In the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, the Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art elected to establish an annual festival addressed to a changing world and proposing “survival strategies.” Now in its thirteenth year, Survival Kit takes place under the shadow of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine and its implications for a country in which around one quarter of the population are Russian speakers.

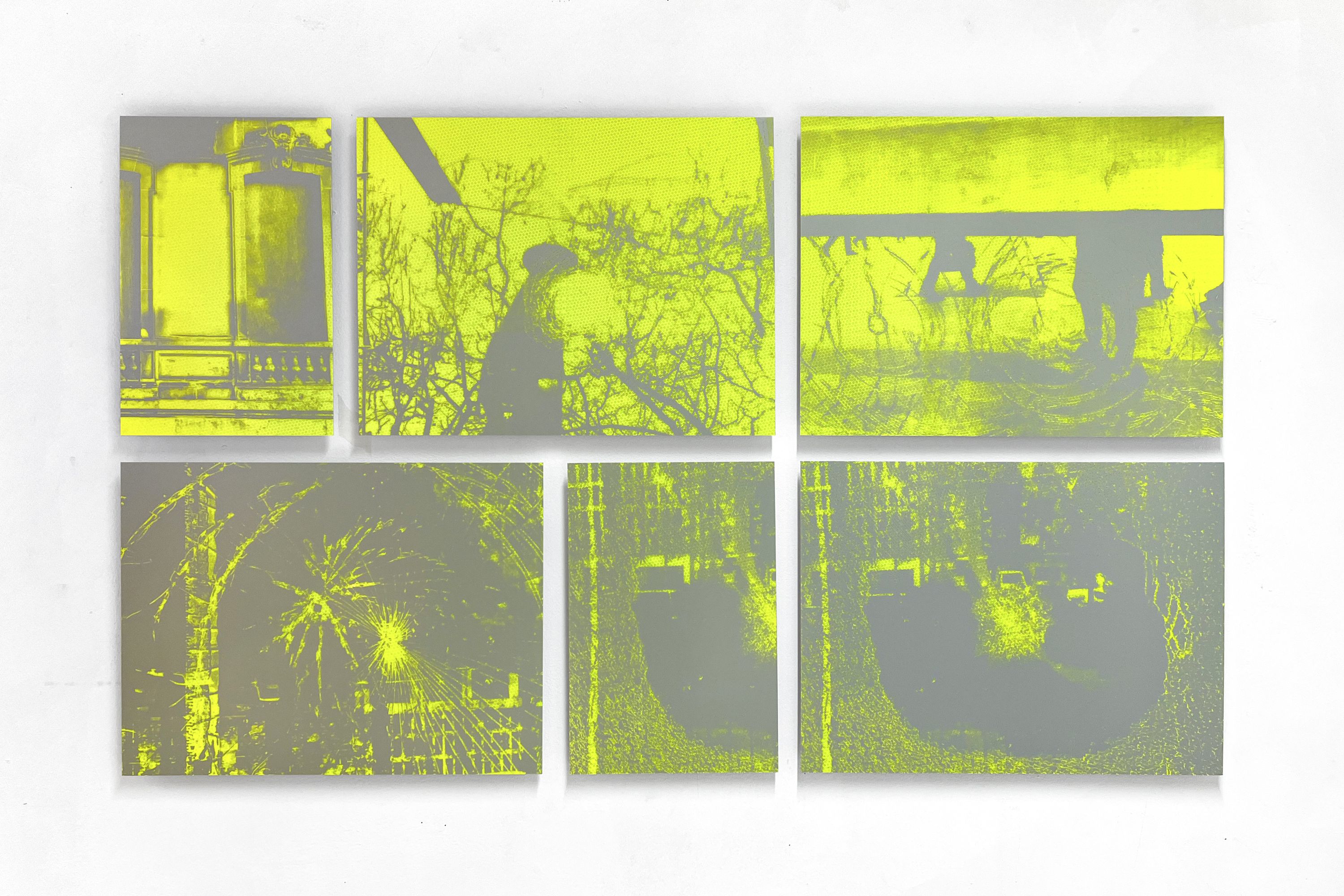

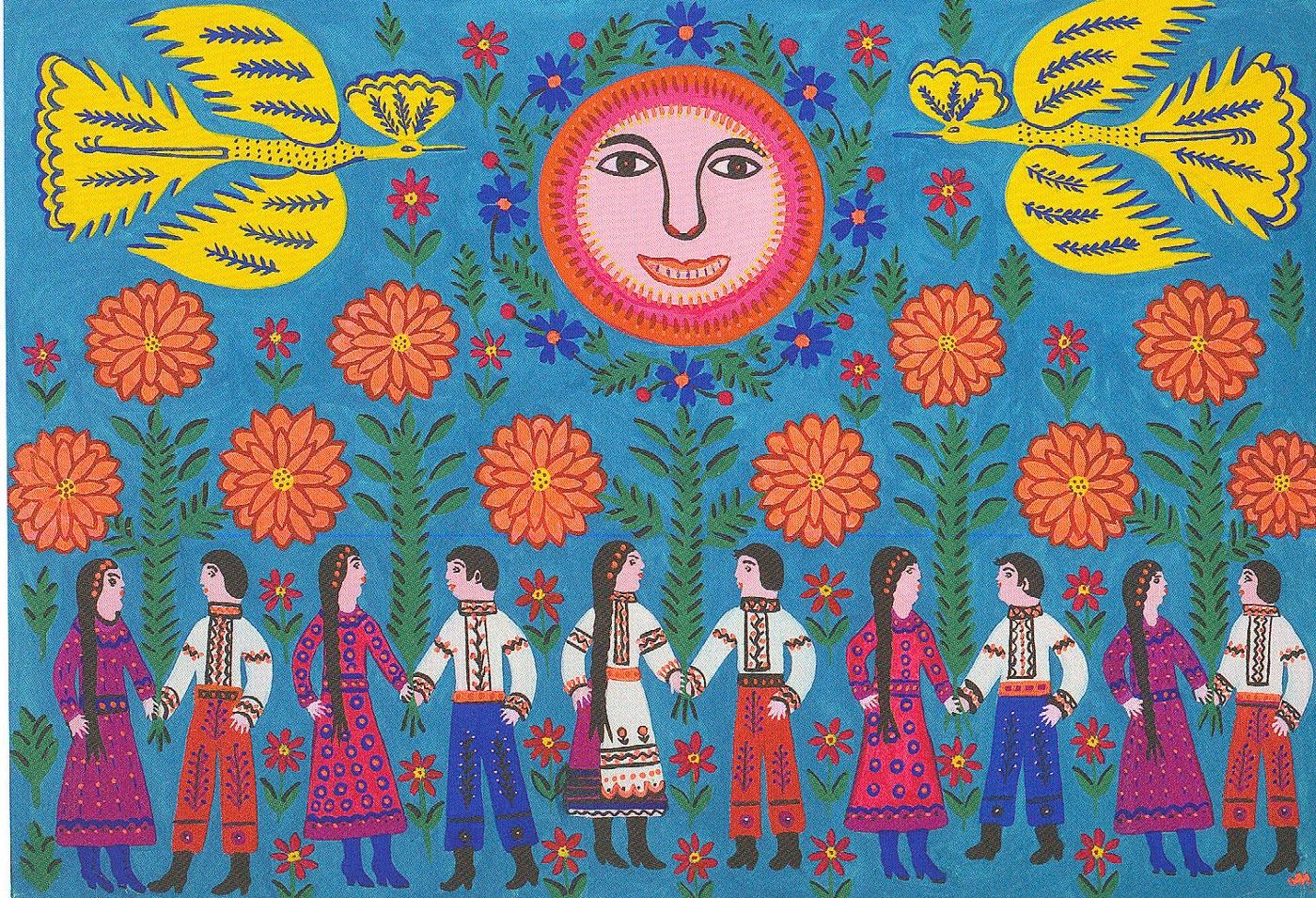

An exhibition curated by iLiana Fokianaki and taking inspiration from the “Singing Revolution” that preceded the Baltic States’ independence from the USSR has clear resonances with the present situation in Eastern Europe, but also reverberates more widely. Poetry, music, and song are figured by artists from Andrius Arutiunian to Wu Tsang as powerful expressions of resistance to imperialism, not only as the vehicles by which marginalized traditions are transported into the future but also as defiant expressions of feelings that cannot be suppressed. After seeing the exhibition in Riga last month, we talked to Fokianaki about a world in flux and the role of art within it.

art-agenda: A year ago you proposed a show which would consider the impact of rising authoritarianism on issues of national identity and free speech through the lens of Latvia’s historical relationship to Russia and the USSR. How did the outbreak of war change your framing of the exhibition?

