November 23–26, 2017

Dublin is a dirty and disjointed city, a tangle of loosely connected neighborhoods best navigated on foot. On arrival my smartphone gave up the ghost, transforming the schedule of Dublin Gallery Weekend—a semi-coordinated program of exhibition openings, performances, and events—into a Situationist strategy. Deprived of online mapping services, I was forced to plot unusual paths between galleries across the city using a frayed, decade-old mental map. The resulting three-day drift along canal towpaths, through post-industrial edgelands, and down streets named for poets made it impossible to disentangle the experience of art from the emotional disorientation of travelling through the city hosting it.

Douglas Hyde Gallery is located at the bottom of Nassau Street, where students from Trinity College mingle with bookish tourists and frazzled shoppers. Abbas Akhavan’s “variations on a garden” seems initially to offer an oasis from the Black Friday bustle, the silence in the space interrupted only by the meditative drip of water into a shallow pool. That impression of sanctuary is reinforced, and then shattered, by an arrangement of bronze leaves, palm fronds, and flower stems (Study for a Monument, 2013-2016) arranged on the floor of the downstairs gallery. From the balcony, the sculptural installation resembles a set of botanical specimens for the visitor’s contemplation; on closer inspection these twisted strips of metal—enlarged bronze renderings of plants native to the banks of the rivers Tigris and Euphrates—read like wreckage from an explosion, and the white cotton sheets take on a sinister aspect.

By laying out on a shroud the flora that flourished in the Hanging Gardens of Babylon, an artist whose family was displaced from Tehran by the Iran-Iraq War suggests that no cultural site—whether garden or gallery—is ever insulated from the world. That conflict bleeds into every “safe” space is reinforced by Ghost (2013), a compilation of video clips in which US servicemen surprise their partners by returning early from active duty. Cast low onto a corner wall by a projector on a folding chair, the fraught reconciliations serve only to highlight the fear and resentment that pervade the home in the soldiers’ absence. The video is cleverly complemented by Mona Hatoum’s Roadworks, screened here as part of an initiative pairing Akhavan with an artist who has influenced his practice. This edited document of a 1985 performance—for which the Lebanese-born Palestinian artist walked barefoot through south London, dragging behind her a pair of Doc Martens laced to her ankles like balls-on-a-chain—explores what it means for an artist displaced by war to live amidst a community divided by simmering racial tensions. That she is followed by a jackbooted presence speaks not only to the daily intimidation of local women and minorities by bovver boys but also to the history of “stop and search” policing in London, a discretionary power whose abuse sparked the 1981 Brixton riots on the streets that Hatoum treads.1

Walking through the Liberties, a local curator tells me that the same policy has exacerbated tensions between local residents and police in this enduringly working-class district to the point that she was forced to move out of the area: it was suspected that she had reported a crime (the profiling here is along class rather than racial lines, with “reasonable suspicion” aroused by a combination of accent, youth, and dress). At Pallas Projects, at the heart of a neighborhood that a Panglossian speaker at the opening insists is now the city's “digital hub,” “Periodical Review #7” aims to generate a more cohesive sense of community among a disparate group of Irish artists. This “discursive action” presents work selected by four curators (Gavin Murphy, Mark Cullen, Rachael Gilbourne, and Kate Strain) on a clambering wooden structure which—on extruding plinths, shelves, and walls—accommodates a medley of sculptures, paintings, prints, and publications. The risk of this mode of exhibition design is that it reduces works by artists including Jesse Jones, Barbara Knezevic, and Sonia Shiel to components in a predetermined structure. Yet the architecture, precisely because it looked provisional and modular, succeeds in fostering a sense of community between works without flattening out their differences. An ambitious survey on such a small scale is necessarily unsatisfying—even when it succeeds, it leaves you wanting to know more about the featured artists—but this “Periodical Review” supplied an innovative framework on, over, and through which to understand new work.

That it does not necessarily benefit a work of art to be exhibited in isolation is confirmed by Shiel’s solo presentation “Rectangle Squared” at the National College of Art and Design on nearby Thomas Street. A circle of light at the center of a pitch-black gallery is circumscribed by six small cardboard figures representing characters in the audio play broadcast from the unidirectional speaker above their heads. The indebtedness to Beckett suggested by the staging—Not I (1972) is lit by a single beam which picks out the speaker’s mouth—is equally apparent in the script’s fractured monologues, but the comparison only reinforces that it’s a lot to ask of an audience to endure an hour-long, pre-recorded drama without any significant visual stimulus. The play itself—which addresses the difficulties of being a female artist—was occasionally compelling, but this nonetheless felt like an opportunity missed to showcase the multifarious practice of an artist much admired in Dublin.

After getting comprehensively lost looking for Kevin Kavanagh Gallery, a confusing combination of turns away from the Chester Beatty Library’s exhibition of Goya’s “Disasters of War” (1810–1820), it was apt that altered and obscured maps should be the subject of Ulrich Vogl’s “The Nature of Drifting.” Alpen – half restored (2017) is a 3D rendering of the Alps, the left-hand side of which has been “restored” to its edenic state by a conservator who has laboriously painted over any marks of human civilization. Like Akhavan’s petrified plants, the work plays on the impossibility of return to pastoral idyll, unless, perhaps, the earth is wiped clean by a human hand. That the best intervention the human race could make on behalf of ecological equilibrium is literally to wipe itself out is an admittedly thin silver lining to the looming mushroom cloud.

