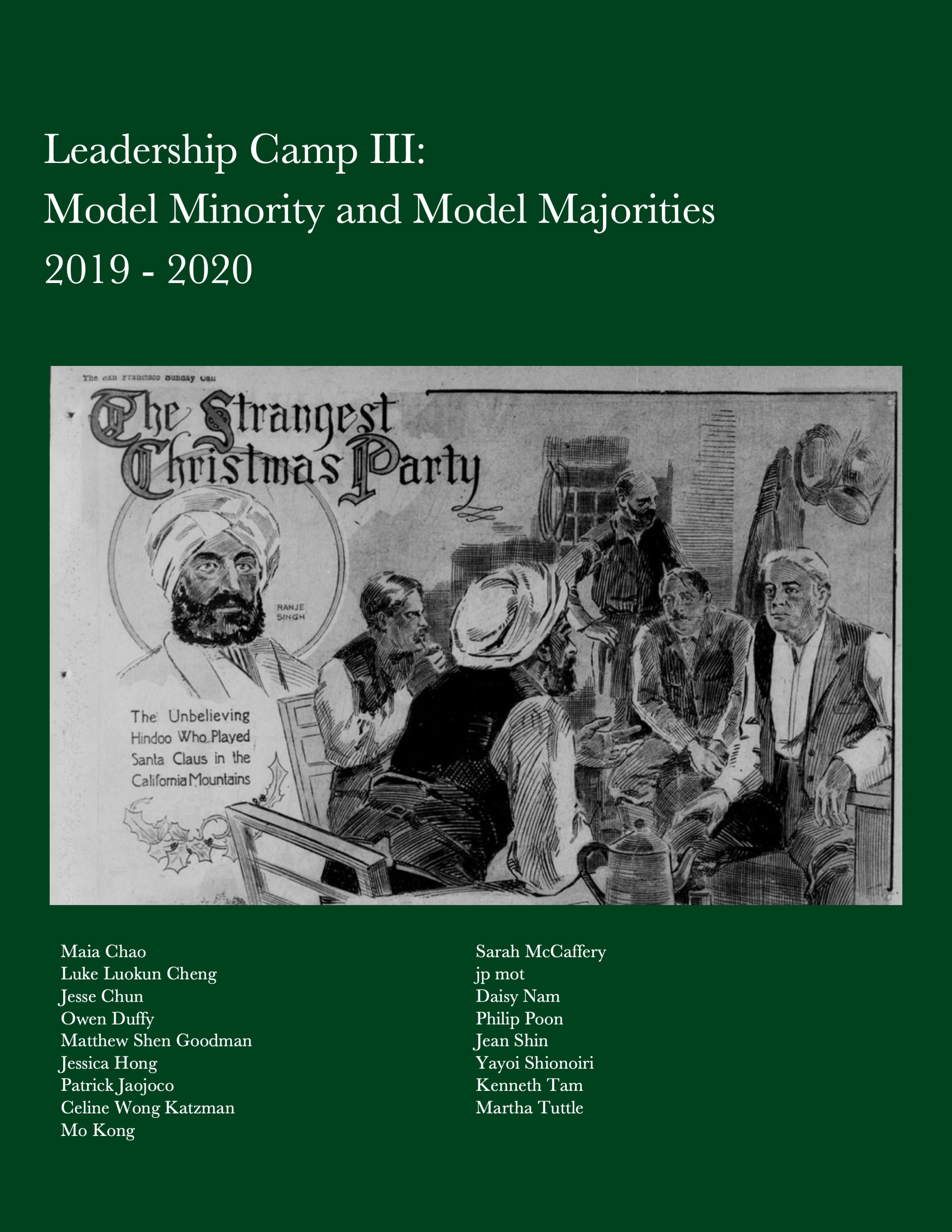

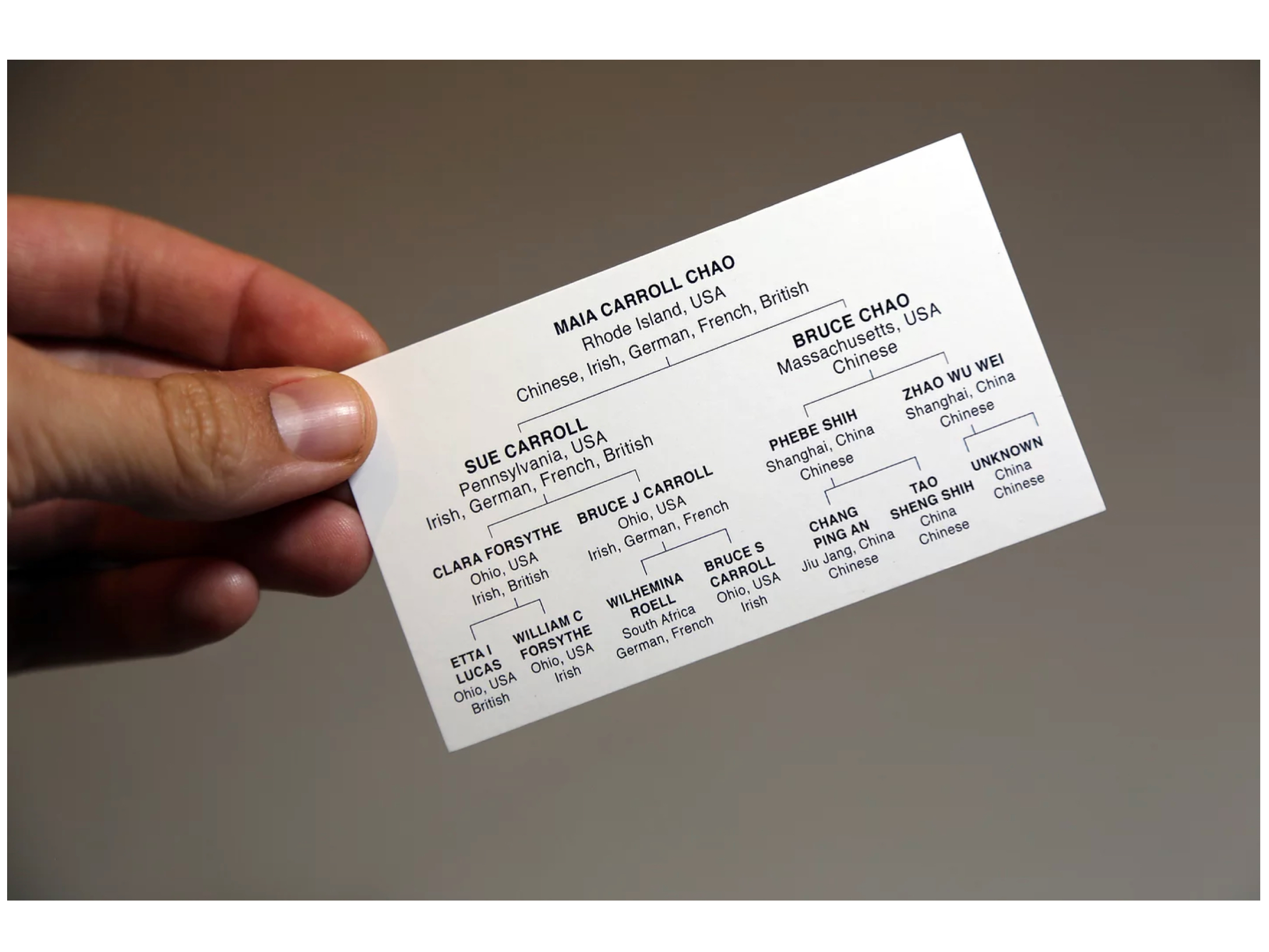

The fourth and final quarterly meeting of “Model Minority and Model Majorities,” the third Leadership Camp organized by Asia Art Archive in America, took an unexpected turn. In the preceding months, we “campers,” a cohort of seventeen artists, curators, writers, designers, and other cultural workers, met for self-guided sessions to discuss and debate the complexities of being Asian in America, the racist history of the term “model minority,” allyship, and nonwhite, non-patriarchal modes of leadership. Halfway through our June 2020 meeting, focused on interethnic community organizing and the history of race relations between Asian and Black communities, the group revisited an earlier proposition: a collectively created asset map. Several campers voiced that discussions of class had been consistently avoided, and after some hesitation, we took the plunge. Artist Maia Chao created a brief Google Form that would populate a spreadsheet of our class secrets (to be deleted soon thereafter), a rarity in an art world in which many perform poverty and gloss over elephantine disparities of wealth. What were our annual incomes? Who among us had inherited wealth? Who was fortunate enough to own their own home in New York’s parasitic rental market? Who enjoyed proximity to the rich? I’ll return to the asset mapping below, but in the spirit of Leadership Camp, let’s be transparent: I am a white, cisgendered male who earns $63,000 per year before taxes, $67,500 if you factor in my adjunct pay. I rent my apartment. My father did not graduate college and has sold cars for almost forty years, but I do have an uncle who married into a wealthy Baltimore family. I possess no inherited wealth, but in case of catastrophe, I do have a safety net.