iLiana Fokianaki: I have been looking into the influence on the development of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania of the legacies of Stalinism since a trip to Lithuania in early 2020. These issues were much exposed in the western media during the early nineties, and then left aside. Of course, they resurfaced when Putin expanded his invasion of Ukraine in February. But the core thematic of the exhibition did not change. The umbrella questions under which it operates are: What is the relationship of art to democracy, and how does that unfold on a sonic landscape? What is the role of sound, as it relates to artistic practice, in defining, marking, contouring, and characterizing historical moments of emancipation? There is an emphasis on music and oral culture as forms of peaceful protest, declarative gesture, and collective performativity.

AA: Your contextualizing essay makes clear that these are ideas that can be applied beyond Eastern Europe.

iF: I wanted to underline that authoritarianism, state violence, and neo-colonial behaviors are not exceptional and exclusive to Putin. There is an array of examples in the twenty-first century of aggressions, repressions, suppressions, and censorships, many times in supposed democracies. It was very important for me that this is evident in the variety of geopolitics represented in the exhibition. It is an intergenerational approach that breaks with linear time: we see works by Sanja Iveković that discuss silencing during Tito’s Yugoslavia [specifically documentation of her opening performance at the Zagreb Gallery of Contemporary Art in 1976], but also works of hers that discuss women’s silencing and repression [Übung macht den Meister, 1982/2009]. We also see work by younger artists such as Kapwani Kiwanga and Tabita Rezaire made during the pandemic and protests in support of the Movement for Black Lives.

AA: You write about how it is a strategy of “narcissistic authoritarian statism” to drown out other voices by shouting over them. There are a number of spoken-word sound works and video installations in the show (by Kapwani Kiwanga, Laure Prouvost, Erica Scourti, Candice Breitz). How does the inclusion of these works, and their arrangement within the space—it’s notable that the sounds never bleed or compete—express an alternative politics of speaking and listening?

iF: I identified “narcissistic authoritarian statism” as a new style of governance a few years back, with the election of Trump, Bolsonaro, and others. It is characterized by the drowning out of reason by shouting about “freedom of speech,” followed by corruption, collusion with private interests, climate crisis denial, racism, sexism, and so on.

I would have liked this phenomenon to last only a few years, but Viktor Orbán was recently re-elected; Austria was almost taken over by neo-Nazis; my own country, Greece, has elected a government with authoritarian tendencies currently dragging us through the mud with illegal pushbacks of refugees and a Greek Watergate; Italy has just voted in a neo-Fascist government; Trump has never gone away; Xi Jinping is consolidating his power in China...

