REDCAT, Roy and Edna Disney CalArts Theater, Los Angeles

April 5–August 31, 2025

“It’s not easy being green,” composer Holland Andrews sings to the packed auditorium. Nearby, performer Katrina Reid, costumed in an astronaut helmet, spins slowly with a collapsible reflector, casting iridescent light across the chroma key–green stage. “Having to spend each day the color of the leaves,” Andrews continues, “when I think it could be nicer being red, or yellow, or gold—something much more colorful like that.”

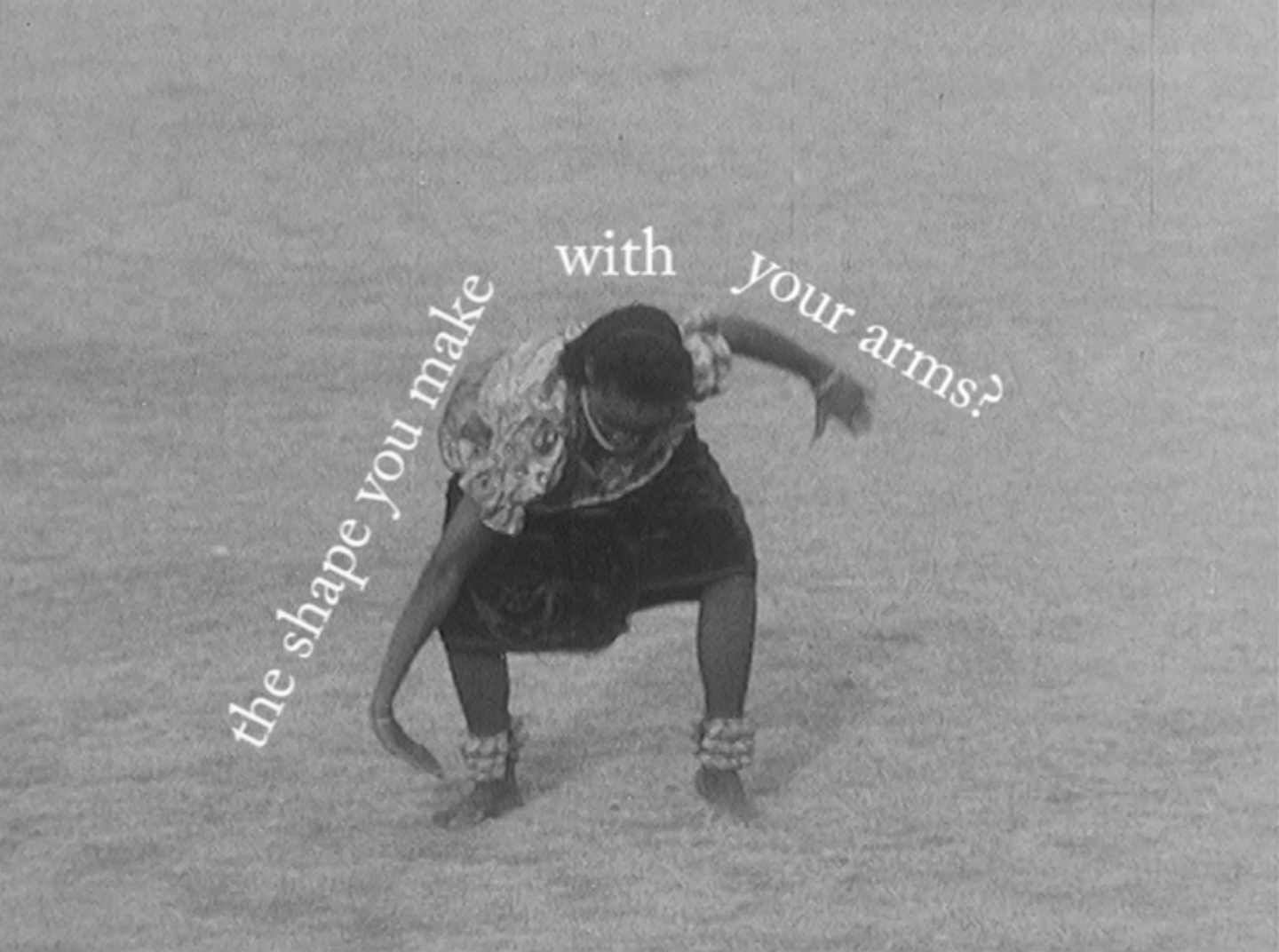

In [siccer] (2023), a live performance at REDCAT accompanied by an interdisciplinary installation at ICA LA, artist and choreographer Will Rawls uses the voice and body to explore how Blackness resists capture in spaces historically designed to erase it. In both the performance and exhibition, five (sometimes six) dancers are caught in a stop-motion photo shoot. They evade the amplified shutter clicks of an ever-present camera, poised atop a tripod facing the green screen backdrop. Through Andrews’s sonic interventions, chroma key staging, and disruptions of genre, [siccer] dismantles the media apparatuses that seek to render Blackness visible, legible, and consumable.

