October 20, 2017

The wide eyes and open mouth of a child are a reminder that, even at art fairs, there is still space for the occasional moment of wonder. The girl has good taste: she’s enthralled by Endless (2012), a sculpture by Claire Morgan at the FIAC booth of Galerie Karsten Greve. A three-dimensional grid of dead flies has been suspended in mid-air on vertical lines of nylon weighted with little pieces of lead. Around them, similarly hung dandelion heads form a slim, delicate frame. It is a gossamer-light and enchanting piece, whose dark eco-political agenda has been lent new urgency by recent research into insect decline.1

Animals seem, nonetheless, to be scampering throughout Paris this week. Also at FIAC, London’s Sadie Coles’ booth lures visitors in with Rudolf Stingel’s Untitled (2015), a black-and-white painting of a photograph of a squirrel. At the Musée de la Chasse et de la Nature, Sophie Calle interweaves the personal, the political, and the philosophical through a series of interventions, including covering the museum’s famous stuffed bear in a white shroud. Especially intriguing is a series of photographs (“Liberté Surveillée,” 2014) of deer, pheasants, and hares taken at night by automated cameras sited on the bridges and tunnels that allow animals to cross roads and railways. Like Stingel’s source material, Calle’s photographs restage the human visual encounter with animals: automated, reproduced, and taken without thought or permission.

More controversial has been Joep von Lieshout’s Domestikator (2015), a large, dark red sculpture that looks a bit like a building and a bit like a man having sex with a dog. The piece, recently on show at the Ruhrtriennale in Bochum, Germany, was scheduled to be displayed in the Jardin des Tuileries, near the Louvre, as part of Hors Les Murs, FIAC’s program of public art and events. But Jean-Luc Martinez, director of the Louvre, described the work as “brutal” and it was pulled from the program, prompting accusations of censorship. At the last minute, the Centre Pompidou stepped in and the work now stands in the courtyard outside. Van Lieshout himself said that Domestikator was a critique of humanity’s domination of the natural world. But then Van Lieshout says a lot of things.

The media controversy surrounding the work points to a comparatively recent development in the history of FIAC, and art fairs more broadly: the expansion from industry event into major public spectacle. As fairs proliferate across the world, each must work harder to distinguish itself. That is why Avenue Winston Churchill is currently lined with sculptures and why many of Paris’s galleries and museums save their best shows for FIAC week. It seems to be working: 72,000 people attended the fair in 2016. FIAC has the advantage of an unusually elegant venue: the Grand Palais (although what will happen from 2020, when the building undergoes renovation, is yet to be announced). “FIAC, like all important fairs, has become more than a fair,” says Vanessa Clairet of Galerie Perrotin, who describes it as the art-world equivalent of Paris Fashion Week. The French media’s excited coverage of Brigitte Macron’s blue minidress only reinforces the comparison.

The consensus among art professionals is that FIAC’s growth has helped Paris to become more global. Evidence includes the recent arrival of art fair Asia Now as well as smaller events like Salon du Livre d'Art des Afriques (African Art Book Fair) at Kader Attia’s La Colonie. “The Paris art scene used to be very local,” says Isabelle Alfonsi, co-founder of one of the city’s most consistently interesting galleries, Marcelle Alix. “But in the last ten years a lot of artists have been coming back. Paris is now a destination and FIAC has been an important part of that process.”

Animals abound at Karsten Greve’s Marais space, which is given over to a solo show by Morgan with larger-scale sculptures than could realistically be shown at FIAC as well as installation, paintings, and some exquisite drawings. Across the gallery are amorous peacocks, shrieking foxes, a crow, an owl, a finch, and more. What Goes Up (2017)—a combination of watercolor, pencil, and “residues of taxidermy process”—is an especially successful combination of delicacy and rigidity, order and chance.

At Asia Now, housed across multiple floors of an elegant Haussmann-era hôtel particulier, highlights include several deep blue acrylic ink works by Kim In Kyum at Korean Gallery SoSo; and small but complex paintings by Min Jung Yeon at Galerie Maria Lund that vibrate between figuration and abstraction. Meanwhile, at Paris Internationale, a supposedly alternative fair which is sponsored by Gucci, I’m seduced by works across sculpture, photography, and mapping by Stéphanie Saadé, presented by Beirut-based MARFA. A Map of Good Memories (2015) consists of 24-carat gold leaf pooled across the raw concrete floor like the silhouette of a beautiful nostalgia.

