A handsome, besuited young man strolls through a sleek high-rise apartment.

“Make the impossible possible.”

Out the window, the city lights twinkle. A seductive female voice asks:

“Do you want to live here?”

[buzzer]

“HELL NO YOU CAN’T!”

“Don’t be an asshole,” BLOCC advises. “Be part of the alternative. It’s already here.”

One observer might think of Bern as a hub for contemporary art in Europe; another may see a sleepy government town. Both are correct to some extent. In Switzerland, it is mockingly called the capital village, and though the city center is dominated by grand fin de siècle federal office buildings and the trappings of high-level international bureaucracy, it lacks drama or verve. Yet it was in Bern that Harald Szeemann came to fame, and the shock waves caused by the 1969 exhibition “When Attitudes Become Form,” his last at the Kunsthalle Bern, make even more sense given the context from which it burst forth. A bijou neoclassical building, the Kunsthalle sits across from the Hotel Bellevue Palace, the casino, and other grand edifices of buttoned-up Bern, the Aare River meandering far below them. (Back in ‘69, outraged Bernese heaped manure on the Kunsthalle’s entrance and threatened to drive a truck through the front door.) Bern has been in the art news of late thanks to Cornelius Gurlitt’s bequest of his collection of works the Nazis deemed degenerate to the city’s Kunstmuseum. Issues of provenance and institutional responsibility are being worked through painstakingly—and openly—in collaboration with many other organizations, notably the Deutsches Zentrum Kulturgutverluste (German Lost Art Foundation). The authority and stability that make Bern a suitable home for a historically important collection, however, can also be a millstone around the neck of a city that many in the art world would like to revivify.

But there is another Bern: a city with an enviably equipped art school, the Hochschule der Künste, and audiences keen to support the performing and visual arts. It is a city of collective action, exemplified by the PROGR cultural complex, saved from redevelopment in recent years and today host to a thriving biotope with umpteen inhabitants, including nonprofits, universities, and commercial entities. In addition to Szeemann, supposedly sleepy Bern has welcomed the likes of Friedrich Dürrenmatt, Walter Benjamin, Sigmar Polke, and Meret Oppenheim. In this Bern, one will find the Zentrum Paul Klee, a 2005 Renzo Piano building of glass waves that echoes the rolling fields around it on the city’s edge. Named after the pioneering Swiss artist, the Zentrum is an outwardly flashy counterpart to its sister institution, the magisterial Kunstmuseum. Beginning in 2006, the Zentrum continued the Bernese tradition of playing host to itinerant (and exceptional) artists and theorists from far and wide through the Sommerakademie Paul Klee. But times change, and after eleven years of intensive two-week workshops each summer, the Sommerakademie was radically restructured in 2017. A visit to Bern midway through the newly launched program, under the direction of Tirdad Zolghadr, revealed impressive innovation in artistic collaboration and education.

The idea of a summer school first emerged from the Zentrum Paul Klee around 2002. By 2006 a generous sponsor, the Berner Kantonalbank, was secured to finance eleven years of the summer school, then officially called the Sommerakademie im Zentrum Paul Klee. The format was, initially, novel, inviting twelve young artists to congregate in Bern for a program organized by a stellar curator or artist. The list of participants is jaw-dropping: That first year, the curators who defined the program and worked directly with the fellows were Marina Warner, Diedrich Diederichsen, and Laura Hoptman; subsequent years involved Jan Verwoert, Pipilotti Rist, Marta Kuzma, Hassan Khan, and Thomas Hirschhorn. The speakers they invited were equally noteworthy. Which young fellows (artists, curators, and writers) took part in the first iteration of the Sommerakademie? Cory Arcangel, Thea Djordjadze, Tris Vonna-Michell, Ivan Morison and Heather Peak, Agnieszka Kurant, Kemang Wa Lehulere, Filipa Ramos, Shana Moulton, Alexander Provan, Mika Rottenberg, Crack Rodriguez, and Martine Syms, and their Swiss colleagues Nic Hess, Sabina Lang and Daniel Baumann, San Keller, Pamela Rosenkranz, Uriel Orlow, Shirana Shahbazi, Florian Graf, and Francisco Sierra, among many others. In short, it was a spectacular annual program of concentrated intellectual glamour further enhanced by the numerous former curators and fellows flown in to this under-the-radar city to observe each session. Undoubtedly, its effects resonated thereafter in countless collaborations and projects, but ultimately this was a high-octane, hit-and-run program.

