September 12–December 1, 2019

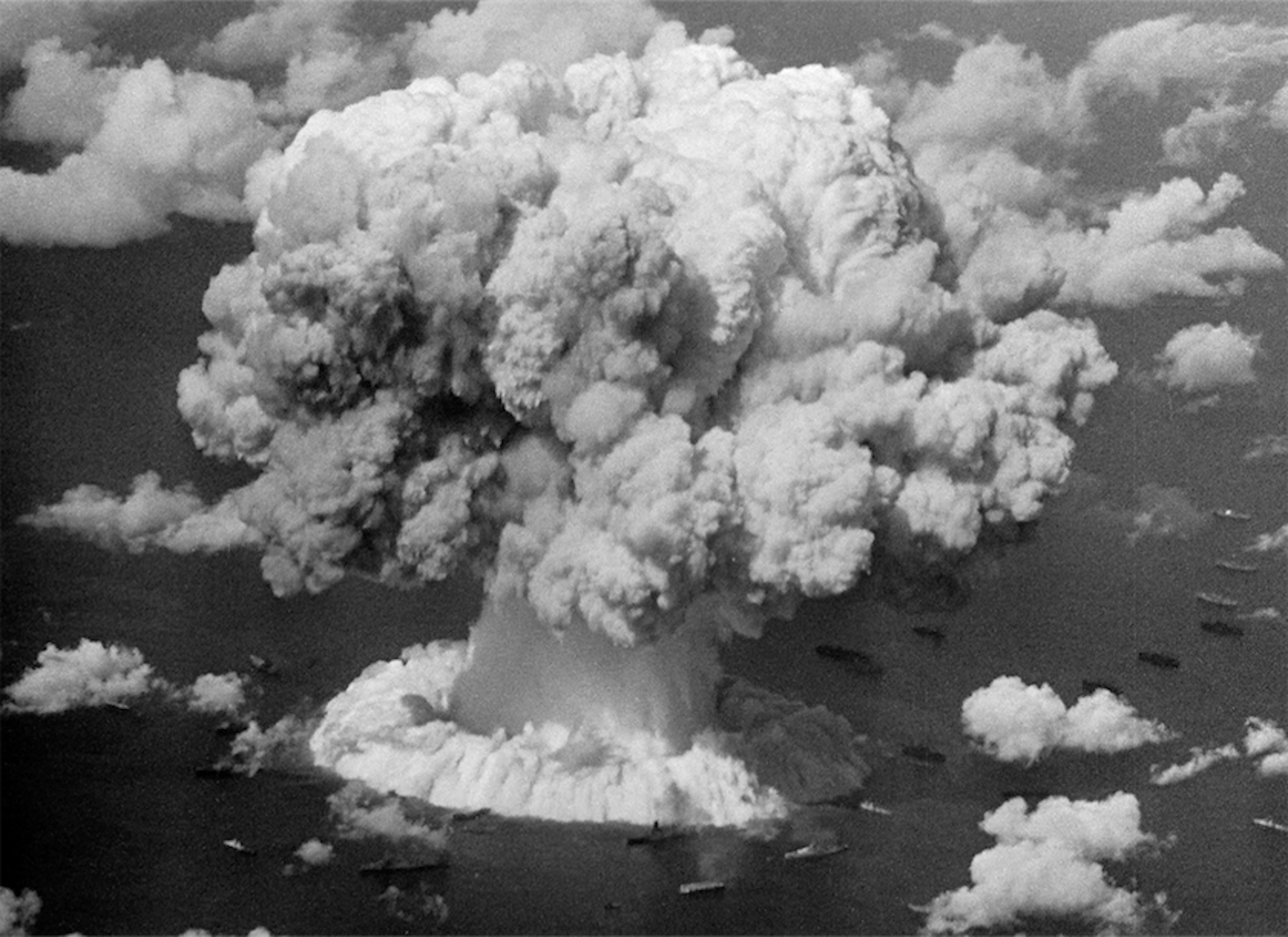

“Overcome the limits of immortality,” reads the catchphrase of the 5th Ural Industrial Biennial of Contemporary Art, curated by Xiaoyu Weng with the overall theme of “Immortality.” It’s a tricky one. I try to untangle it as I visit the vast labyrinth at the fourth floor of the Ural Optical and Mechanical Plant, the biennial’s main venue. A long corridor vanishes into the deep, its walls pierced with myriad doorways opening onto myriad rooms, opening onto further rooms, some of which open onto wide vistas of the Ekaterinburg cityscape. Shell-shocked by the explosive discrepancy between the scale and spatial illegibility of the exhibition, and the sparseness of its guiding framework, I stagger into a large, obscure space, where I’m adequately greeted by a nuclear blast, projected across the wall in mesmerizing, decelerated black and white.

It’s Bruce Conner’s CROSSROADS (1976). In an adjacent space, Peter Watkins’s dystopian docufiction The War Game (1965) is shown on a small video monitor, driving home the annihilatory point. It appears that technical development is not only a path to human salvation. I’m inclined to think that the exhibition’s catchphrase has dialectical finesse. Immortality, we can agree, is the same as non-death. And to overcome the limits of something is, in a sense, to negate it. Negate non-death, then. Die, for short. Might this be the meaning of the phrase?