These gloomy thoughts were not dispelled by “The Ocean after Nature” at the Hugh Lane Gallery, which explores issues of migration and environmental collapse through works by twenty artists and collectives.2 An admirably intentioned show is awkwardly staged—with Peter Hutton’s At Sea (2007) projected weakly onto a lit wall half-obscured by Philip Napier's sculptures (Visual Amenity I and II, both 2010)—and demandingly long in its inclusion of so many time-based works. Yet it includes a strong screening program, which provides a rare note of optimism in CAMP’s From Gulf to Gulf to Gulf (2013), an hour-long video collage of footage shot by Indian, Pakistani, and Iranian sailors on their mobile phones during voyages across the Middle East and Africa. Their songs and snapshots from life on the ocean document the bonds between people and the differences between cultures, bridged but not diminished by trade. By challenging the assumption that the movement across borders is an homogenizing force, the work offers a reminder that the exchange of people, services and ideas can not only accommodate difference but stimulate new and hybrid forms.

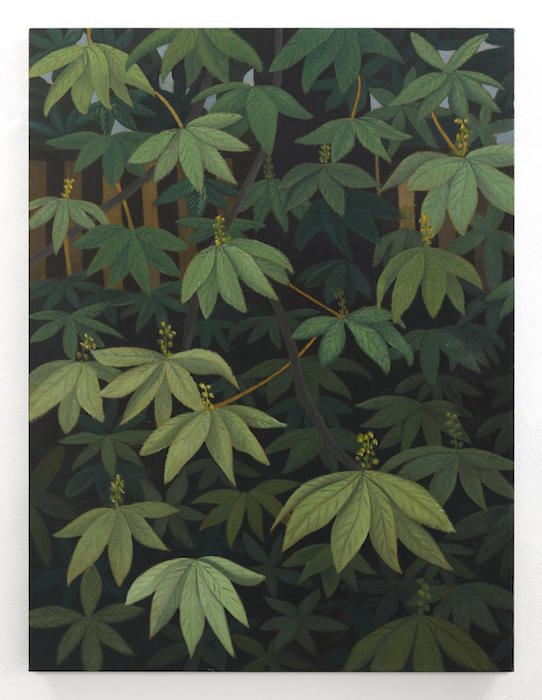

That much is apparent in the work of Stephen McKenna, whose paintings are exhibited at Kerlin Gallery. McKenna—who was born and studied in London, spent most of his life in Ireland, and lived at various times in Belgium, Germany, and Italy—was once asked whether he considered himself to be English, Irish, or European. “Yes,” he answered, suggesting that if he did belong to any community it was that branch of eccentric European painting to which Rousseau, Morandi, and Spencer also belong. Paintings such as Pyrrhus (2012)—with its postmodern collapse of high and low references—serve as a reminder that this port on Ireland’s eastern seaboard has always been a site of exchange.

I muse on how Dublin has been defined by its proximity to the sea—Viking slaving hub, prosperous trading port, fortified English foothold—as I traipse west along the torpid Liffey towards Mother’s Tankstation. I arrive at the gallery just in time to catch the climactic end of Rosalind Nashashibi’s Electrical Gaza (2015), one in a program of screenings titled “Being Infrastructural” and curated by the Dublin-based writer Maeve Connolly. Nashasibi’s eighteen-minute film (also on view in the Turner Prize exhibition at Ferens Gallery, Hull) combines live footage and animated images to conjure the febrile atmosphere of a city under siege. The contrast with the interior of the gallery—warmed by a freestanding iron stove, the audience plied with hot drinks—was in one obvious sense pronounced. Yet Nashashibi refuses to exoticize a city familiar from sensational news footage, focusing instead on the universal and everyday rituals—playing, shopping, gossiping, swimming—through which a unique sense of Palestinian community is fostered. The act of convening to watch and discuss films is just such an activity, albeit a privileged one; that these screenings are free to attend, open to all, and address the infrastructures on which societies depend makes it possible to reflect upon and expand that privilege. “Being Infrastructural” offers a reminder that communities are not merely the “same people living in the same place,”3 but are forged through cooperative activities, in communal spaces, in a dialogue of diverse voices, towards a shared system of values.

In 2017, black people in the United Kingdom were eight times more likely to be stopped and searched than their white counterparts: https://www.theguardian.com/law/2017/oct/26/stop-and-search-eight-times-more-likely-to-target-black-people.

No mention is made of the most obvious legacy of the ocean to this gallery. Collector Hugh Lane perished when The Lusitania was torpedoed by a German U-boat in 1915, an act that hastened the United States’ entry into the First World War. He took down with him a revised will with a codicil bequeathing his impressive collection to Dublin. London’s National Gallery, named as the recipient in an earlier will, refused to recognize the unwitnessed revision. The dispute continues to this day.

The definition of a nation given by Leopold Bloom—a cosmopolitan Irish Jew—to refute the one-eyed nationalist in Barney Kiernan’s pub. James Joyce, Ulysses (Oxford: Bodley Head, 1993), 12.403.