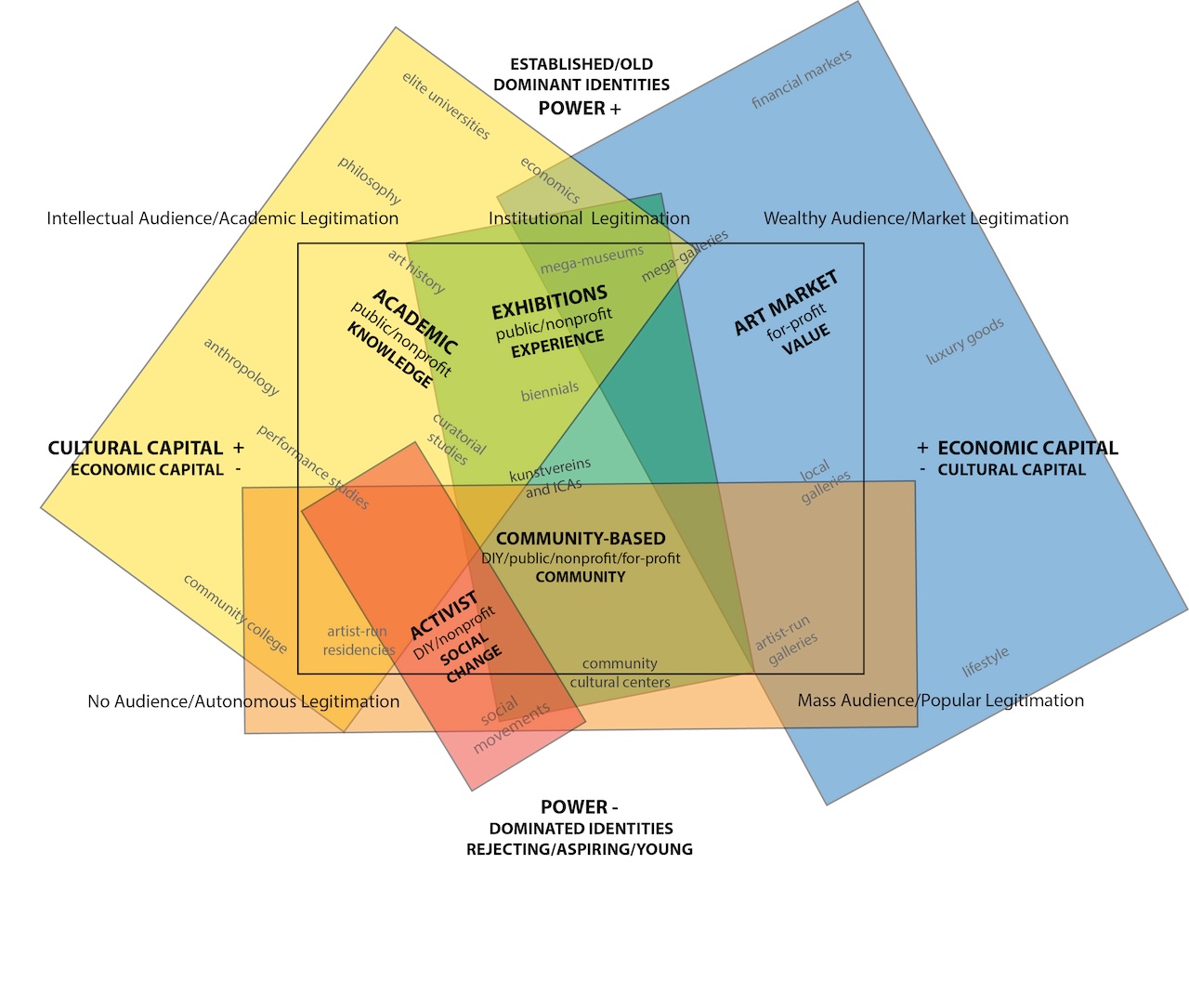

This proliferation of activities points to the increasingly complex interrelationship between different actors in the contemporary art ecosystem: commercial galleries, private collectors, private or corporate foundations, fairs, prizes, publishers, state-funded museums, even (last of all) the public. At FIAC, this is clear from the number of galleries using concurrent public exhibitions for commercial leverage. Both Milan’s Raffaella Cortese and Berlin’s Capital Petzel are showing works by Karla Black, who has a large-scale installation in the recently restored Salle Melpomène at Beaux-Arts de Paris. If you liked Maria Loboda’s photographs from the series “The Evolution of Kings” (2017), on show as part of Camille Henrot’s major exhibition at Palais de Tokyo, you can pick one up at FIAC thanks to Madrid gallery Maisterravalbuena.

Henrot’s “Days are Dogs” includes another image of interspecies intercourse, specifically a blue rabbit having sex with a man. Perhaps it is the medium (a gentle-hued fresco), the location (protected by an entry fee), or the roles taken by its subjects (the inverse of Lieshout’s) but Henrot’s work has inspired no comparable outcry. Or perhaps it simply got lost amid the overwhelmingly maximalist installation. The artist is represented at FIAC by three sculptures at Paris-based kamel mennour, at whose space on rue du Pont de Lodi she is also the subject of a solo exhibition, “Testa di Legno” [Wooden Head].

