April 15–September 8, 2019

Not long before visiting Laurie Parsons’s exhibition at Mönchengladbach’s Museum Abteiberg, I had learned that the word “scrutiny” means “sorting garbage.”1 I was pretty pleased with the etymological alignment of the idea of critical examination with the condition of trashiness. To scrutinize is to look closely at that which otherwise goes unnoticed—but if trash can hold treasures, the reverse is also true; anything that has been sorted out can be turned back over to the generalized condition of the discarded.

Parsons, whose art career began with sorted garbage, is part of a lineage of artists whose work was once mistaken for worthless trash and thrown away: apparently, a well-meaning worker at a storage facility binned the rubble that the artist had collected for her work Field of Rubble (1988). She is also one of a number of artists remembered for having ghosted the art world. She started exhibiting in the mid 1980s, and less than a decade later (in what can be read as another act of scrutiny) she withdrew to do social work instead. Today, she mostly works as a service provider and advocate for people without homes and people with mental illnesses in and around New York City.

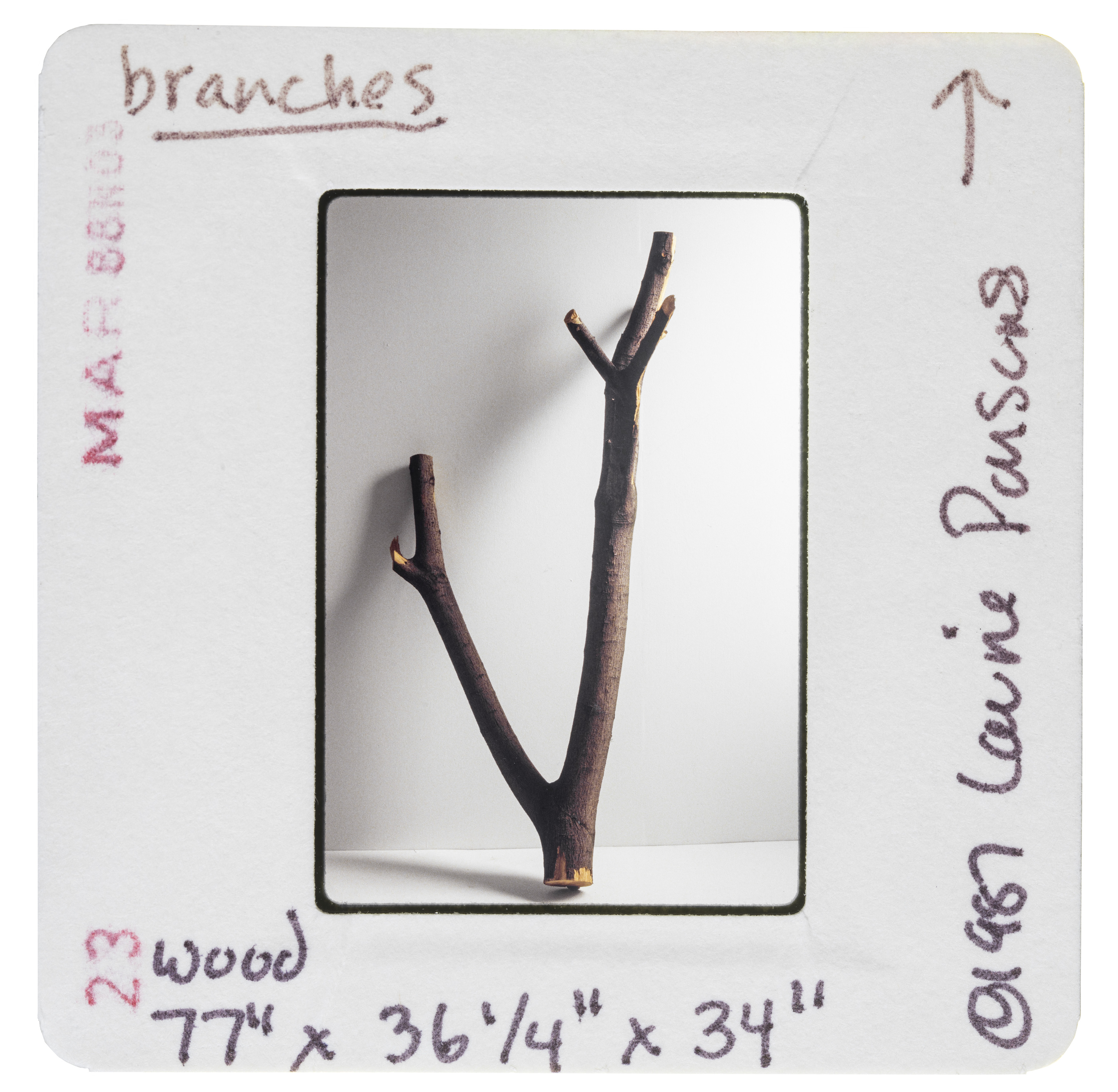

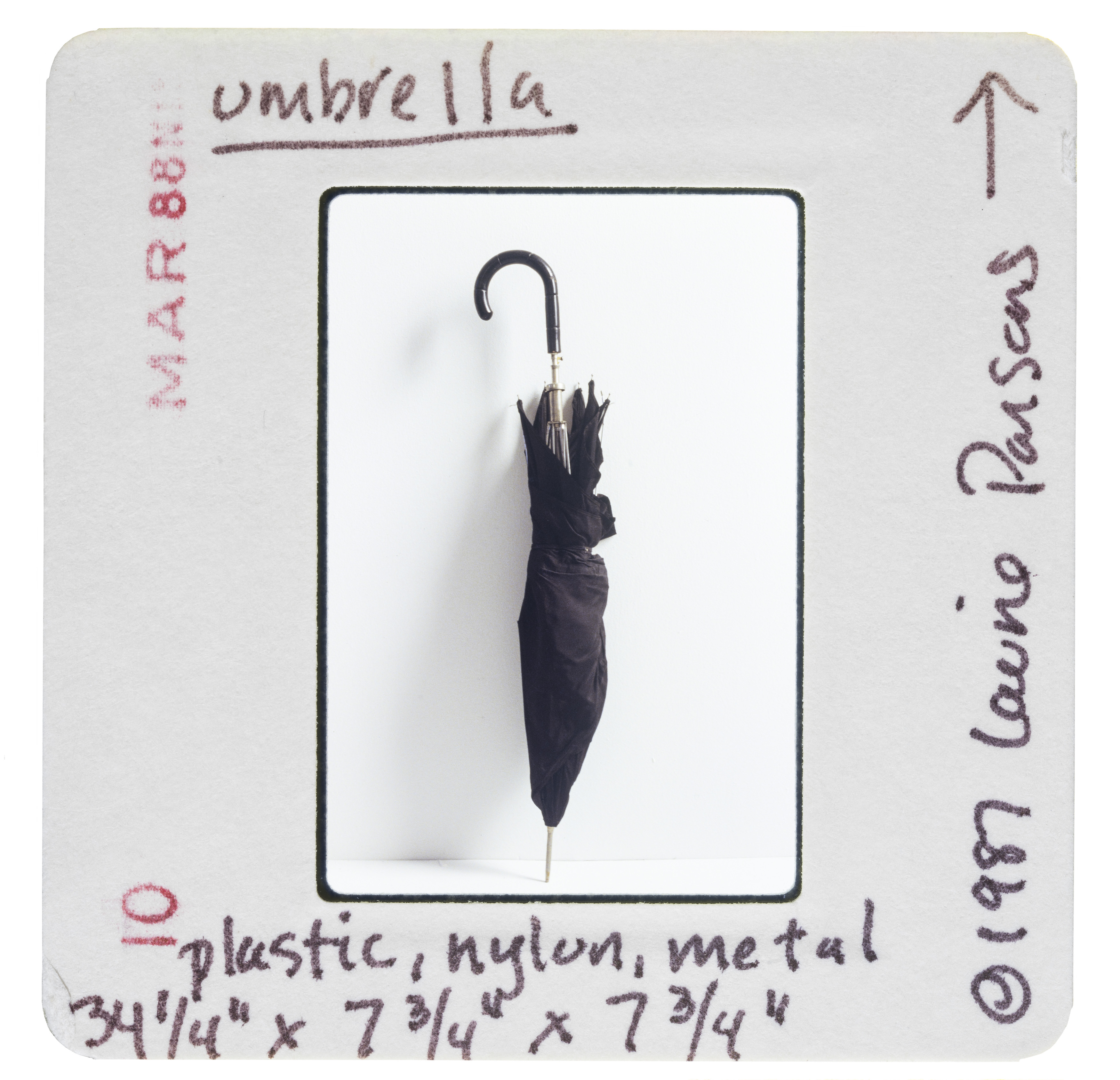

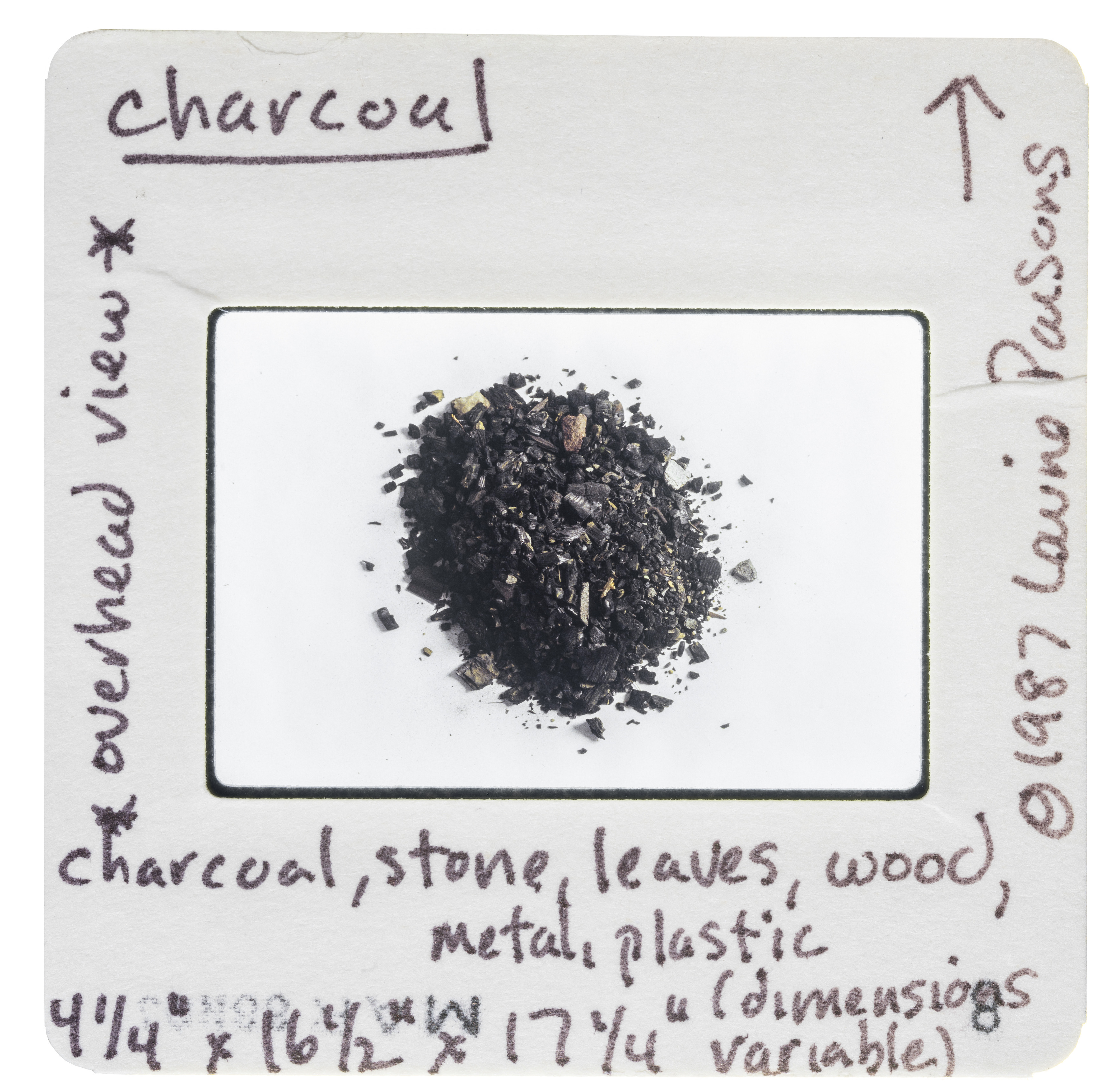

“A Body of Work 1987” presents a collection of objects that Parsons picked up from the streets around her New Jersey studio in 1987, including an old suitcase, a bicycle seat, a bunch of twigs tied together, a broken umbrella, an unearthed tree stump, some stones, a pile of charcoal, a bundle of rope, and a dirty, cracked bucket. They’re lined up around the edges of the room, more or less evenly spaced. With the exception of the wall-mounted bike seat, the objects are propped up against the wall or lying directly on the floor. There’s an atmosphere of casualness that approaches nonchalance, but it’s shot through with high-drama gravitas.