In 2016 that era (and the bank’s sponsorship) came to an end. Hirschhorn closed the program on a high note: a packed series of lectures that occupied the Kunsthalle Bern for eight days. Organizers were left to consider whether a Sommerakademie was worth maintaining. How had the summer school landscape changed in the intervening period? By now there were many similar programs the world over. Did a prestige project leave enough of a trace in the city and its institutions? Could a more rooted engagement in Bern generate stimulating symbioses? Zolghadr, who was Sommerakademie curator in 2009, was invited to hash out a proposal. Looking at various existing models, including the Strelka Institute in Moscow, he came up with a concept for a school that would push the limits of short, concentrated convening and tested this idea at the Hochschule der Künste Bern HKB with Suhail Malik and Gabriëlle Schleijpen. And so, in 2017, the Sommerakademie Paul Klee was reborn: a cooperation between the HKB and the Zentrum Paul Klee supported by Swiss Mobiliar, the Ernst and Olga Gubler-Hablützel Foundation, the Dr. Georg and Josi Guggenheim Foundation, the canton of Vaud, and private donors.

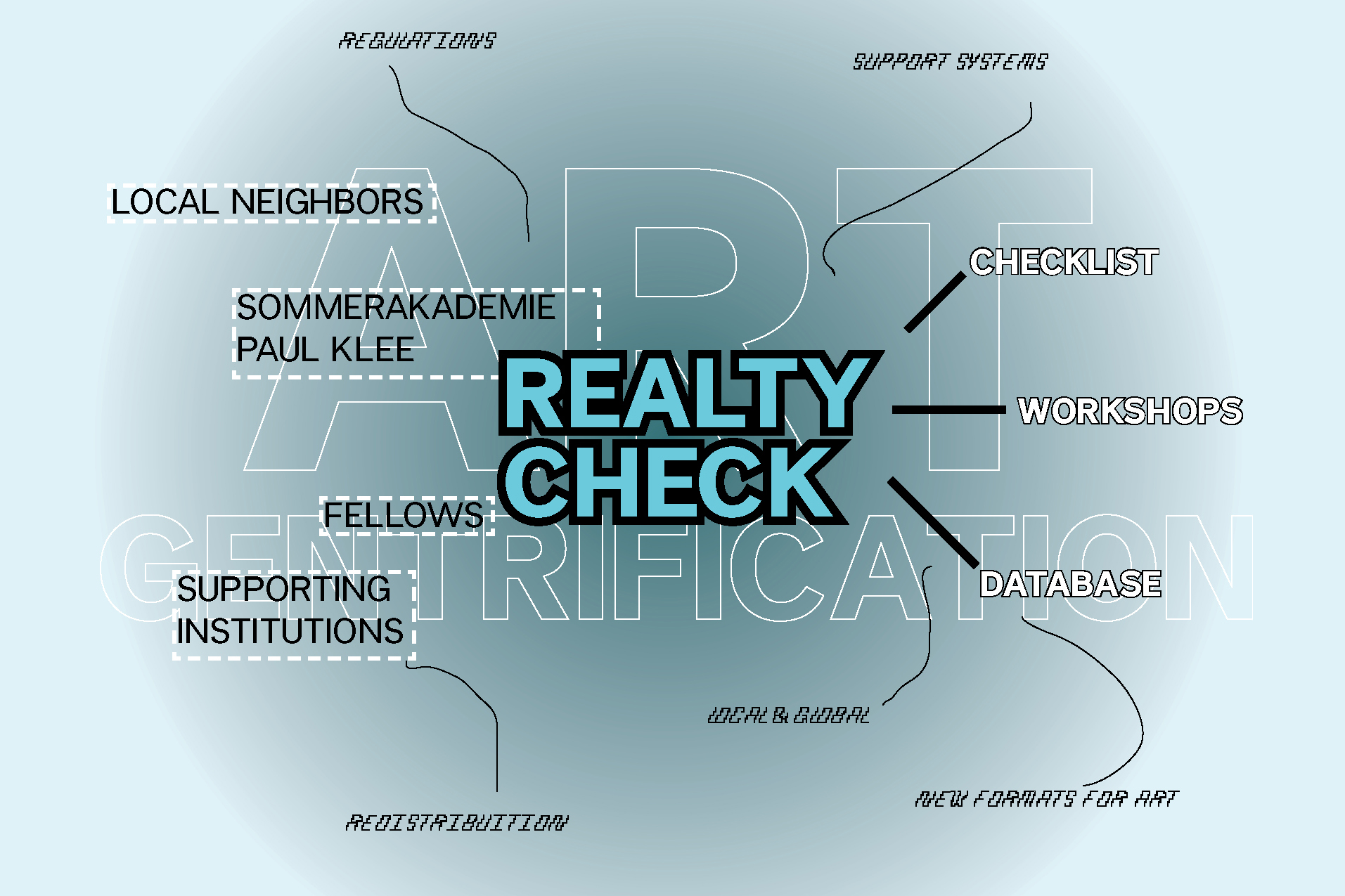

Zolghadr is artistic director and leader of the first cycle. It’s no longer a single-hit session—fellows are instead engaged for three periods of seven to eight weeks spread over approximately twenty months. A fundamental principle of the Sommerakademie is sustainable collaboration in the development of built-to-last intellectual relationships in what Zolghadr calls “an amnesiac world.” The summer school remains a generous proposition, with travel and accommodation in Bern fully covered, as well as a production budget and access to the HKB’s media and production facilities. Postgraduate (or equivalent) practitioners respond to the published theme and apply online; a long list of candidates selected by a jury are invited to Bern for interviews. Alumni of the previous Sommerakademie are