The song that Andrews sings, “It’s Not Easy Bein’ Green,” was originally performed in 1970 by Jim Henson, voicing Kermit the Frog on Sesame Street. Rawls has cited a 1975 performance of the song by Ray Charles and Henson on The Cher Show, in which their duet meditates on the politics of Black visibility and self-acceptance, as a reference in shaping the work. In a public talk, Rawls reflected, “In that episode, the color green becomes the blues.”1

The mood suddenly shifts as performers shout, “It’s a twister!” while spinning to Andrews’s surreal beat of cow moos and thunderclaps. “Where’s genre?” one asks. They begin describing it as “opalescent, iridescent, smedium [sic], French,” before turning playfully self-aware. “Is it genre or is it cake? What about genre-futurism? Do we need to Get Out?” Genre becomes a shimmering, unstable, and ever-shifting protagonist in its own right, both sought after and satirized. Each performer’s internal monologue pokes holes in the rules of containment. Rather than adopt genre’s familiar labels—afrofuturism, Black horror, performance art—the performers destabilize them, stepping in, stepping out, and dismantling as they go.

Andrews’s hauntingly beautiful soundscape—layering recordings of swamp critters, echoing cries, and melodic club beats—imbues the performance with more gravity. The voice becomes a radical tool of fugitivity by evading both transcription and narrative coherence. The performance can be read through the lens of Black performance theory, particularly the writing of Fred Moten and Saidiya Hartman. By collapsing the distance between spectacle and spectator, it stages what Moten in In the Break (2003), building on Hartman, calls the “economy of hypervisibility.”

Where Hartman examines how Black life is rendered hypervisible through objectification, Moten focuses on how Black performance resists this bind, insisting that “objects can and do resist.”2 He draws on Frederick Douglass’s retelling of his Aunt Hester’s scream as a moment of sonic rupture that resists discipline, objectification, and the demand to be legible.3 In [siccer], Rawls extends the lineage, considering how the voice and sonic soundscapes move beyond limitations of language. Even the title gestures towards this rupture, riffing on the Latin sic, meaning “thus” and used by editors to disavow responsibility (as above) for nonstandard usage, and signaling tension between Black vernacular and standard English forms.4

At ICA LA, [siccer] spawns in the main gallery, transformed into Georgia’s Okefenokee Swamp, with cattails sprouting from the floor.5 Four video channels play a rendition of the live performance, featuring the same ensemble of five performers, their images veiled by a suspended field of semi-transparent green panels. Bodies glitch, morph, and blend depending on the viewer’s angle, generating fragmented moments that resist framing. While the live performance at REDCAT enacts fugitivity through movement, voice, and rupture, its museum counterpart grapples with the impossibility of preserving performance through time, especially one designed to evade capture, risking the very containment it critiques. Instead, Rawls leans into this contradiction, transforming ephemerality into a space of unresolved tension and ongoing dialogue. The installation invites viewers to move through a space suspended in post-production, where the body resists the institution’s impulse to fix, frame, and flatten time.

In a climactic moment, absent from the exhibition but central to the performance, the performers pull Rawls out from behind the curtain, revealing him as the Wizard behind the spectacle. Here, Rawls is both choreographer and performer, exposing the mechanics of the production and rupturing the illusion of authorship and control. The gesture transforms the green screen from a site of deferred post-production into a live instrument for reimagining conventions of race, authorship, and identity in real time. What Rawls offers across his iterations of [siccer] is not a complete narrative or fixed meaning, but a rehearsal of refusal—one that resists resolution and remains insistently in process.

See Jim Henson and Ray Charles sing “Bein’ Green” on The Cher Show, 1975, posted September 24, 2011 by Christopher Jones, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cTxG7n4Xzws; and “Open House Art Talk: Will Rawls: siccer,” artist talk presented at ICA LA, April 10, 2025, posted April 11, 2025 by ICA LA (Institute of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles), Youtube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XsnW04QPHFw.

Fred Moten, “Resistance of the Object,” in In the Break: The Aesthetics of the Black Radical Tradition (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2003), 1–24.

Moten, “Resistance of the Object.”

siccer, REDCAT press release, 2025.

“Open House Art Talk: Will Rawls: siccer,” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XsnW04QPHFw.