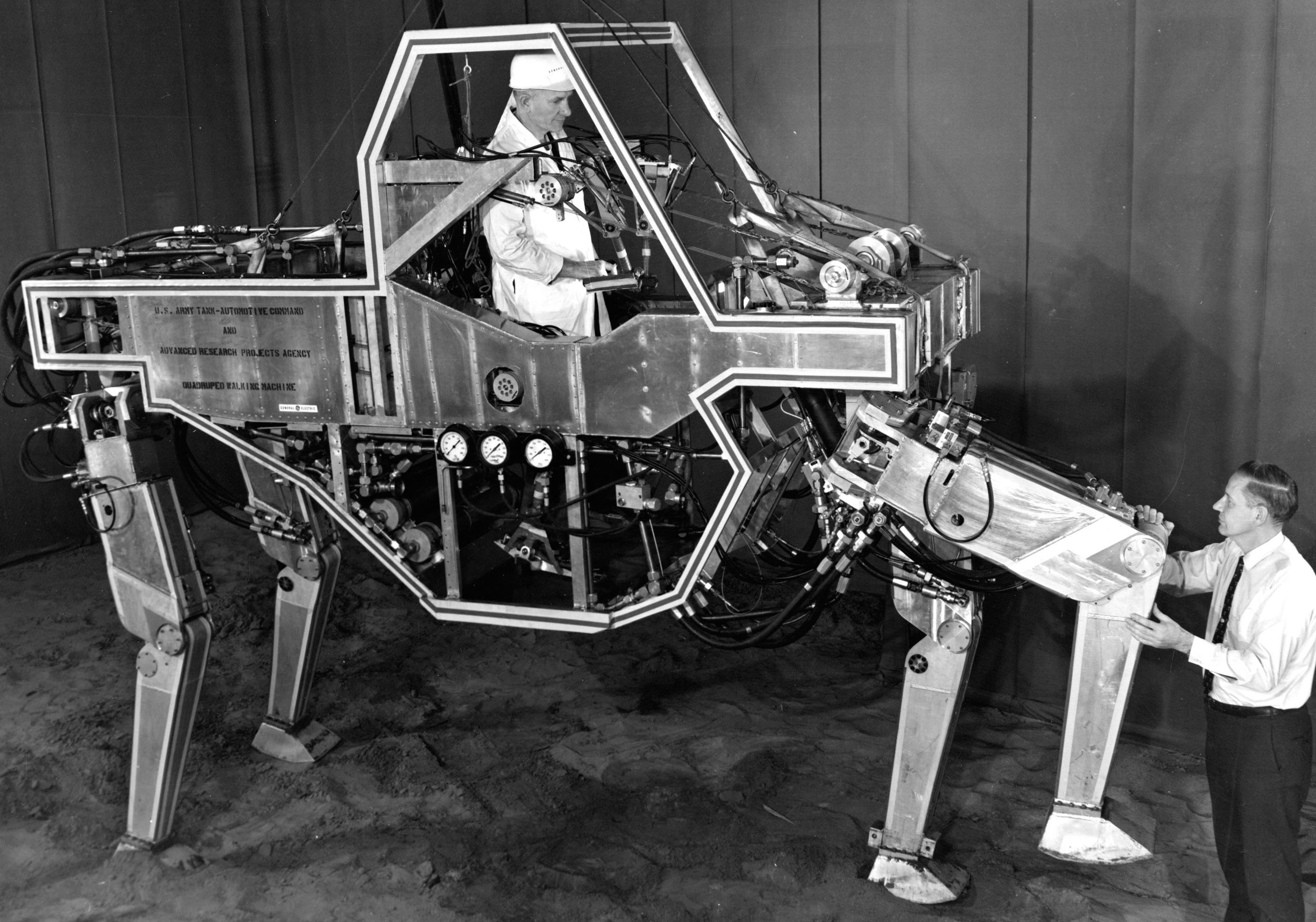

Speaking, conscious subjects don’t have much of a chance in “Phantom Limbs,” and autonomy isn’t much hoped for either, nor even particularly desired. Ken Okiishi’s video E.lliotT.: Children of the New Age (2004) follows the lives of two characters in a suburban house that looks like a derelict quotation of Steven Spielberg’s 1982 film E.T. Their autistic, bombed-out dialogue appears to channel science fiction, spiritualism, and esoterics all at the same time. Like his contemporary Ryan Trecartin, Okiishi obsesses over the collapse of interiority and the hallucinatory decentering of knowledge that is the inheritance of anyone who came of age with the internet. Such work suggests that subjectivity is not to be found in ourselves, but rather in a hazy middle ground, where subjects have become the prosthetics of a networked system of visual media. Similarly, Charlotte Prodger’s poised and arid looped video, Compression Fern Face (2014), coolly narrates cataloging-type descriptions of films made by an early 1970s performance artist simply referred to as “D.O.,” while two geometric V-shapes slowly turn opposite each other on screen, representing the authenticity of bodily experience converted to big data.

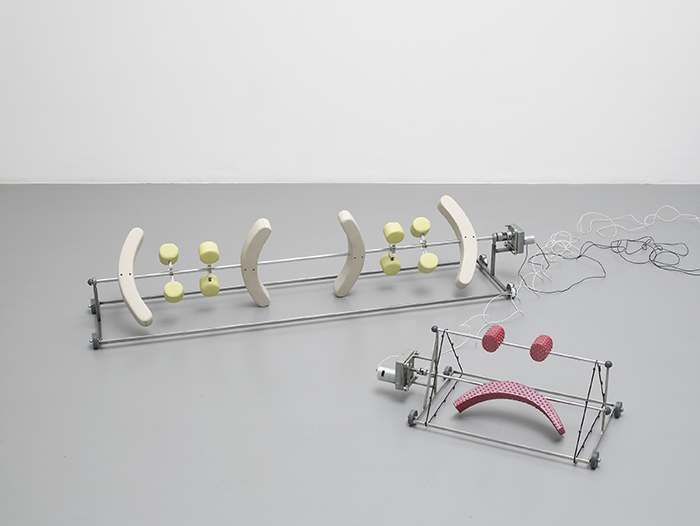

Images, networks, and language—freed from their origins as extensions of human subjectivity—become subjects themselves. Objects, too, register this shift in orientation: Antoine Catala’s materialized, motorized emoticons :) and (::( )::) (band aid) (both 2014) crawl across the gallery floor, bringing their message of happy and/or sad to no one in particular, while Alisa Baremboym’s sculptures are combinations of mass-produced goods (USB connectors, tubing, webbing) and crafted substances (fired porcelain and “gelled emollient”); they suggest internal, organic organization with lives of their own, away from us humans—although we still get to watch.

In a corner just inside the entrance, and thus easy to miss, is Philippe Parreno’s Happy Ending, Stockholm, Paris, 1996, 1997 (2014), a blown-glass recreation of a lamp once designed by Finnish-American architect Eero Saarinen (1910–1961). It seems shoehorned into a show whose concerns lie elsewhere (Parreno and Okiishi are the two gallery-represented artists), but its labyrinthine backstory—one of replicas lost and remade for spaces newly built or never realized—makes it a phantom of sorts, if only a weak echo of a work that would be much more pertinent here—Parreno and Pierre Huyghe’s 1999 project No Ghost, Just a Shell. But perhaps the figure of their “shell,” the manga character Ann Lee, would jar in the context of “Phantom Limbs” because this collaborative work, from a previous generation, still holds some pathos for the subjective emptiness of its protagonist, the absence of self. For the generation that figures in this show, however, there is no pathos, since there is no longer any self to lose.