March 16–June 30, 2024

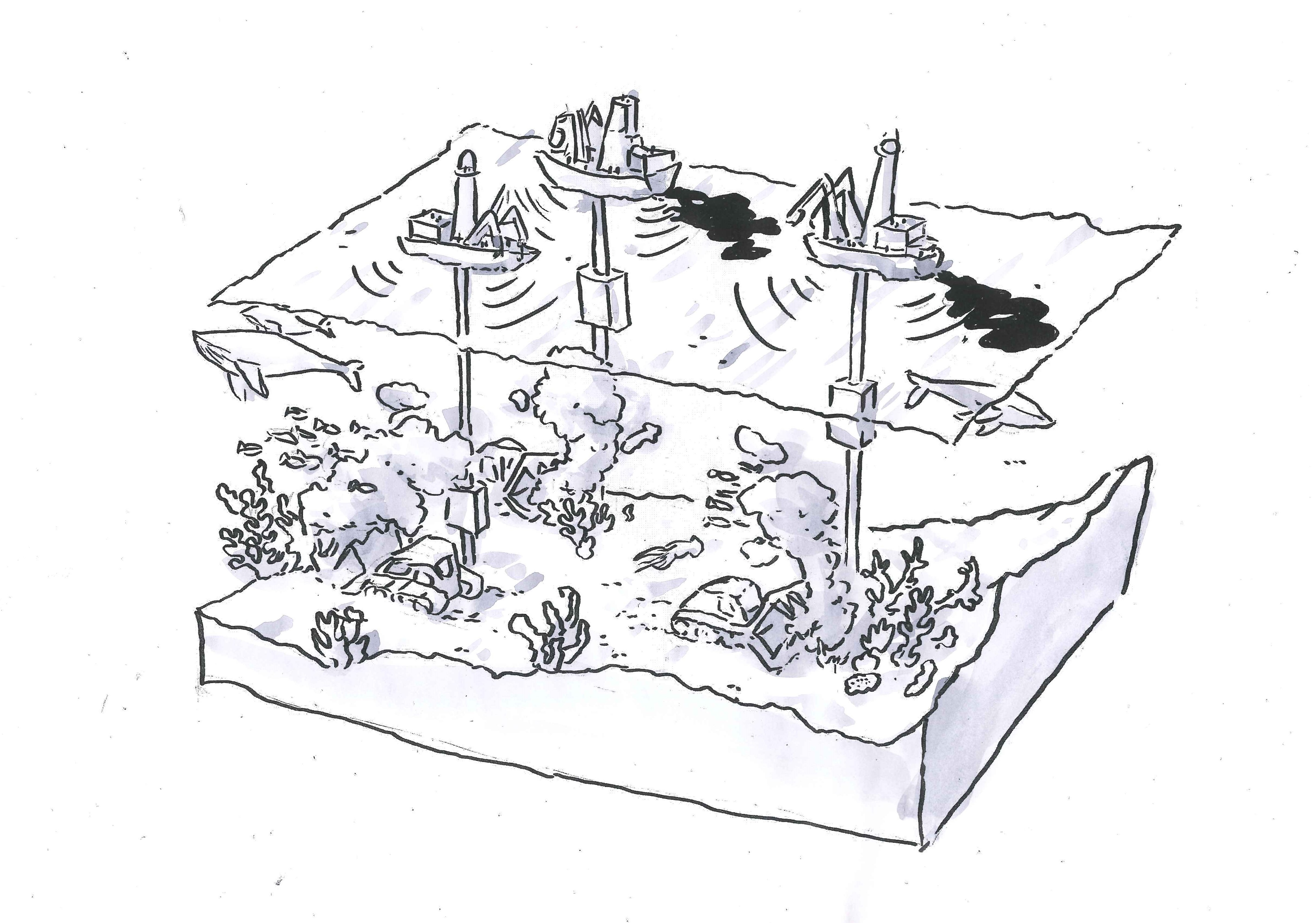

Drawing connections between botany and colonial conquest through the model of the botanical garden, this exhibition reflects on the migration of materials, ideas, and cultures through case studies of eight plant species found in Southern Yunnan: cinchona, horsfieldia, konjac, nutmeg, rhododendron, rubber, tobacco, and turmeric. Artworks are positioned like roadblocks in this large, ex-industrial white cube, so that the visitor must meander around them and, like these migratory species, chart unpredictable courses.

