October 19, 2016–January 15, 2017

“So long as we were in a room in a brothel, we belonged to our own fantasies. But once having exposed them, having named them, having proclaimed them, we’re now tied up with human beings, tied to you, and forced to go on with this adventure according to the laws of visibility.”1 When a confrontation with consequence reaches your door do you cloister yourself in safety, cower in fear, enter the fray, or resist that reality altogether? These are among the options presented to the characters of Jean Genet’s play The Balcony, an incendiary critique of power that has lost none of its urgency since its premiere in 1957. The name of the besieged brothel at the center of Genet’s play doubles as the title of the current edition of La Biennale de Montréal. More than just the title, The Balcony lends its ethics of eroticism to the proposition of biennale curator Philippe Pirotte and his team of advisers (Corey McCorkle, Aseman Sabet, and Kitty Scott): an emphasis upon the materiality artists engage with and in turn invite us to encounter, as well as a resistance to the kind of singular political proclamations that biennials often attempt to make. These intertwined impulses can be linked directly to the success and failure of “Le Grand Balcon”: the indelible power of artists’ projects and people when assembled thoughtfully in close proximity and the reticence to articulate and engage the urgencies outside of the art world in the autumn of 2016. Why here, why now?

This is the second iteration of the biennale in its current form, subsuming the former Québec Triennial, which presented exclusively Quebec artists, and finding a new home at the Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal (MAC). Unlike other peripatetic or site-specific biennials, La Biennale de Montréal, like its North American counterparts the Whitney Biennial and the Carnegie International, must work either within or against the histories and practicalities of the museum, including the display conventions of the white cube.

Here, the balcony is literally a beginning, with Nicole Eisenman’s 27 monotypes (2011) presented on the landing of the MAC’s second floor, overlooking the atrium. A dense hang of three tightly spaced rows of Eisenman’s monotype prints overlaid with paint—framed and uniform in size—invites visitors to look, and then look again as motifs and even individual images repeat. In two of them, a cartoonish character’s downcast eyes lead the gaze to their exposed genitalia. In another, a couple are interlocked in foreplay. In another two, eyes float freely and double as breasts. Faces mostly stare straight ahead. One of them peeks out from above a copy of Roland Barthes’s 1985 book of essays The Responsibility of Forms. Their beauty and complex formal articulation as a series simultaneously addresses both the isolation of individuals and the distress this inflicts upon bodies, as well as the erotics of exposure and the political act of public assembly.

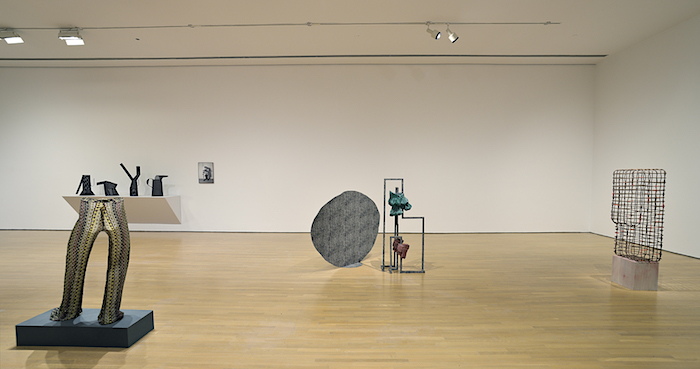

While the conventions of museum display might read as conservative, their limitations can produce their own kinds of pleasures. The most successful works in the biennale take on these conditions of exhibition and directly demarcate their occupation of the galleries. Exemplary in its command of materials and space is Celia Perrin Sidarous’s Notte coralli (2016), which encompasses a group of photographs (including collages and single images installed as murals) and a silent 16mm film, both presented around and upon a series of architectural structures. The film is dominated by static shots taken inside a studio setting with all the trappings of a still-life photography set. A pair of hands that enter from outside the frame to caress or control the accumulated objects disrupts these tableaux the artist has arranged upon monochrome backdrops. The photos are a mix of two kinds of images: still-lives made in the studio but also location shots that primarily capture a few different rugged landscapes, including some ruined temples. A large circle cut out from one of the architectural panels extends the potential pleasures of the viewers’ voyeuristic gaze from the surface of art objects to the flesh of one another.