Many other works support this interpretation. Death abounds. One space features a visually overwhelming installation by Carlos Amorales, Black Cloud (2007/2019): a dense swarm of black paper butterflies scattered across the walls and the ceiling. Their motif, their frailty, and the labor-intensive care with which they’ve been crafted all speak a romantic language of evanescence, of finitude. A few doors down, a two-screen video installation by Aki Sasamoto, Flex Text–Steel, Tensile Test–Steel/Brass (2017) restates the entropic argument but in different terms: its clinical, static close-ups show steel and brass bars being subjected to industrial stress tests. Tension escalates imperceptibly yet inexorably until the bars violently snap. Maria Safronova’s “Cabinet Series” (2019) of evocative, symbol-laden paintings of school interiors in ruin—imagine a postmodern Hubert Robert in Pripyat, perhaps—are among other works that support the moribund theme.

Facing Sara Modiano’s Cenotaph (1981/2019), however, I sense that this reading of the catchphrase might be insufficient. The work, a marble brick structure in the shape of a framed staircase leading down toward some unnamed underworld, is installed among a constellation of other works in a pillared hall at the deep end of the rabbit-hole corridor, after a tunnel of mirrors and a swamp of plastic mud. As the title indicates, Cenotaph evokes a monument or tombstone of sorts. The wall text refers to “pre-Columbian mortuary construction.” But a monument, of course, does not only commemorate the dead. It is also, as André Bazin once reminded us, engaged in a struggle against the passage of time, that is, against death.1 “Overcome the limits of immortality,” then, might also have a more straightforward meaning. What are the limits of immortality? For one, that it doesn’t exist. And so to overcome those limits could also mean to achieve it: to realize eternal life.