At the entrance, a TV screen supported by two metal poles shows mosquitos drawing blood from human skin, then copulating. Isadora Neves Marques’s hyper-realistic digital animation Aedes aegypti (2017) depicts, as the exhibition text explains, a particular type of mosquito subject to genetic modification by biotechnology company Oxitec. To combat the diffusion of malaria (traditionally treated by quinine derived from cinchona), a “self-limiting” gene is injected into male mosquitos, meaning that their offspring don’t survive into adulthood. An alternative antidote is disclosed on the wall behind the viewer: a botanical illustration of quinine from the Illustrated Manual of Chinese Trees and Shrubs (1937), printed in blue.

A trail of black particles leads across the floor to a metal trolley marked with letters in Mandarin “勘界” (Boundary Survey), repeated twice. Closer inspection of the trail reveals the particles to be Sichuan peppercorns. Looking around, I find two other identical trolleys with the same phrase in Mandarin and different languages: Ethiopian (loaded with white sesame), and Hindi (turmeric). Three trolleys form the Guerrilla Squad (2018) by Liu Xinyi, the lines of which seem to divide and map the gallery while the aromas of the spices spread throughout the space. The resulting blend of aromas, in contrast to the boundary-like visual quality of the lines themselves, speaks to tensions visible throughout this exhibition: between boundaries and exchange, Indigeneity and extraction.

Bordered by the peppercorn, The Rice Wall 03 (2024) is an eloquent gesture of self-defeat: Tant Yunshu Zhong’s floor sculpture is an arrangement of green and beige rubber sacks, filled with rice and its husk, arranged in a circle. This combination of materials refers to the 1952 Rubber-Rice Pact, effective till this day, overseeing China’s export of rice to Sri Lanka in exchange for rubber. In Zhong’s version, the former is embraced by the latter, like husk to crop, transgressing the concept of boundary in a closed loop: intimacy in trade mimicking that found in nature.