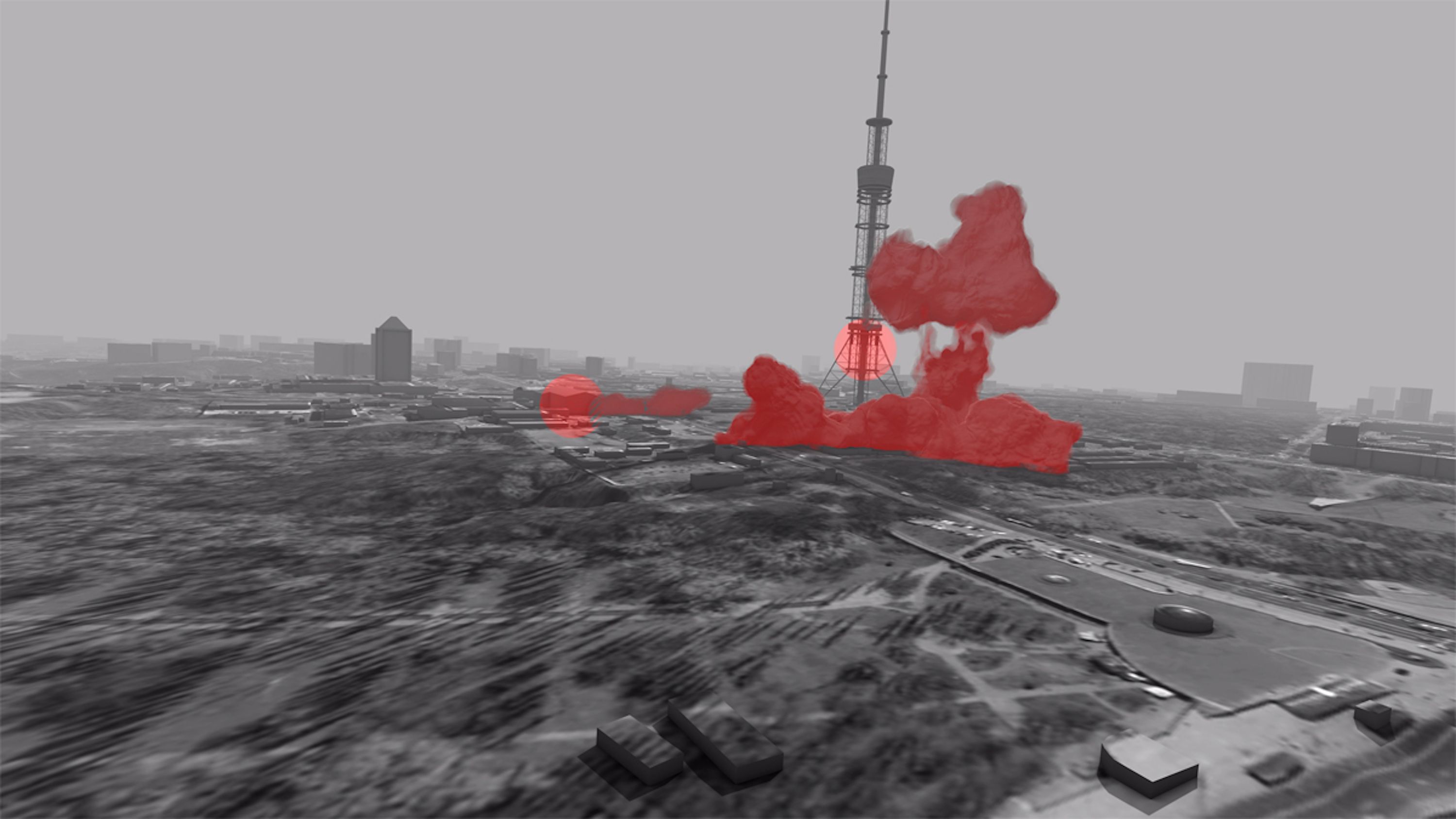

I am not sure whether the works you mention express an alternative politics of speaking and listening so much as unmask the effects of contemporary power on our bodies and lives: in Kiwanga’s work we hear the frustrations of the diaspora subject who loses their mother tongue; Prouvost and Scourti address the exhaustion of the overworked body and mind within today’s turbo-capitalism. Breitz’s new video installation turns the mirror onto whiteness and white supremacy in a magnificent way, weaving together examples of alt-right media together with the less obvious racism of liberal “good whites.” But yes, the aim was for one sound to lead to the next without them competing against one another.