encouraged to reapply; candidates must be at least proficient artists interested in both social issues and a structural engagement with contemporary art. In 2017, from approximately one hundred and fifty applicants, eight were selected: the minimum number for the Sommerakademie to function. The fellows must demonstrate curiosity and initiative, as the group is invited to cocurate the program as it evolves. To quote the Sommerakademie literature: “Although based on the idea of an academy, the aim is to transcend the blueprint of seminars and tutorials, and to focus on group research and cross-professional coalition building.” And to take art more seriously as an agent with responsibility and potential. Zolghadr’s cycle was based on “realty,” an ongoing project of his that encompasses art and financialization and the competitive nature of urban sites in which artists and art schools are embedded.

That was the theory—how has it played out? The eight fellows who arrived in Bern last year are Johanna Bruckner, Crystal Z Campbell, Luiza Crosman, Alexandros Kyriakatos, Alexis Mitchell, Bahar Noorizadeh, and collaborators Heather M. O’Brien and Jonathan Takahashi. Each has an impressive practice involving art production and education, socially engaged research, and activism. They told me they were drawn to the program by Zolghadr’s proposal and by the list of speakers, as well as by realty, a topic that is particularly meaningful now, in a time of “the MacBook artist” who moves from residency to residency, as Campbell put it, paraphrasing guest speaker Dieter Lesage. A longer temporal horizon, allowing ideas to mature and evolve, was also an appealing factor. The first summer the eight were party to lectures and workshops from Philippe Bischof, Tashy Endres, Adelita Husni-Bey, Lesage, Renzo Martens, Suhail Malik, Enno Schmidt, Lise Soskolne of W.A.G.E., and Leonardo Vilchis. Annaïk Lou Pitteloud took the fellows to cooperative settlements in the city, in addition to hitting the familiar Bernese institutions.