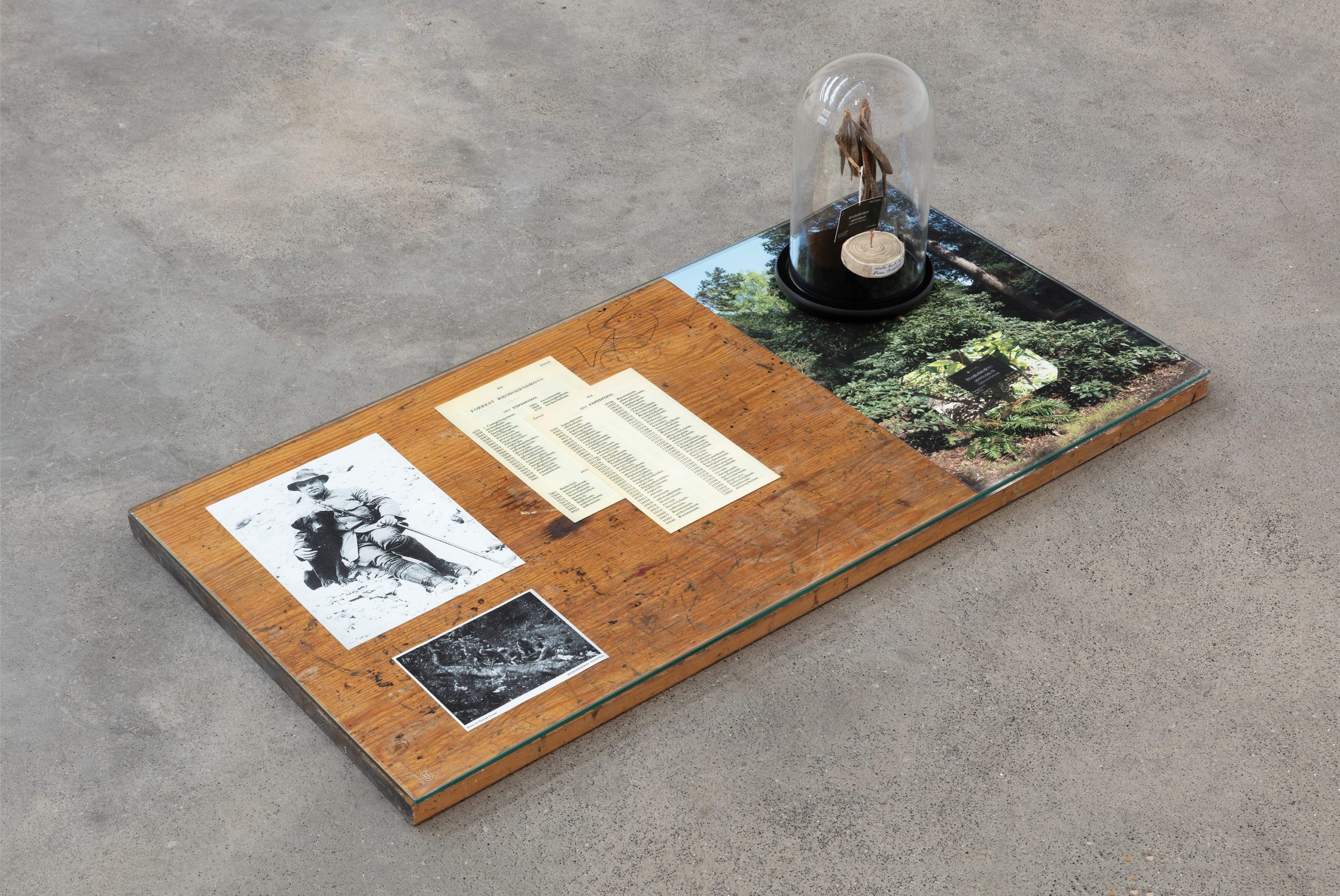

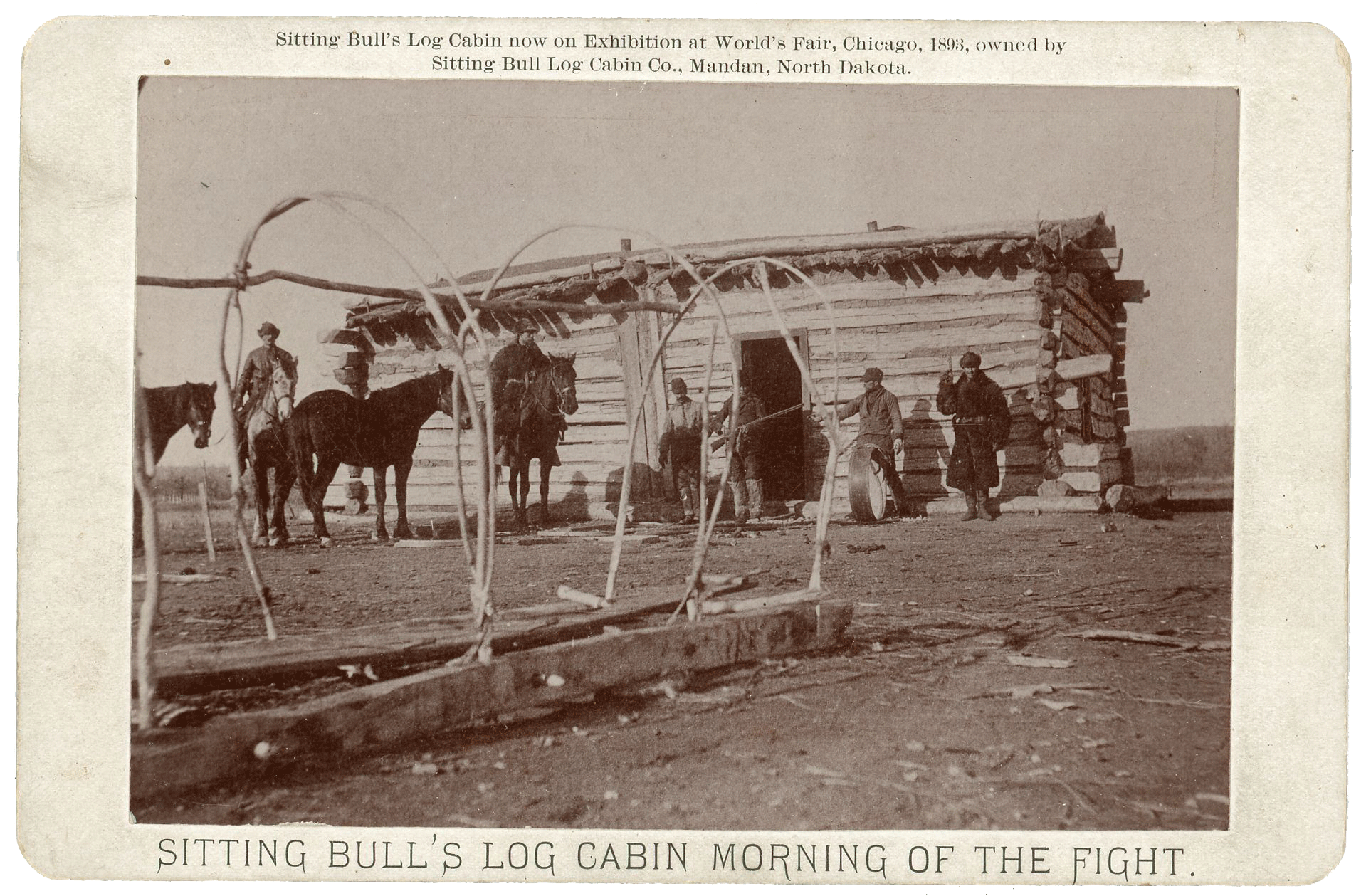

In Liu Yu’s documentary Caecus creaturae (2019), the artist hunts down the seventeenth-century figure of Georg Eberhard Rumphius, a blind botanist employed by the Dutch East India Company, in the Maluku Islands of Indonesia. Through an assemblage of archival illustrations and island landscapes, Liu interweaves historical biographies of Rumphius with interviews with locals. Cheng Xinhao’s Re-stole (2019/24) displays a specimen of a branch Cheng stole from the earliest rhododendron planted in the Royal Botanic Gardens Edinburgh, right next to the man who first brought it from Yunnan to England: the aptly named Scottish plant hunter George Forrest.

In many ways, the works in this exhibition bring to mind “the ethnographic turn” identified by Hal Foster in the nineties, among others, as well as the Foucauldian lament of “anthropologization.”1 In lieu of labels, gray posters printed with botanical illustrations—designed by Pianpian He and Max Harvey—occupy the walls, adjacent to their referred works. These drawings are unaccompanied by any textual identification until the end of the exhibition, where their edited “biographies” are collaged in a large colored, annotated poster near the exit. By positioning plants as “expeditionary,” rather than as migratory, or simply subject to global trade, curator Dai Xiyun repositions a traditional object of study as a subject. The eight plant species in this exhibition could be thought of as informants, offering clues to the nature of China’s interactions with the world, as well as pointing to the consequences and conditions of these histories of circulation.

See Hal Foster, The Return of the Real: The Avant-Garde at the End of the Century (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1996), 171–204; and this quote: “‘Anthropologization’ is the great internal threat to knowledge in our day” from Michel Foucault, The Order of Things (New York: Vintage Books, 1994), 348.