AA: As well as speech there is a lot of song, frequently figured as liberatory or anti-authoritarian: in the works by Susan Philipsz, Rojava Film Commune, Wu Tsang, and others. Could you elaborate on the function of song within the show’s curatorial framework? This is something we’ve seen in the news very recently, with the Russian authorities’ decision to list the rapper Oxxxymiron as “foreign agent” and the detention of the musician Shervin Hajipour in Iran.

iF: There is a long tradition of singing as resistance. Chilean women sang during protests in support of the men who’d been “disappeared” by the Pinochet regime, I was lulled to sleep by my partisan grandfather singing songs from the Greek Liberation Front. Aside from the role of the artist as recorder of authoritarianism’s effects, or archivist of oral history, singing as an act in itself, and its liberating properties, is extremely important in how we understand the role and relationship of sound to democracy.

It is also universal, in the sense that this form of resistance is practiced throughout the world. Latvia was part of what was known as the “Singing Revolution” in 1991, and a key part of the process of liberation were interventions in Folk Song festivals under Soviet rule in the late 1980s. Collective singing was an act of rebellion. So the works tie-in these historical moments. In the case of Rojava Film Commune, the film highlights the common musical legacies between Assyrian, Arab, Yezidi, and Kurdish people of the region. Song embodies examples of solidarity and living together.

