April 24–August 3, 2025

Hidden away in a corner of Candida Alvarez’s first museum retrospective is an invitation to a 1980 open studio program at New York’s PS1 Contemporary Art Center (now MoMA PS1). Presumably made to be photocopied and distributed, it consists of a photograph taped to a sheet of paper alongside handwritten dates and subway directions to the event. The mysterious photo shows what looks like a painted cloth suspended in a corner of PS1 amid pipes and cinderblocks—perhaps a provisional installation by the artist. This invitation vividly conjures an artist who for decades has made sensitive, shifting work near the heart of the “art world” and in dialogue with its central players, yet somehow did not receive the level of attention achieved by many of her peers.

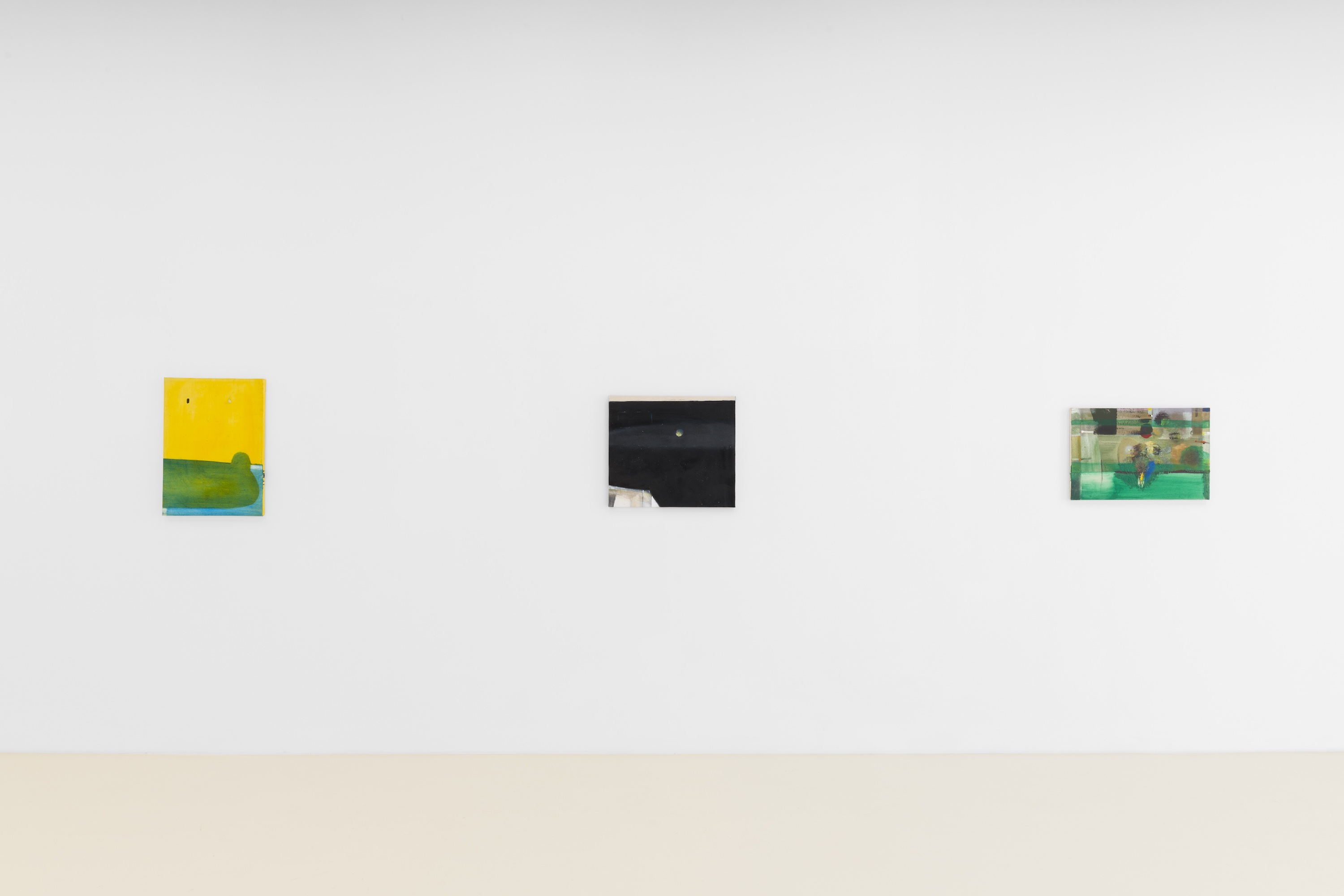

Presented at El Museo del Barrio, where the artist worked as a curator in the 1970s, the exhibition’s loose chronology weaves Alvarez’s artmaking and biography in a manner consistent with her own approach. Alvarez grew up as a child of Puerto Rican immigrants in Brooklyn and spent her formative years as an artist in the city, before leaving to pursue educational and teaching opportunities in Connecticut and Chicago. Although most often described as a painter, Alvarez has consistently resisted a signature technique or style, freely absorbing influences and strategies throughout her career and repurposing them to create mixed-media works that reflect her experiences as a Puerto Rican woman, mother, and artist. Structured around Alvarez’s navigation of different life stages and predominantly white and male art spaces, the exhibition suggests that the fluidity and adaptability of Alvarez’s work are its most radical elements.

The earliest paintings, collages, and multi-panel installations in the exhibition show Alvarez redirecting the art discourses of the 1980s to address memories from her upbringing. In the large canvas She Went Round and Round (1984), a Catholic schoolgirl is depicted spinning with her arms outstretched in an apartment living room, surrounded by family photos, domestic furnishings, and a dog. The gestural style seemingly takes cues from the decade’s Neo-expressionism, while the heavily worked surface suggests the influence of Jack Whitten, who was Alvarez’s teacher at Fordham University. In Soy (I Am) Boricua (1989), Alvarez uses a diptych format to demonstrate the double consciousness that was central to her Nuyorican identity. Playing with abstraction and figuration, the discordant colors and styles of the stacked panels clash dramatically; at the same time, together they evoke a two-story apartment building with a solitary female figure looking out of an upper window. In interviews, Alvarez often says that she first learned to see the world as an artist through the window of her childhood apartment in Brooklyn public housing.