The crossover continues: Marcelle Alix’s booth includes Charlotte Moth, one of the finalists in the 2017 Prix Duchamp, currently on show at Centre Pompidou. Perrotin and New York’s Paula Cooper are both showing Sophie Calle, while one of the artist’s tiny flacons is also included in “Chambres à Part” at the new Musée du Parfum. The opportunistic displays are a reminder that FIAC is an art fair: for all the attendance figures or media coverage or performances or discussions or exclusive dinners, sales remain a significant arbiter of success. This year, most of the gallerists I spoke to seemed very content (but then who would admit otherwise?).

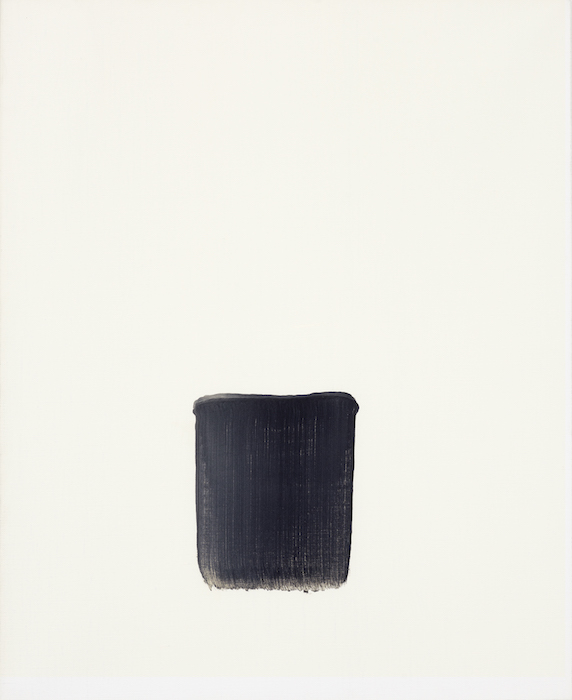

Within the hectic environment of the fair, contemplative paintings of quiet abstraction, signifying little beyond themselves, steal the show. At Seoul’s Gallery Hyundai, Lee Ufan’s Correspondance (1994) combines oil and mineral pigment in a single vertical brush stroke. Over at London’s Victoria Miro are three massive recent white paintings by Secundino Hernández (there’s also one at Vienna’s Galerie Krinzinger): each untitled and made from a combination of acrylic, rabbit skin, glue, chalk, calcium carbonate, and titanium white on linen. In each is one long vertical line of paired perforations that leads the eye up towards the arched glass ceiling of the Grand Palais and, before that, to the construction of the fair booth itself: a white frame and a line of staples holding white cloth to bare MDF. There’s a point to be made here about art, architecture, and the construction of value. But sometimes it’s nice just to stare wide-eyed.

Caspar A Hallmann et al, “ More than 75 percent decline over 27 years in total flying insect biomass in protected areas,” Plos One (October 2017), http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0185809.