February 15–April 4, 2024

How might our understanding of education better incorporate communication, participation, and play? And what would be the consequences of that expanded approach? Such questions have been at the center of Amalia Pica’s work for many years, drawing partially on her early experience as a primary school teacher. Her first solo exhibition in New York attends to the manifold aspects of learning across a group of collages, sculptures, and video works organized around a new interactive installation.

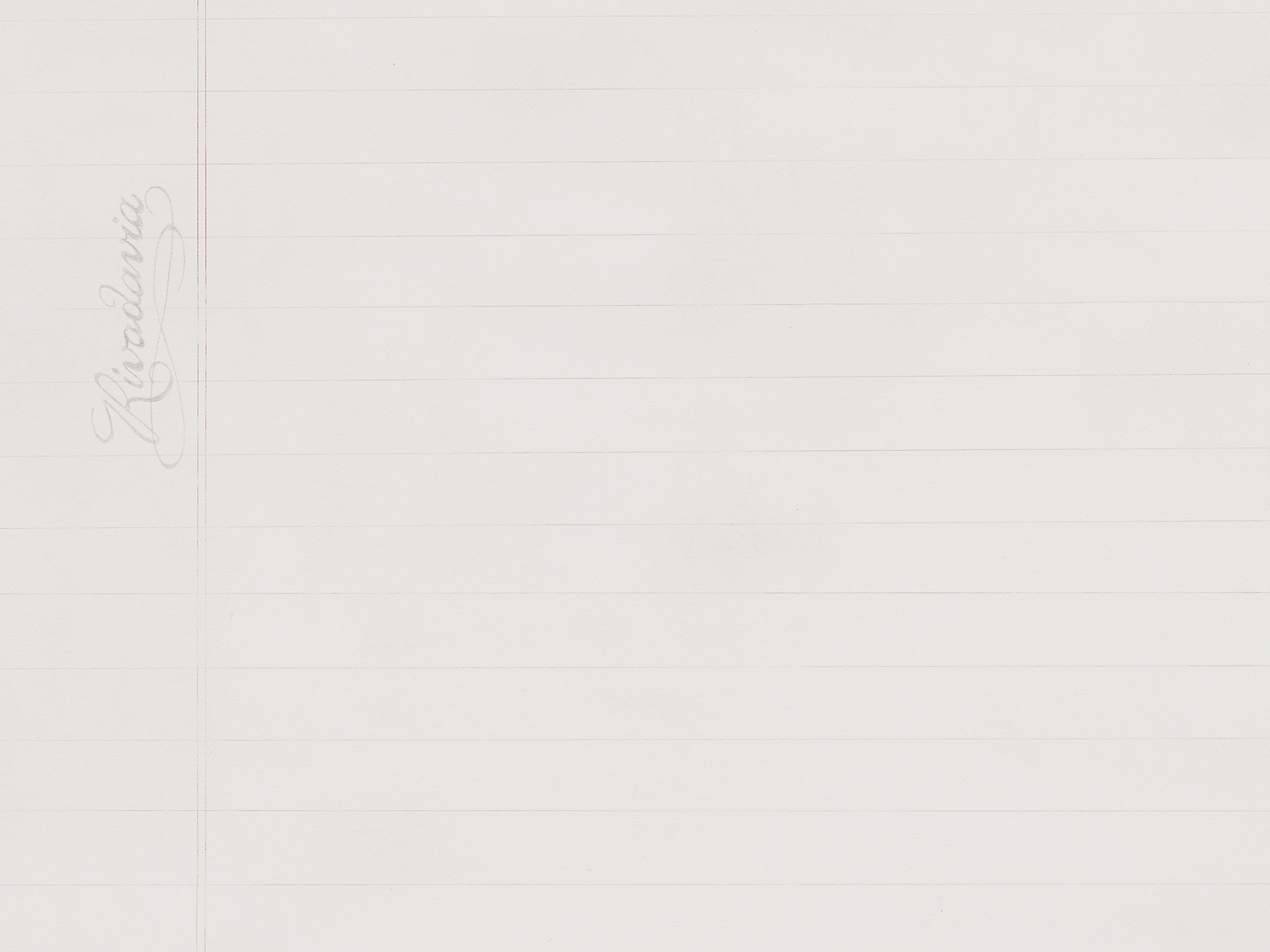

Two understated large-scale graphite and watercolor drawings, School sheets in adjusted scale (or an exercise in how to go back to all the things I hadn’t thought of yet) #1 and #2 (both 2011), are based on notebook paper with “Rivadavia” printed in an elegant cursive in the margin. This references Bernardino Rivadavia, the first president of the London-based artist’s birth country of Argentina, using a font based on his signature. The stamping of state power into the very books in which young people learn how to write signals the reproduction of the ideological subject through a form of repeated inscription. This has chilling implications in the context of the military dictatorship (1976–83) into which Pica was born.

