June 4–July 26, 2025

A commercial gallery might seem an unlikely context for the work of Gala Porras-Kim. Over the past decade, the artist has made her name as a practitioner of a particular kind of institutional critique: one that explores, and imagines alternative possibilities for, the relationships between museums and the objects in their collections. Her focus is not the art industry, with its rapid cycles of production and exchange, but rather those places that claim to act as more-or-less permanent stewards of historical and cultural artifacts. Often she works directly with the institutions themselves. It’s a cliché by now to point out that the Latin origin of the word “curator” is “curare,” to care. But what types of care, beyond physical maintenance, do the workers across departments of a museum provide, especially for items (human remains, sacred offerings, the stuff of domestic life, and so on) that were never intended to be preserved there?

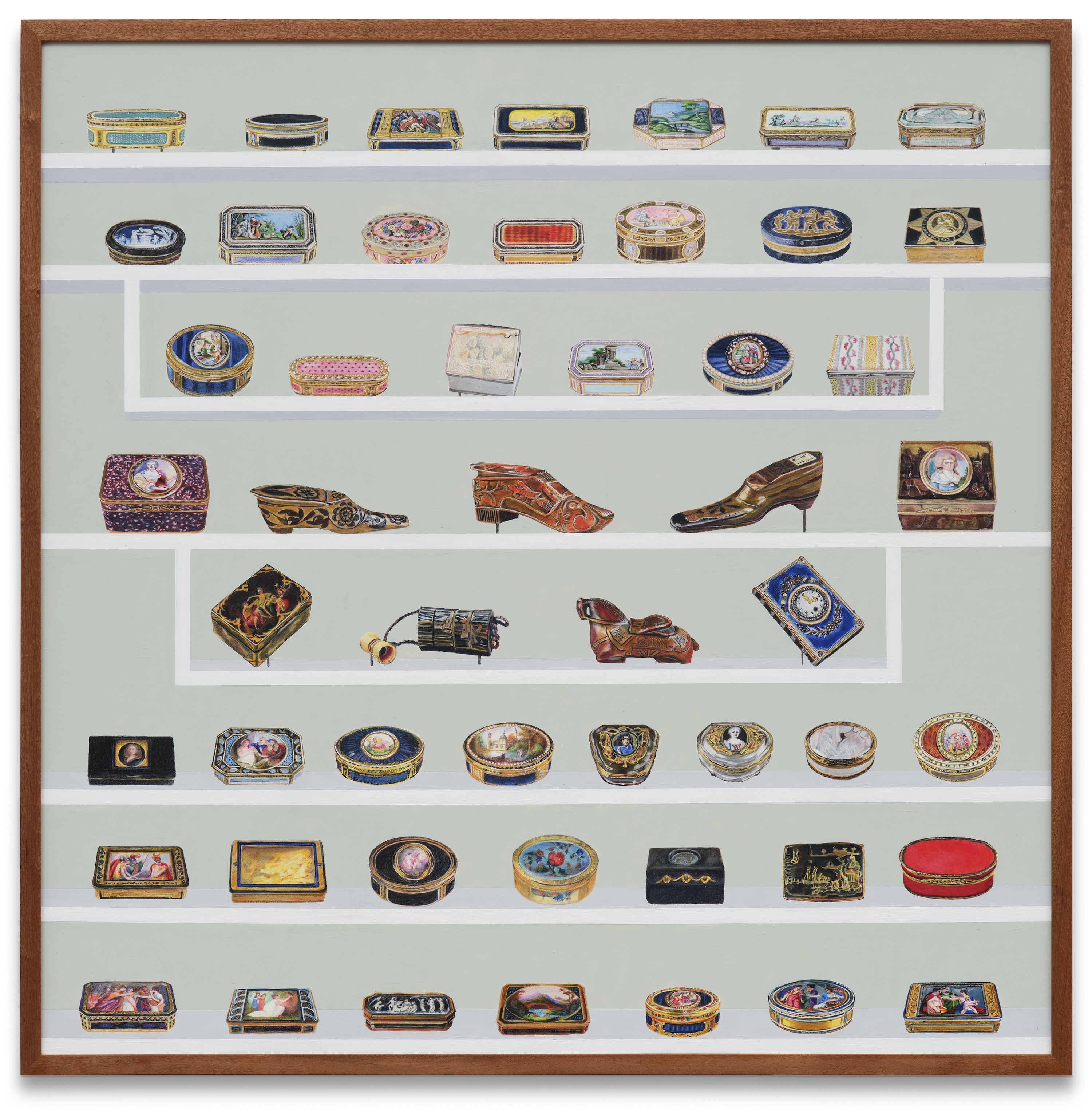

“The categorical bind,” on view across two floors of the elegant Georgian townhouse that is Sprüth Magers’s London space, presents some recent examples of Porras-Kim’s ongoing and inventive engagement with this question. The title refers to the way in which, as she argues, objects are “bound” by the taxonomic systems traditionally used to organize institutional collections. Porras-Kim illustrates her point primarily through what she calls “index drawings”: meticulously detailed, near-photorealistic images in colored pencil or graphite, representing objects either in situ (in vitrines or drawers accompanied by labels, and in some cases literally bound with black-ribbon ties) or as shadowless cut-outs arranged on imaginary white shelves. 69 containers at Carnegie Museum of Art or at Carnegie Museum of Natural History (2025), for example, consists of two separately framed drawings of various plates, vases, bowls, and other vessels—many of them beautifully decorated with painted figures and bright patterns—held in two of the Carnegie museums in Pittsburgh. For no discernible reason, the containers in the top half of the diptych were at some point classified as “art”; those in the bottom half “natural history.” None, of course, are ever used to serve food or drink or to display flowers.