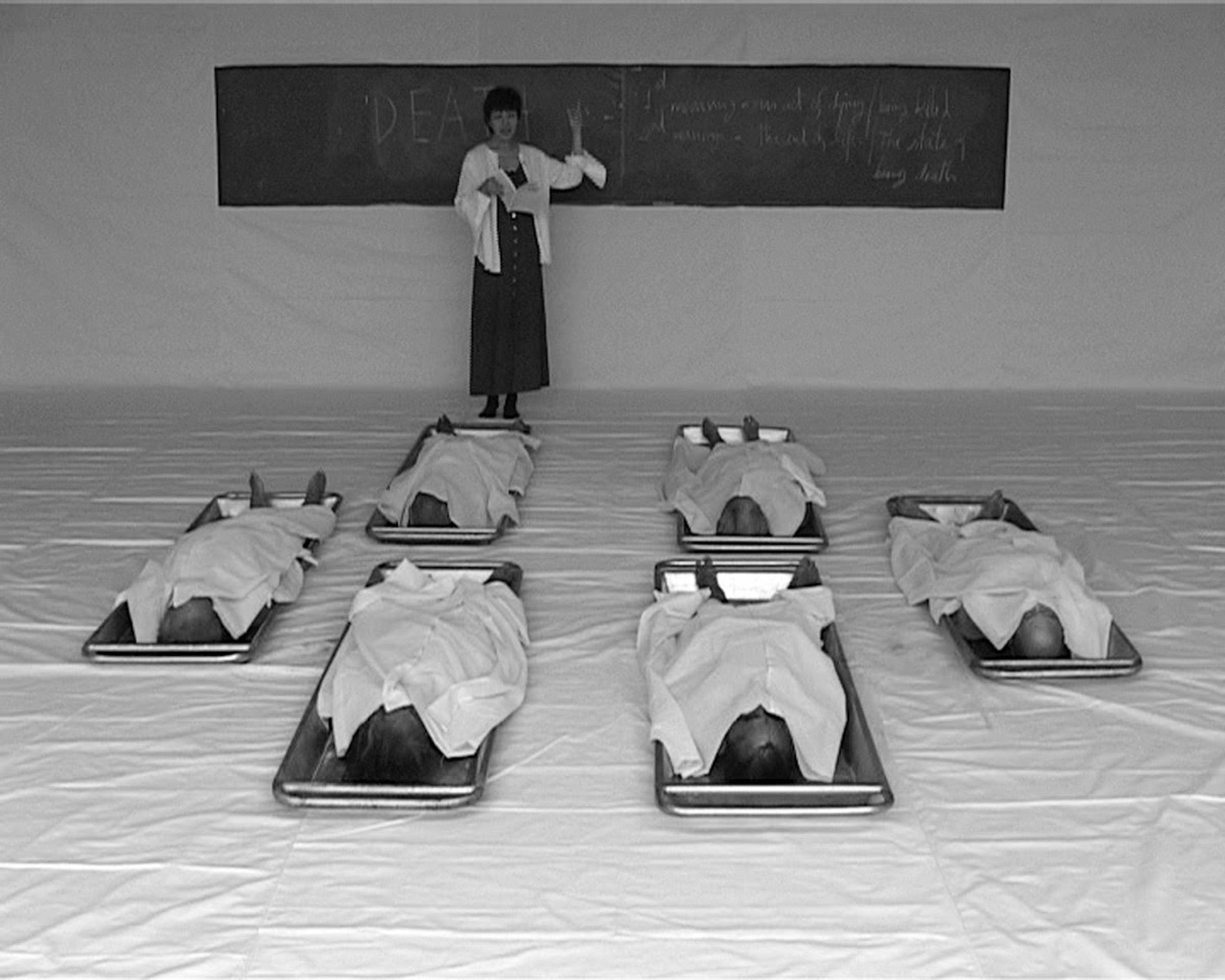

The introductory pairing of the exhibition appears to set out this idea. At the top of the narrow stairwell that leads up to the main exhibition floor is Nosferatu (2019), twin sculptures by Ivan Gorshkov. Slumped in a chair and sprawled out like a giant spider are two humanoid figures, their arms and legs stretched out into unwieldy, uncomfortable rods. They’re perhaps not diabolical, nor exactly posthuman, but they undeniably offer a reconfiguration of the human form. A monitor next to the sculptures shows Araya Rasdjarmrearnsook’s video The Class (2005), in which the artist delivers a lecture on death in a morgue. The audience, consisting of six corpses laid out on hospital beds, dutifully listen.