From the get-go in 2017, the eight considered their role in the broadest urban ecosystem. As Campbell said, “Artists are often not the most vulnerable communities, but the question is about how the current framework for contemporary artists assists in the catalyzation of displacement.” Part of the urban framework is the site of the art school—not a neutral space, but one reacting to and sometimes accelerating urban change. The eight were mindful that the Sommerakademie offered them an opportunity to flesh out a complex strategy. At the end of the first summer’s program, the fellows proposed to Zolghadr that they had heard from enough artists—actors approaching realty from other disciplines would be welcome! And indeed, on the recommendation of fellow Crosman, the principals at Rival Strategy (Benedict Singleton and Marta Ferreira de Sá) were invited to Bern this summer, along with researcher Jaya Klara Brekke.

Fast-forward to 2018, and the fellows are no longer strangers but a tight, unusually large, and surprisingly effective group of collaborators. They had been in contact over the past year, as the fellowship requires, but not only that: There have been additional meetings in Berlin, where they were invited to discuss their project at the KW Institute for Contemporary Art, and in Arnhem at the Dutch Art Institute. The Sommerakademie program requires fellows to produce a public outcome in 2019, but rather than this being the cherry on top, in the vein of a thesis project, the fellows have been trying to crack the nut of art education from the start. As part of an ambitious work in progress, they have coined the name BLOCC: Building Leverage over Creative Capitalism. Still in development, BLOCC can be a principle, a strategy, a standard, and a concrete syllabus, but at its core it conceives of artistic education as an agent of change. Whether the fellows retain control of BLOCC or it becomes an open-source platform is one of several details to be nailed down in the months to come.

Though there were just two headline speakers this summer, their visits came amid intense work by the fellows themselves, and the guests’ presentations were fascinating nonetheless. Rival Strategy, a partnership that aims to “democratize strategy,” juggled terms like “apocalyptic strategic imagination,” “openness as a material,” and “skunkworks” while providing insight into contemporary tactics for various organizations of a dizzyingly broad scope and discussing their ethics before leading a closed-door workshop with the fellows. Brekke encouraged the fellows (and later an audience at the Kunsthalle Bern as part of the “Contractual Situations We Live By” program curated by Eric Golo Stone) to think politically about blockchain technology and about how notions like smart contracts, scarcity, economic and mathematical dynamics, trust, and authority translate from the real world to the digital and vice versa. The fellows, in turn, collaborated with the invited speakers on the BLOCC proposal and thought through various ramifications of the concept with them.

BLOCC is more than an idea. As O’Brien wrote to me, the fellows want to “go beyond pointing at problems to finding solutions that build collective leverage in today’s violent, individualistic and careerist art worlds.” Some fellows had already been engaged in teaching at various institutions and now challenge how schools specifically are sites of gentrification. Art schools have responsibilities as neighbors, and as institutions often used in city marketing campaigns, they cannot ignore the complexity of their physical sites and surroundings. Take Zürcher Hochschule der Künste (ZHdK) as an example: In recent years, multiple departments in scattered sites across Zurich were brought into one huge building, a former dairy produce factory called the Toni Areal. There, it is one element of the city’s strategy to redevelop and enliven “Zuri-West,” a formerly industrial sector in an otherwise very dense urban environment. To teach art in contexts such as this, with the art school viewed as some kind of vacuum or blank canvas (like that other construct, the white cube), is an exercise in bad faith. Kyriakatos related to me how he was becoming increasingly aware of his “‘artistic footprint’ in the urban tissue, [his] relation to institutions as a cultural worker.” And BLOCC has already been put into practice with Bruckner bringing Kyriakatos to the ZHdK last spring to jointly teach a seminar on “art and the building,” one of the first BLOCC modules. The hope is that BLOCC heightens awareness among teachers and students of artists’ ability to be ethical and responsible—and to effect change.