The objects were first exhibited in the artist’s first solo show, in 1988, at Lorence-Monk Gallery in New York, and again the following year at Cologne’s Galerie Rolf Ricke, after which they were purchased by a private collector. This exhibition marks their first public display since 1989. As with any historical re-enactment, things have changed. There are 28 pieces here instead of the original 29, because one scrap of woody debris was lost over the years. While the two original exhibitions were untitled, this one is titled with a phrase drawn from a certificate in which the artist referred to the objects as “twenty-nine pieces that together comprise a body of work.”2 There is also the sense that as the objects have become older and more fragile, they have accrued a new preciousness. When Parsons first showed them, they had recently been out on the street, worthless and unnoticed; looking at them today means looking at things that have been bought, sold, stored, transported, negotiated over, written about, documented, and otherwise tended to for over three decades.

According to Susanne Titz, Museum Abteiberg director, Parsons was consulted in planning this exhibition, and while she declined the invitation to come to Mönchengladbach, she did approve the team’s interpretation of the original installation instructions.3 This goes against a facet of the legend that has developed around the artist’s work in the wake of her exit, which tells us that she never talks about her previous contact with the sphere of art and she avoids all new contact with it. Perhaps one reason that this narrative of total final negation has propagated is that the work Parsons made during the years she was active as an exhibiting artist is so clearly characterized by gestures of subtraction and dematerialization.

For her second show at Lorence-Monk, in 1990, she gave the gallery a fresh coat of paint and adjusted the lighting, but no artworks were installed, so the space itself became the exhibited object. The announcement contained no mention of the artist, exhibition title, or dates, and Parsons later removed the exhibition from her CV. Invited back to Germany by Forum Kunst Rottweil the following year, she spent six months learning German before moving into the museum for the duration of the exhibition, hanging out with visitors and working at a local psychiatric hospital. The show was called “For the People of Rottweil.”

Parsons was attuned to the under-credited administrative labor that facilitates exhibitions. In 1990, for her contribution to a show at Andrea Rosen Gallery in New York, she became the office assistant for the duration of the exhibition. As part of the exhibition “1968” at Le Consortium in Dijon, in 1992, she had a weekly bouquet of flowers sent to the desk of Irène Bony, the institution’s administrator. (Parsons’s name was not mentioned on the announcements, but the flowers could be seen from the exhibition space through the office door.) One of her last works was the Security and Admissions Project at New York’s New Museum, in 1992. Confronting the institution’s unspoken policy that the security guards and admissions staff should not offer their insights or opinions about the art, Parsons instigated a new system whereby the museum’s wall texts and labels were removed, and visitors who wanted information could instead engage in conversation with the staff.

After that, no more art. Or at least, no more making new work within explicitly designated art contexts. Parsons didn’t develop an activist art practice or move into what came to be known as socially engaged art; she left, and part of what she left behind is the fact that she left.

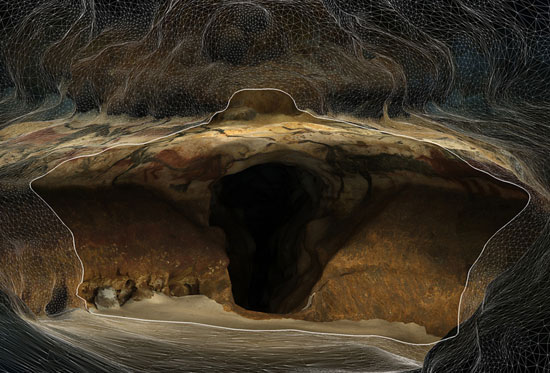

In accordance with the artist’s original display instructions, the lighting in the room for “A Body of Work 1987” has been switched off, so there is only natural illumination, through the overhead skylights. This makes for a stark contrast with the brightness of the museum’s surrounding rooms, which are filled with works from the collection by male artists who are also disproportionately illuminated by the canon. It takes a few minutes for the retina to adjust to the dimness (or at least it did on the overcast day when I visited), and there’s a sense that the objects are withdrawing from the brightest realms of historical visibility, while still being there at the shadowy edges, for readjusted eyes.

By connecting the interior space to the shifting conditions of the sky and the weather, the subtraction of artificial light also makes for a continual reminder of the world outside, which is always right there.

The Latin verb “scrutari” for “searching thoroughly” comes from “scruta,” meaning “scraps, rags, trash,” and initially referred to the practice of sorting through rubbish for items of value.

1989 certificate reproduced in the publication for “A Body of Work 1987.”

In conversation with the author, August 15, 2019.