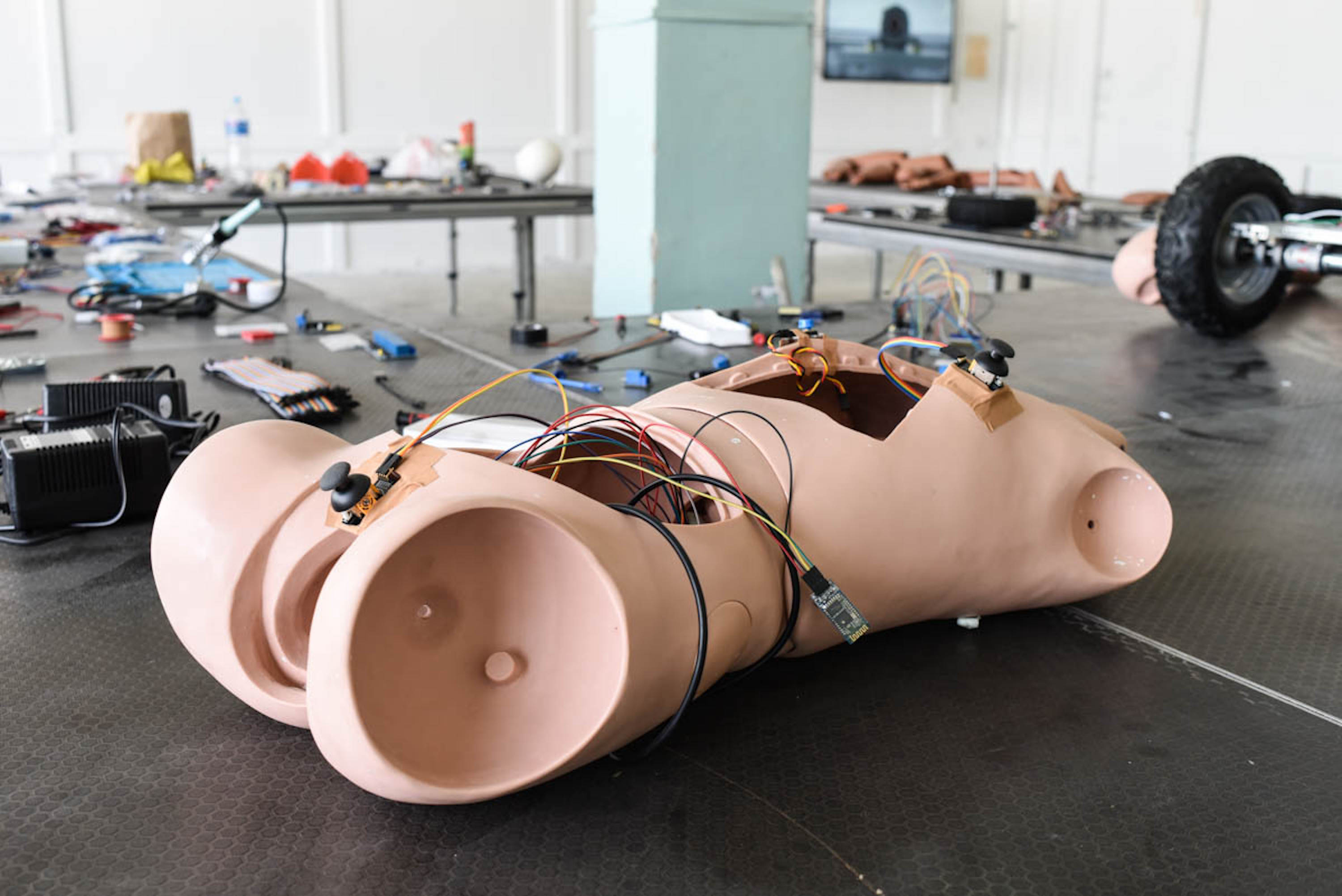

Resurrection, transcendence, immortality: the sequence is at work throughout the exhibition, not least in the section devoted to Russian Cosmism at the biennial’s second venue, the Coliseum Cinema in the center of town. And yet, back at the Optical and Mechanical Plant, as I ponder Geumhyung Jeong’s Small Upgrade (2019)—a vivisected, incomplete, homemade robot whose spare parts are scattered across a large operating or assembly table—this too feels like an insufficient reading of the catchphrase. Like other works in the exhibition that deal with new technologies—such as Chia-Wei Hsu’s Spirit Writing (2018), which restages a Chinese divination ritual using 3D motion-capture devices to demystifying effect, or Aram Bartholl’s installation Pan, Tilt & Zoom (2018), which puts auto-tracking surveillance cameras to unexpected use—Jeong’s disassembled body-mobile is all material finitude, no cyborg transcendence in sight. This is an exhibition that approaches technology as a historical, contingent reality rather than as a means to otherworldly bliss; as a problem rather than salvation.

Here the catchphrase becomes increasingly complex. The exhibition’s argument, as far as I understand it, concerns technological development and transhumanist discourse. The exhibition, one wall text states, “challenges transhumanist immortality’s universalist claims, which synchronize different temporalities into a singular future.” Instead it proposes a “reopening of passages to the past” which may also lead toward “a multitude of futures.” And so, on this reading, to “overcome the limits of immortality” would mean something like rejecting the reductive notion of immortality inherent in transhumanist discourse, in order instead to imagine other pasts and futures that set more complex notions of death and technology into play. That’s a rather specialized claim for a rather sprawling exhibition, but sure: few if any of the biennial’s artists appear to subscribe to some neo-techno-utopian fantasy according to which the human mind will ultimately be uploaded into the singularity and achieve everlasting life.