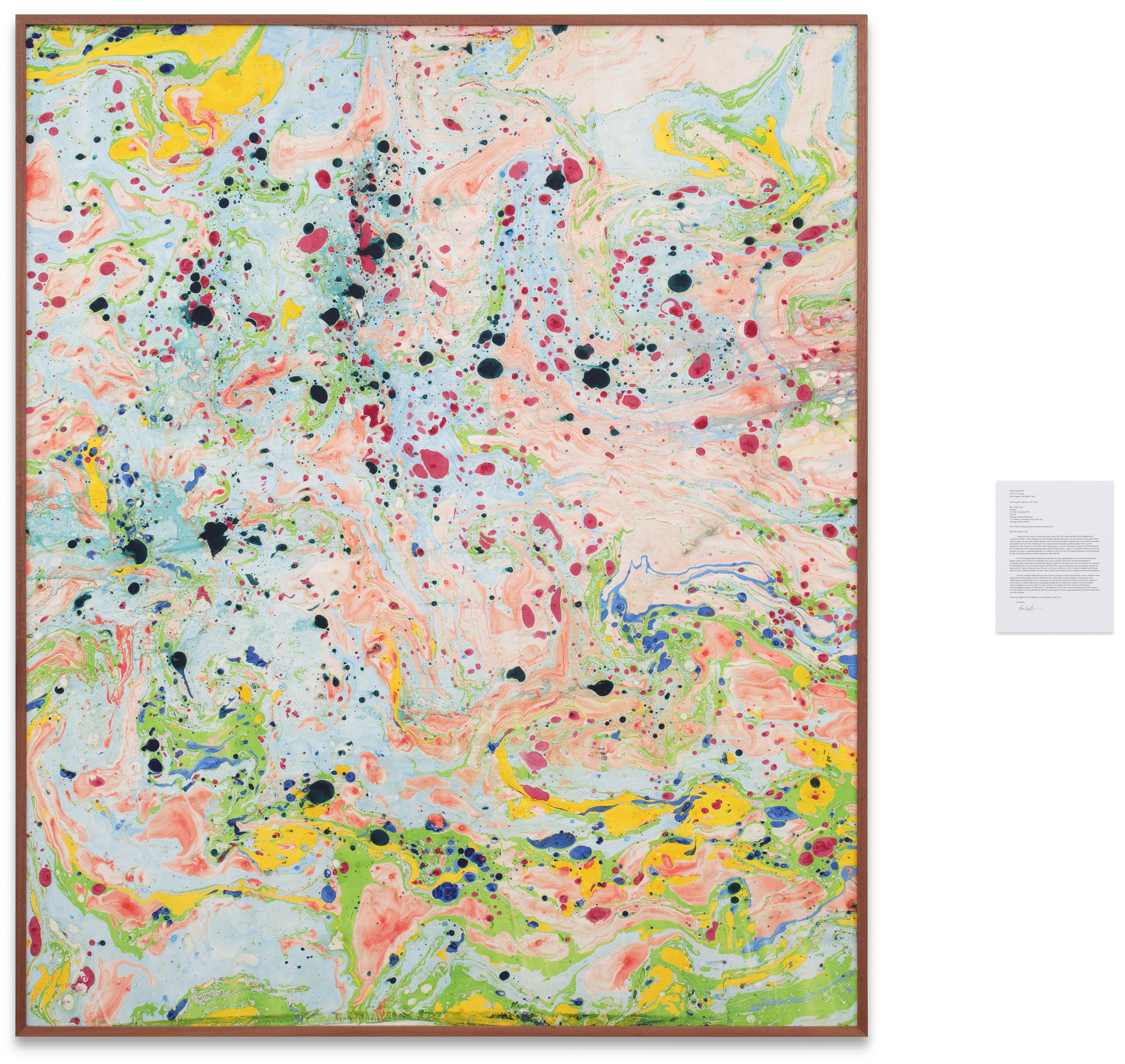

The exhibition also includes a sampling of Porras-Kim’s work in other media, particularly her speculative proposals to museum directors regarding objects in their custody. Leaving the institution through cremation is easier than as a result of a deaccession policy (2021) is titled after the subject line of Porras-Kim’s letter to the director of the National Museum of Brazil, written in the aftermath of a fire that decimated the building and its collections. In the letter, she questions the museum’s decision to reassemble the damaged remains of the oldest human fossil in the collection, referred to as “Luzia.” Displayed alongside is a tissue on which the artist placed some ashes from the fire in the shape of a handprint. This tissue, she writes, “might be the closest thing to a cinerary urn to hold [Luzia’s] cremains until you might try to see her personhood, and she stops being merely an object in your collection.” Following a similar logic, A terminal escape from the place that binds us (2025) takes its title from a letter concerning human remains held in the Gwangju National Museum. Since 2021, Porras-Kim has produced a series of marbled paper works in attempts to communicate via necromancy with the spirits of the dead (collectively labeled Sinchangdong43), with the goal of identifying their desired resting place.1 On view is the latest result: pools and swirls of blue, green, red, yellow, white—an indecipherable map.

Given the subject of the show, it is natural to think about how the works on display may also be “bound” by the system in which they’ve been placed—in this case, the commercial art market. You can see why galleries want to work with Porras-Kim, who is unusual in the field of museum critique for producing work that is visually striking and attractive as