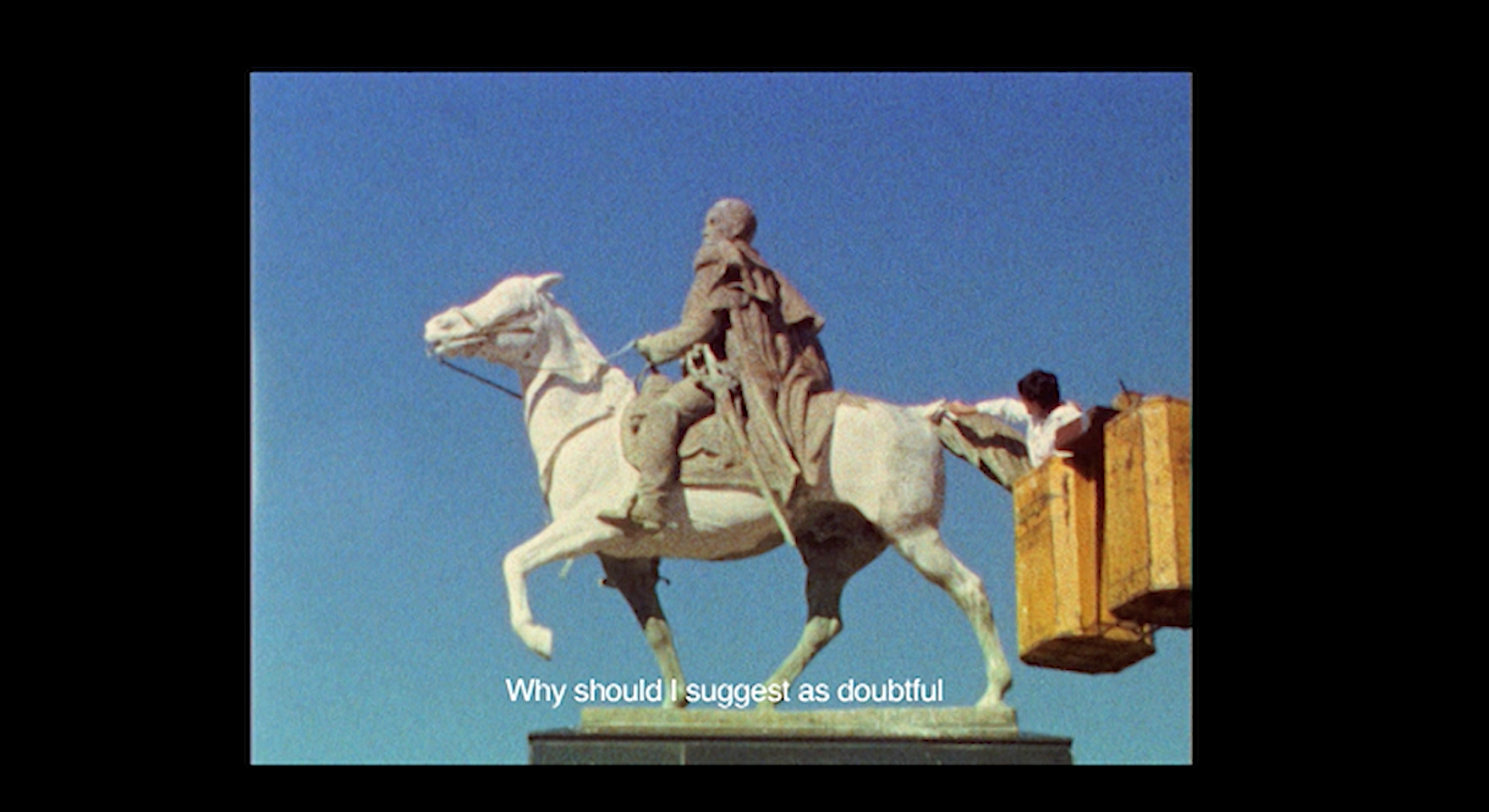

Her 2008 video On Education depicts a public intervention in which the artist painted ten public monuments of men on horses in Montevideo, Uruguay. She used chalk-white on only the horses—a reference to a riddle common in South America and elsewhere about the color of a general’s white horse—and, poised atop a yellow bucket truck, wore the white coveralls common in schools when she was a student in Patagonia. This uniform was intended to create an equitable environment in which all students and teachers looked the same. While many artworks have been made that draw on the iconoclastic impulse to tear monuments down, Pica’s highlighting of the horse suggests that myths can be embedded in historical monuments, and the monument itself as a mechanism used by the state to create public artworks as sites of civic learning.

The central work of this exhibition is Aula Grande (outlined). This large installation, dated 2024, reproduces a domestic space in which every surface and object—a table and chairs, pots and pans, a guitar leaning on a couch, book shelves, and a bed—is covered in green chalkboard paint. Viewers are invited to take a piece of colored chalk and draw or write whatever they wish. At the opening, there were multiple allusions to contemporary events, with phrases such as “FREE PALESTINE,” as well as drawn hearts, tic-tac-toe games, and the declaration “FUCK COMMERCE.” When I asked about the limitations of what could be written, both the artist and the gallery said that they wouldn’t tolerate “hate speech.” Although, given the fraught discourse around how that is enforced, it was unclear how such limitations would be determined.

This introduces a question around the ways in which playful participation in this staged environment intersects with criteria for evaluation. Classrooms, after all, are places of judgement regarding good or bad behavior, right or wrong answers, and so on. Pica transposes this onto a domestic space, acknowledging the ways in which the family and the