Which begs the question: Why even bother with the immortality theme in the first place? “Immortality”—the title of the biennial, recall—appears to be in open conflict with its own premise. Admittedly, this is an original curatorial maneuver. But it’s difficult to avoid the impression that contradictions of some more practical, organizational kind may also haunt the exhibition. That impression is confirmed by the fact that the biennial’s “strategic partner” is the corporation Rostec, a major state-owned conglomerate of Russia’s defense-industrial sector, which among many other things controls the arms manufacturer Kalashnikov Concern. What else than an exhibition on immortality could such a corporation comfortably support, one might ask? For future iterations, the biennial’s organizers should reconsider their financial partners.

On the main floor of the Optical and Mechanical Plant, these unresolved conceptual and organizational contradictions translate into a somewhat chaotic and often illegible exhibition. Two floors down, things are clearer. Works from the biennial’s residency program are displayed in a way that offers ample space for each contribution. Still reeling from sensory overload and labyrinthine disorientation, I find myself sitting relieved in front of what is one of the best works in the exhibition, Naïmé Perrette’s Both Ears on the Ground (2019). It’s an essay film shot in Berezniki, a city in the Urals known for the large sinkholes that suddenly opened up in its ground, swallowing industrial buildings and infrastructure.

Perrette’s film, however, doesn’t indulge the viewer with more sensationalist shots of the fateful chasms. Berezniki’s citizens don’t care about the sinkholes, and are sick and tired of journalists and film crews asking about them. Instead, Both Ears on the Ground is framed as an investigation into how these disasters have been reported and depicted, and how the citizens are seeking to image their own future, beyond enticing narratives of impending doom. This careful approach seems to have gained Perrette a certain trust among the city’s inhabitants. She gets access, for example, to film in one of the potash mines beneath the city. Proud miners show a vast, white cavern deep in the mountain, its walls covered with ornament-like traces from the excavation process. An enormous mining drill determinedly burrows its way through salt deposits. The driver of the machine appears slightly bewildered by the attention and explains that he likes to advance, to go forward.

André Bazin, “The Ontology of the Photographic Image”, trans by. Hugh Gray, Film Quarterly, vol. 13, no.4 (Summer, 1960).