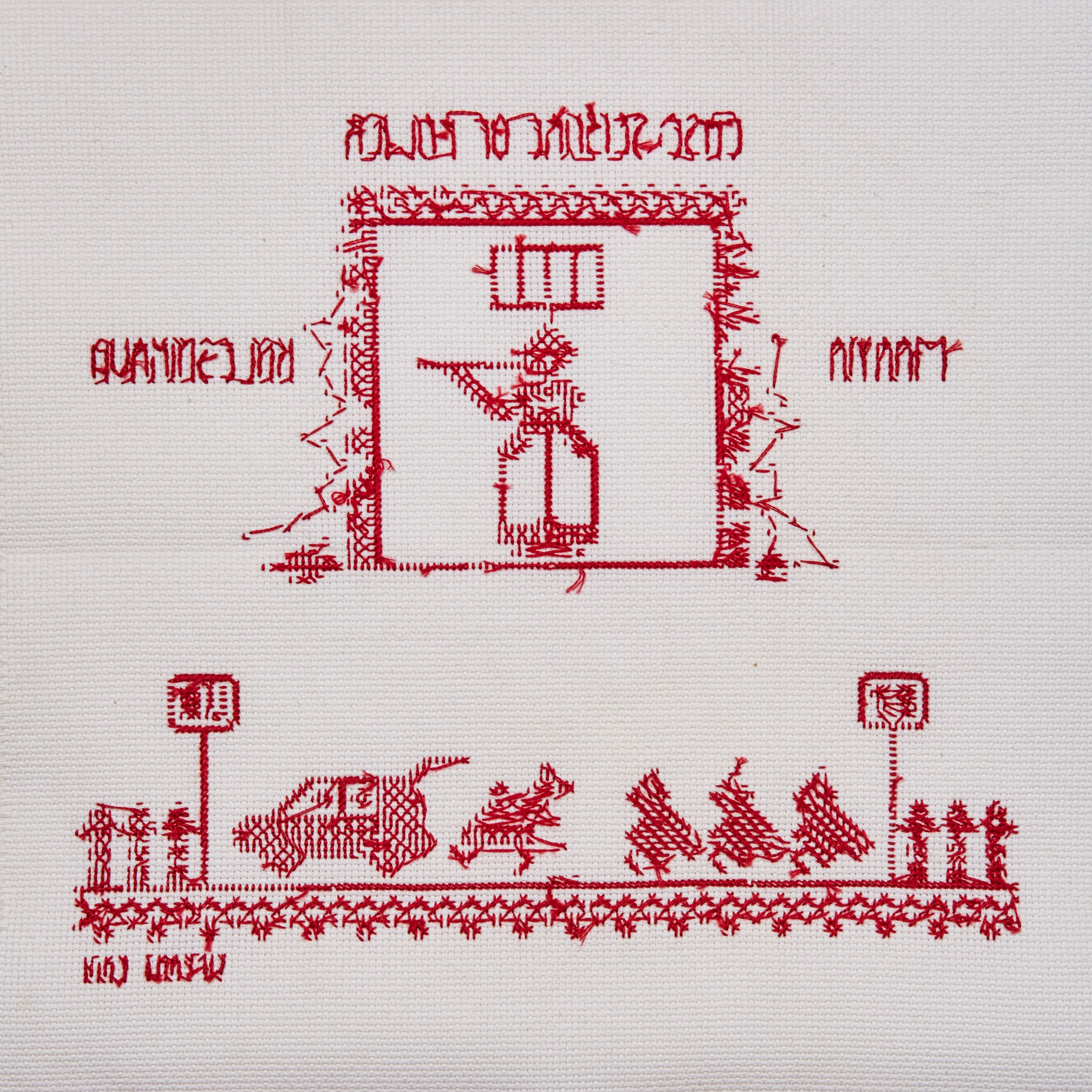

AA: A conversation on the extinction of minority languages, prompted by Anton Vidokle and Pelin Tan’s film Gilgamesh: She Who Saw the Deep (2022), most of which is in Kurdish, and which is accompanied by a “timeline of suppressed languages” compiled by Olga Olina, Hallie Ayres, and Vidokle), reflected on the importance of preserving other ways of thinking and being. How can the internationalized, increasingly anglophone field of contemporary art contribute to a situation in which different languages and cultures co-exist, rather than accelerate their marginalization?

iF: It’s an important question. The recent and many attempts to produce works of art and to publish books in the native language of the speakers are the only way to go. Many institutions also recently have begun to give well-attended tours in languages other than English. There are ways, although the lingua franca is English.