school are both institutions in which such judgements occur. But as an artwork, do we follow Claire Bishop’s advice to establish the rules of the game in socially engaged artworks such as this, thus avoiding what she calls the “standoff between the nonbelievers (aesthetes who reject this work as marginal, misguided, and lacking artistic interest of any kind) and the believers (activists who reject aesthetic questions as synonymous with cultural hierarchy and the market)”?1 Or is it, like Pawel Althamer’s Draftsmen’s Congress—an ongoing project initiated at the 2012 Berlin Biennale that invites people to communicate using images in place of words—about ceding authorship to an amorphous collective?

In the sense that the work raises such questions without providing hard answers, Pica might here be thought of as the “teacher” inviting the audience to be “students” participating in a classroom exercise whose aim is to cultivate the skills that make collectivity possible. Another question arises. Is the work better understood in the space of representation, where the school and the family are invoked as sites of learning in negotiation with the freedom of the subject, rather than the sphere of the real? If so, that would suggest that, when something is deemed to be inappropriate, and is subsequently erased by the “authority” of the artist/teacher, or the overarching power of the gallery, it is part of this negotiation—given that the work allows erased phrases to be rewritten. (Where I teach, by way of example, there is an ongoing cat-and-mouse game in which students write “free Palestine” around campus, which prompts the university administration to erase them, only for the cycle to be repeated again and again.) Such erasures can be read as acts of censorship, but they here invite repeated provocations and counter-responses. Seen this way, the wiping-out of an inflammatory phrase chalked on the wall of Pica’s installation is not outside of the work but a crucial component of its representation of education as a battlefield.2