well as conceptually potent. (Compare her vivid drawings, for instance, to the indexing approach of her former CalArts teacher Michael Asher: a printed catalog listing all the works deaccessioned by MoMA from 1929 through 1998.) Still, a certain amount of explication is required to make the ideas legible. Her letters to museum directors are one way of doing this. The artwork titles offer further hints. But these are relatively minor gestures to the conventions of museum curation. What happens when you take a project about institutional stewardship and put it up for sale—especially when it looks so, well, sellable?

Take Burial Chamber Scene (2025): a large square piece of paper, 72 by 72 inches, covered all over with strokes of dark graphite. Porras-Kim has imagined that space where the dead, and any objects buried with them, were meant to be forever sealed from view. Understood in its context, the work is an effective statement on the right to disappear into obscurity. And yet, looking at this work framed on the white-painted wall of a gallery designed to emulate the tasteful interiors of a rich collector’s home, I began to wonder whether it might be mistaken for something else: a bland specimen of the once-popular brand of abstraction known as Zombie Formalism—a derivative spin on Malevich’s Black Square (1915), perhaps. Of course, you can’t blame an artist for wanting to make a living from their work. But art, too, requires more than physical care to survive.

The remains are from multiple bodies found on a first-century BC shipwreck. See “Should Human Remains Be Kept in Museums? Artist’s Work Reflects Original Resting Places,” South China Morning Post, November 19, 2023, https://www.scmp.com/lifestyle/arts-culture/article/3241930/should-human-remains-be-kept-museums-artists-work-reflects-original-resting-places.