The bodies on display in the work of Chris Curreri, like those of Nicole Eisenman, make explicit the questions of control between subject and object when encountering representations of bodies, and the liberatory potential of queer sexualities to produce ways of being together that exceed institutional regulations. In a gallery more intimately scaled than most at the museum, a series of petite framed black-and-white photographs hang in intervals around the perimeter of the room. Kiss Portfolio (2016) disorients through extreme close-ups of what are two sets of lips, but which alternatively suggest the sucking of a penis or the spreading of labia. In the center of the gallery stand three plinths. Upon them sits “Sixes and Sevens” (2016), a series of ceramics which appear undone, sagging as if deflated. While on their own they could constitute an anti-form gesture, alongside Kiss Portfolio they evoke the satisfaction of postcoital rest.

While Sidarous and Curreri both direct the choreography of the movement in and around their work, moving images demand stationary viewing and a unified gaze, acting as a thread throughout the galleries at the museum. Occasionally, the variable dimensions of projection appear as strategies to fill awkward spaces. David Lamelas’s 1974 film The Desert People is one of just a handful of historical guideposts in the exhibition, which also includes works by Hüseyin Bahri Alptekin, Thomas Bayrle, Cady Noland, and Lucas Cranach the Elder. Projected in the bright interstice between two larger, more spacious galleries, this underwhelming presentation has the unfortunate effect of making a vital work by Lamelas appear slight. The 16:9 ratio screen of Eric Baudelaire’s Prelude to AKA Jihadi (2016), however, is scaled thoughtfully in an expansive black-box. Using the “landscape theory” of Japanese filmmaker Masao Adachi—in which the spaces a subject encounters act as a kind of portrait in absentia—Baudelaire retraces the itinerary of Nabil, a Frenchman who traveled to Syria, allegedly to join ISIS. Without the presence of the subject and with no voiceover to guide viewers, the film captures on handheld camera the empathetic work of following Nabil’s footsteps. Likewise, the daylight that suffuses Moyra Davey’s Hemlock Forest (2016) is crystalline in another black-box presentation. In this companion to her film Les Goddesses (2011), Davey again conflates the act of reading and writing. With earbuds in place and her iPhone in hand, she haltingly recites a text she has composed and previously recorded as it is played back, criss-crossing the spaces of her apartment in New York, often with her own photographs anchoring each shot in the background. Her unflinching eye gives us a view onto her own body, her son Barney as he comes of age and transitions out of the family home, her attraction to Chantal Akerman’s News from Home (1977), and the long-term questions of making that arise from everyday life.

Of all the images excised from their original print sources—such as books and magazines—that are reassembled by Luis Jacob as collages under plastic laminate in his Album XII (2013-2014), one features an image with a polemic spray-painted across a wall that reads: “Architecture is the ultimate erotic act. Carry it to excess.” While this work shines off-site at Galerie de l’UQAM, the erotic pressure points accessed at the MAC are largely absent when the biennial moves out into locations across the city, a shift which speaks to local politics at play: while other Montreal institutions want to be seen as building support for the biennial, the off-site exhibitions are geographically scattered and inconsistent in quality, ultimately detracting from Pirotte’s curatorial concept. The humor and power of Kerry James Marshall’s Untitled (Rythm Mastr) (2016), a continuation of his Rythm Mastr comic strip, is undeniable, an incisive appraisal and occupation of city space through his characters. In a long horizontal group of light boxes divided into a series of panels, Marshall’s figures, drawn in high-contrast black-and-white and brilliantly backlit, directly address public access to art institutions and humorously deconstruct the assignment of racial identity. Requiring visitors to move through the streets from one museum to another in order to view the work allows viewers to evaluate their own place and privilege (or lack thereof) when navigating city streets as a resident or visitor, but its presentation at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, isolated from any other works, is a lost opportunity for dialogue. Likewise, the scattered presentations of work in artist-run centers and additional rented spaces in the former industrial spaces of the non-profit organization Regroupement Pied Carré in Mile-End, nearly an hour’s walk away from the MAC, leave captivating works by Em’kal Eyongakpa and Frances Stark adrift.

The limits of this biennale are the limits of the museum. In “Le Grand Balcon” the pleasure of these limits is cumulative, a model and material for making next time. As The Bishop advises in The Balcony: “Then we shall go back to our rooms and there continue the quest of an absolute dignity. We ought never to have left them.”2

Jean Genet, The Balcony (New York: Grove Press), 79.

Ibid.