As the Sommerakademie’s 2018 session drew to a close, a public reception was held at PROGR. Andreas Vogel, head of the design and fine arts department at the HKB and president of the Association Sommerakademie Paul Klee, thanked the fellows for their involvement. (Nina Zimmer, director of the Kunstmuseum Bern–Zentrum Paul Klee, is vice president.) The admiration was mutual, as several of the fellows told me of their delight in being able to access the art school’s facilities and with the opportunity to teach at the school, a furtherance of the ongoing collaboration between the HKB and the Sommerakademie. Some began last spring and others will follow this year, putting the BLOCC theory into practice. This reflects the HKB’s interest in making a success of—and sustaining—this new Sommerakademie program. Chatting with Vogel and Hans Rudolf Reust, course leader for fine art, it became clear that they found co-running the Sommerakademie a significant, and worthwhile, effort. The Sommerakademie had always focused attention on the city, but this new iteration should bring a more satisfying engagement with the participants. Lasting collaborations are beneficial for the school, particularly with a generation of artists whom students would customarily have less contact with. This becomes all the more pressing given how swiftly artists’ profiles are currently evolving, with many choosing not to fit into an artist’s given role in a post-Fordist economy, favoring instead different, discursive, creative standpoints. Art schools in turn must swiftly develop the tools to prepare would-be artists for these alternative modes. So if the summer school does not fit into an academic mold—no credits are offered, nor degrees granted—it is useful to see, Reust remarked, “how people operate outside rules that have to be followed.”