Alvarez’s practice incorporates radically new material approaches in a central gallery devoted to works from the 1990s, which the artist spent in New Haven, eventually enrolling at Yale. Inspired by a faculty that included Mel Bochner and Howardena Pindell to examine the “internal structure of experience,” as she describes, Alvarez experimented with a range of conceptual strategies in tandem with material drawn from Puerto Rican life. The floor installation Wish Me Luck (1997/2025) humorously evokes the labor-intensive holiday ritual of grating root vegetables to make pasteles, accompanied by metal box graters re-cast in glass and a pile of the achiote seeds used to create annatto oil, one of the cornerstones of Puerto Rican cooking. (The importance of pasteles is underscored by the later inclusion of the 2002 video work Celia, which straightforwardly shows her mother preparing them.) On a wall nearby hangs Circle, Point, Hoop (1996), the mystifying object that lends the exhibition its title—a painted wooden circle dotted with nails, which are in turn connected by strings in a numerical pattern seemingly guided by an invisible logic. In this juxtaposition and other works, the exhibition reveals Alvarez grappling with conflicting desires to be both radically self-disclosing and to make works that resist interpretation.

The final gallery presents paintings based on an idiosyncratic vocabulary of color and form, which the artist began to make after moving to Chicago in 1998 to teach at the School of the Art Institute. Although these large-scale works like Claro and Partly Cloudy (both 2023) are abstract, their shapes, colors, and titles are based on personal memories and photos, and often look as if they contain specific, if elusive, imagery drawn from landscape, architecture, or weather. One work contains the words “estoy bien” (“I’m fine”), a phrase the artist says she repeatedly heard while searching for family members after Hurricane Maria devastated the island in 2017. The paintings function for the artist and those with similar frames of reference as a sort of coded language, while the rest of us are left to appreciate their evocative formal qualities: biomorphic patches of vibrant blue and green, punctuated with irregular leaves and shingles of yellow and pink.

With these fluid abstractions, Alvarez finds a meaningful means of expressing the fluidity and abstractness of identity, a concept paradoxically rooted in both visible signifiers and internal truths. A camouflage-patterned wallpaper based on this same vocabulary runs along the central exhibition corridor, along with a variety of works that carry similar patterns in different media. Connecting the artist’s life and career is a visual form designed precisely to abstract, and thereby disguise, while smartly situating questions of visibility, opacity, and perception.