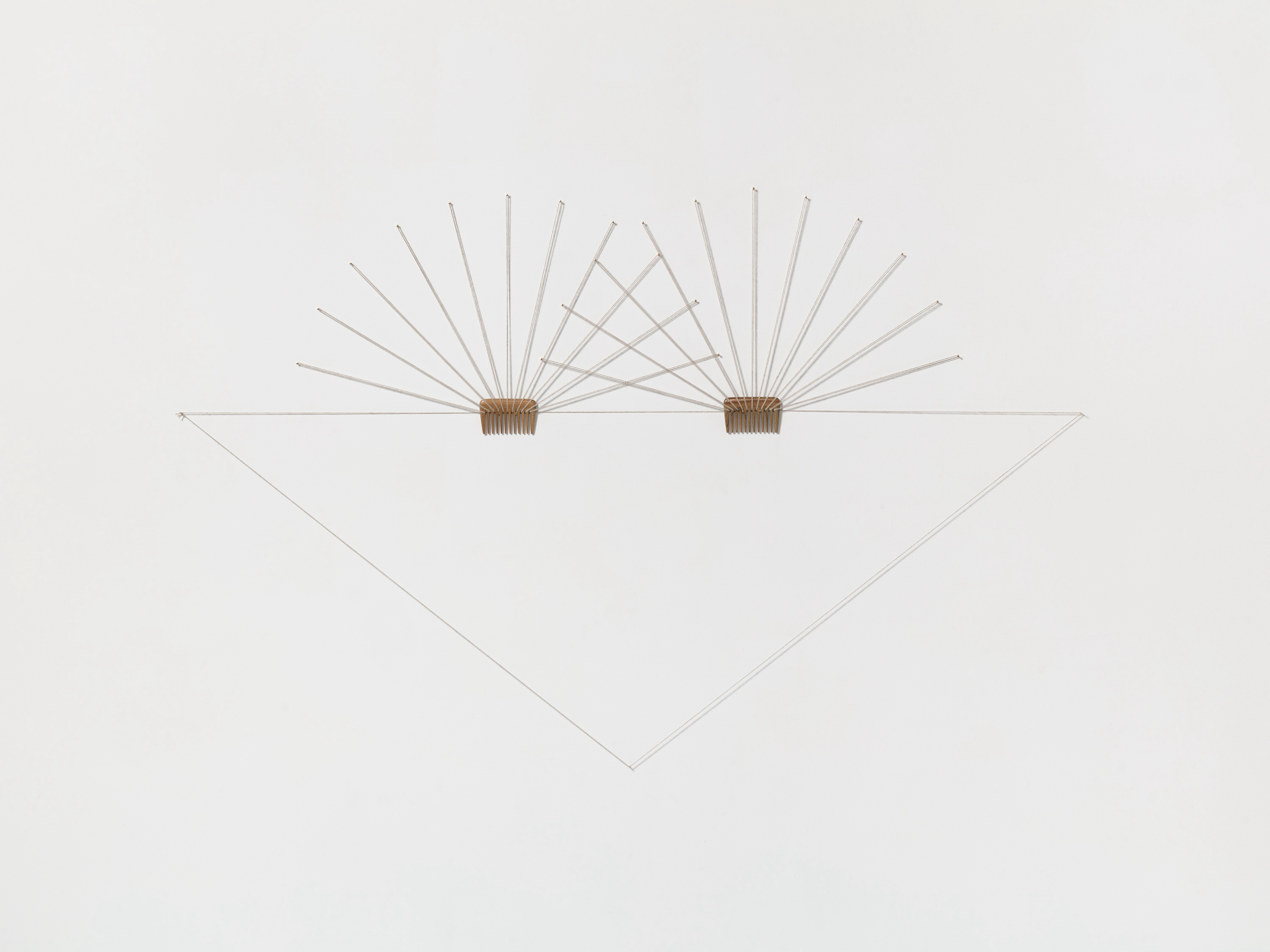

The exhibition also includes a series of collages and sculptures that center on catachresis, here considered as a rhetorical misapplication of terms to given objects that produce double images, such as “a head of cabbage” or a “comb’s teeth.” It also includes sculptures and paintings connected to forms of image-making dating from early childhood; some are based on drawings by the artist’s son. They are abstract and the basic building blocks of manifesting visual meaning. Combined, these four bodies of work, all made in the last couple of years, are less about education as an ideological structure than the mechanisms of meaning-making. Pica’s works interrogate how we learn cultural conventions of visual and verbal language—learning as a cognitive function rather than an institutional one.

See Claire Bishop’s “The Social Turn: Collaboration and its Discontents,” Artforum (February 2006), https://www.artforum.com/features/the-social-turn-collaboration-and-its-discontents-173361/.

A recent example of this would be ruangrupa’s documenta 15, the radical gesture of which, lost amidst the accusations of antisemitism and ensuing debates, was not only its collectivism but also the ways in which participatory forms of education were privileged, such as the transformation of the Fridericianum to “Fridskul.”