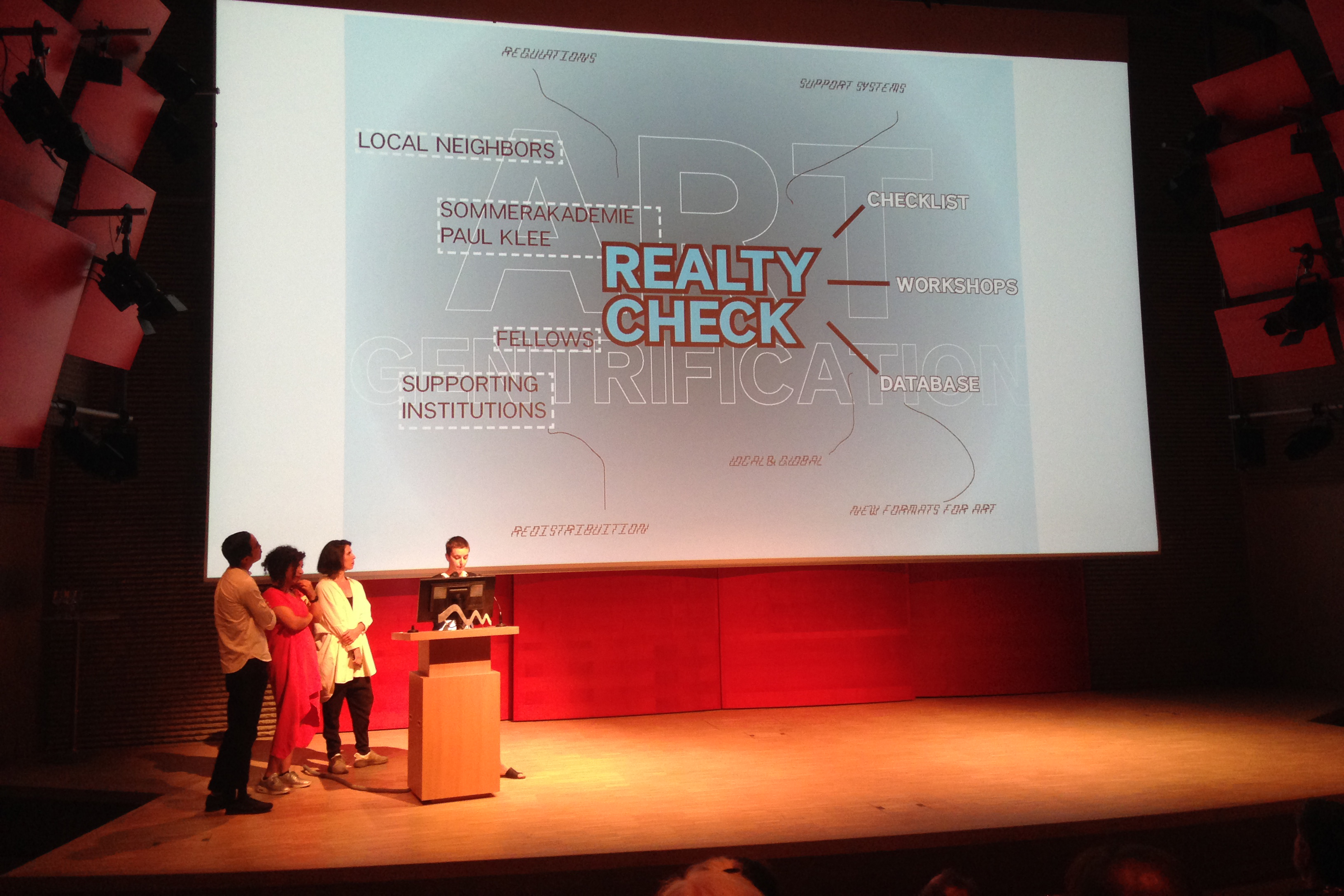

The focus of that closing event was to bring the fellows into direct contact with the public. The BLOCC team savvily interspersed the slick appropriated imagery of its presentation with striking statements—and then explained the heft of the project it is now elaborating. Working in the educational field had not been a preordained outcome, but Noorizadeh related how the fellows had diagnosed a condition: art education’s blind spot to locality. As sites of gentrification, art schools can be generic, so, as Crosman put it, BLOCC teaching could “feed institutions and feed on institutions.” Six modules have been created so far, the titles of which include “artistic footprint,” “beyond pointing,” and “the new arts district.” Though this sounds like a traditional curriculum, it goes further: Modules are designed to equip young artists with conceptual tools to challenge relationships to contemporary capitalism, and these tools are designed to be passed on to students to teach others in turn. More ideas about BLOCC’s organizational dynamics are being teased out, such as how the project might develop virally, or have an inherent scoring or certification system—with the possibility of decertifying an institution being essential—or operate with something like a smart contract. This is where BLOCC stands in October 2018, and the fellows are planning frequent exchanges to develop it further before they officially check out of the Sommerakademie in the spring. Bruckner underlined BLOCC’s urgency afterward: “Teaching is and should always be political, because teaching art should encourage students to position their practice in the contemporary infrastructure of art and challenge how art serves within the geopolitical landscape of international affairs. A strong political body of students, if networked worldwide, might have great impacts on our future.”

As in most places in Europe, summer in Bern was hot, and most fellows mentioned their delight in frequent dips in the broad, turquoise Aare at the end of intense Sommerakademie days. The river flows on unperturbed, past monuments to government bureaucracy, cultural behemoths, and Bern’s burghers. Maybe this Sommerakademie will, like Szeemann’s exhibitions, generate shock waves felt for decades to come in the city. The current fellows will return next spring, and some will teach at the HKB before then, but for now their particular project has gained its own momentum. The cooperation that has been achieved between the eight is extraordinary, and in a way that fits the Sommerakademie’s ethos of stimulating and challenging participants but also allowing for organic developments and fostering resourcefulness. The next Sommerakademie participants and those further in the future are unlikely ever to create something like BLOCC, but the design of the program facilitates their making something equally idiosyncratic with an entirely different approach. And the chances are that as the program continues and new topics are devised by new curators, lasting alliances and partnerships will be forged between artists who are mindful of their duties in society, advocates for art that is responsible to all aspects of its world.

—Aoife Rosenmeyer

Feature

October 11, 2018

Aoife Rosenmeyer

© 2018 e-flux and the author