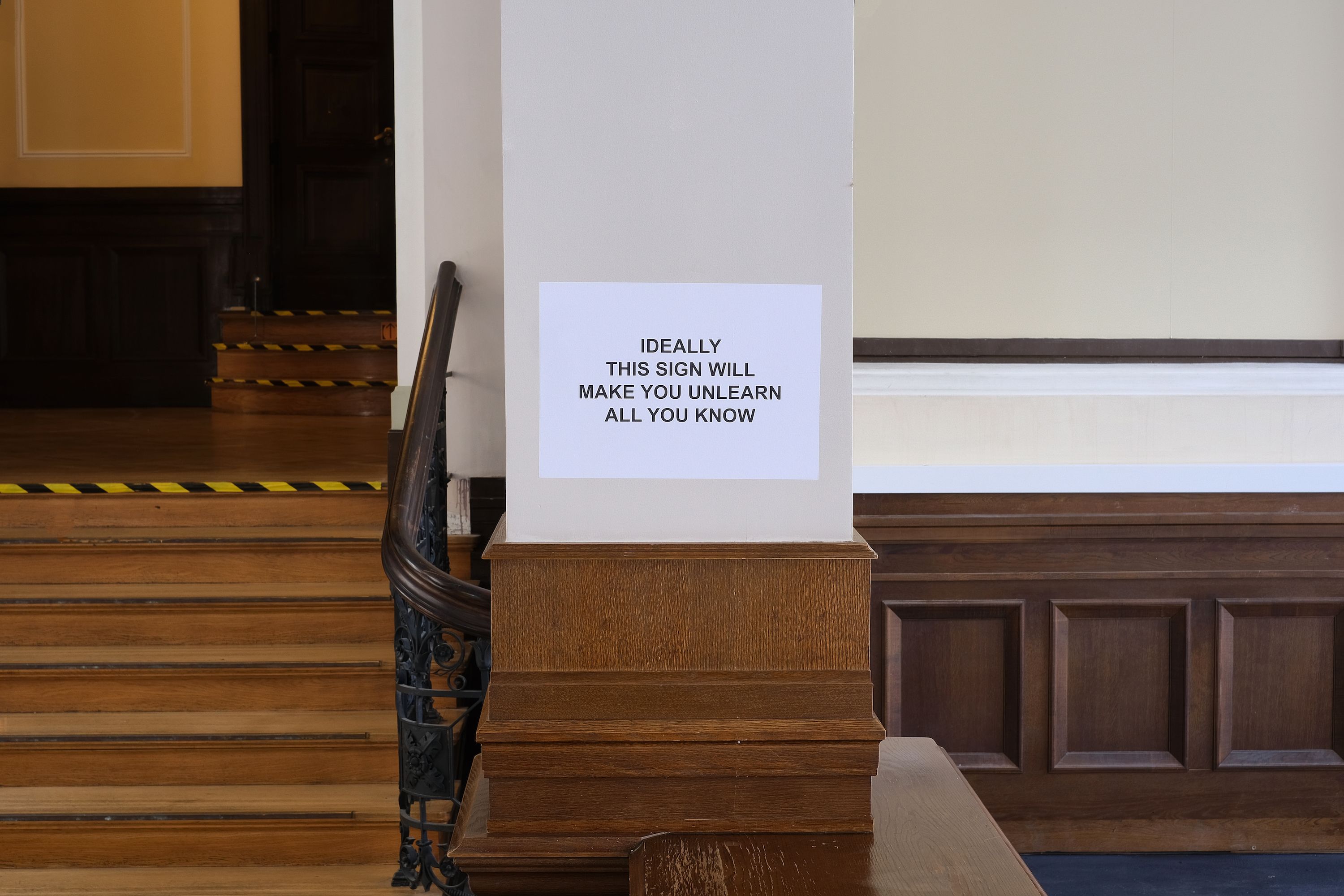

AA: The title is taken from an allegorical poem by Ojārs Vācietis in defense of free speech. Allegory is an historically effective means of evading censorship: do you believe that art can continue to function as a medium for the expression of dissent even when others have been closed down?

iF: Absolutely, since art can be—and very often is—allegorical and not literal. And possibly allegory is the only way to continue to practice and perform dissent while under authoritarianism. Democracy allows us the luxury of direct critique, which is perhaps not practiced as often as I would like. But allegory as a form of survival is interesting beyond exhibition making, as an effective form for operating under oppressive or authoritarian power structures. But going back to the poem, I must say that I was surprised that the then-Soviet censorship mechanism allowed the poem of Vācietis to exist! It is not that allegorical in how it ends:

The little bird must be caught,

So we can fill our tummies.

After singing his little heart out,

He’ll go straight to the tabby.

I am brimming over

After a hearty meal,

A tomcat with red whiskers

Stretched out at my heel.

The “red” tomcat is a bit too obvious, no?

AA: One of the things that is so striking about the show is how frequently affect is figured as an instrument of resistance. I’m thinking now of Maryam Tafakory’s video works, even more powerful now in the context of what’s happening in Iran, and Erica Scourti’s installation, both of which are driven by emotions that cannot be contained by authoritarian structures (patriarchal, religious, socio-economic), that spill out and over their frames, that are ungovernable. How important is it that art, in the current climate, works at this emotional and embodied level, not only appealing to our reason?

iF: Very, very important, although I feel that it is not so much emotionality as a less sterile, more lyrical description of the conundrum which we are in: be it the exhausted turbo-capitalist body, or the censored and repressed body, especially the female one.

But I find it interesting that you describe it as a spill-out. For me, the affect of it is more like a spillover—the term used by epidemiologists when a virus jumps from one species to the next—because it is a narrative that mutates from one work to the next. The natural human response that makes it possible to survive authoritarianism and turbo-capitalism has turned us into more docile subjects. So this “ungovernable” that you discuss jumps from one condition of repression or slow violence to another, and then a rupture occurs: the symptoms are no longer hidden or controllable.

Survival Kit 13, “The little bird must be caught,” is on view at Pils iela 23, Riga through October 16. It is supported by LIAA, the state cultural funding body of Latvia.