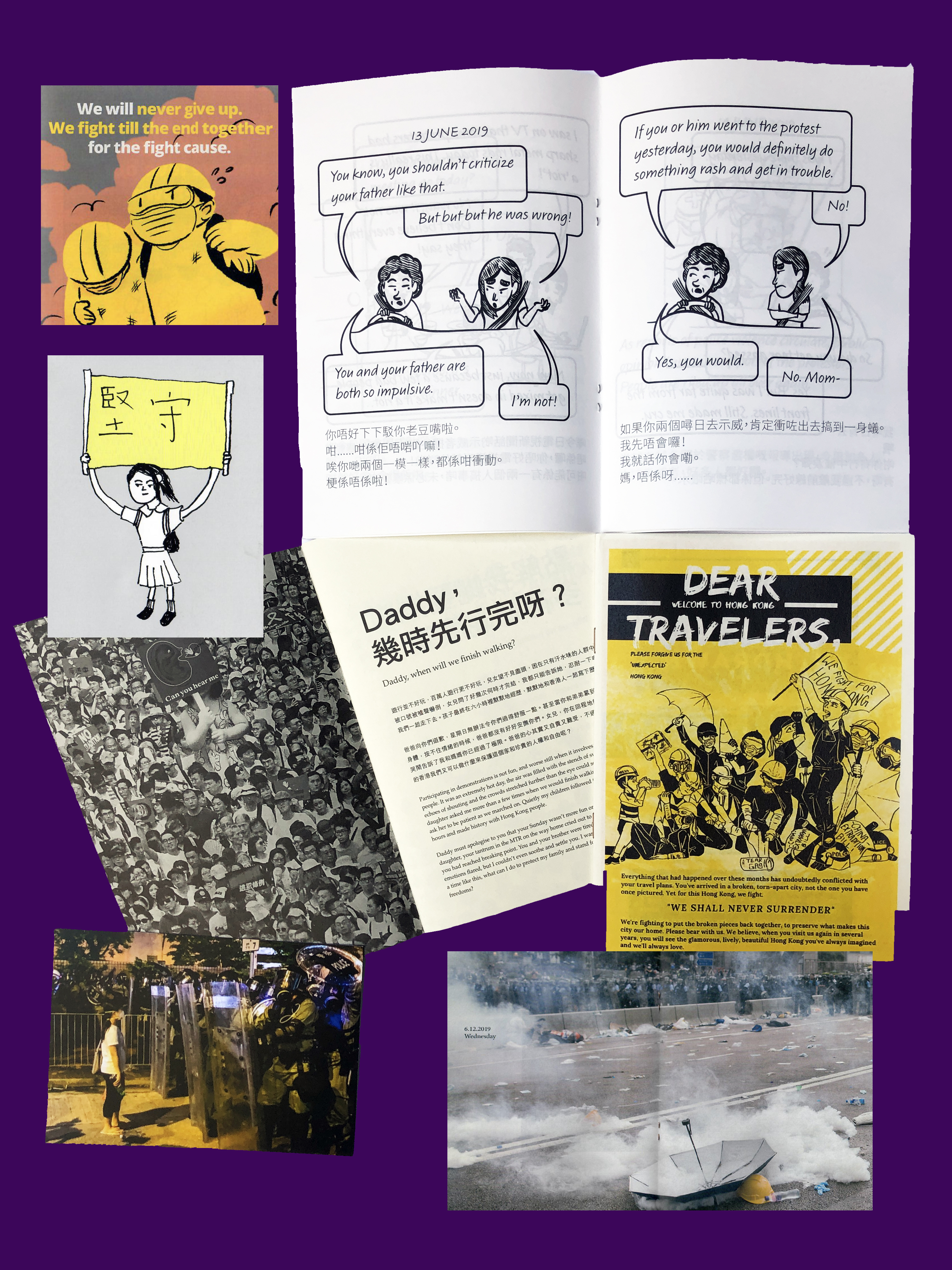

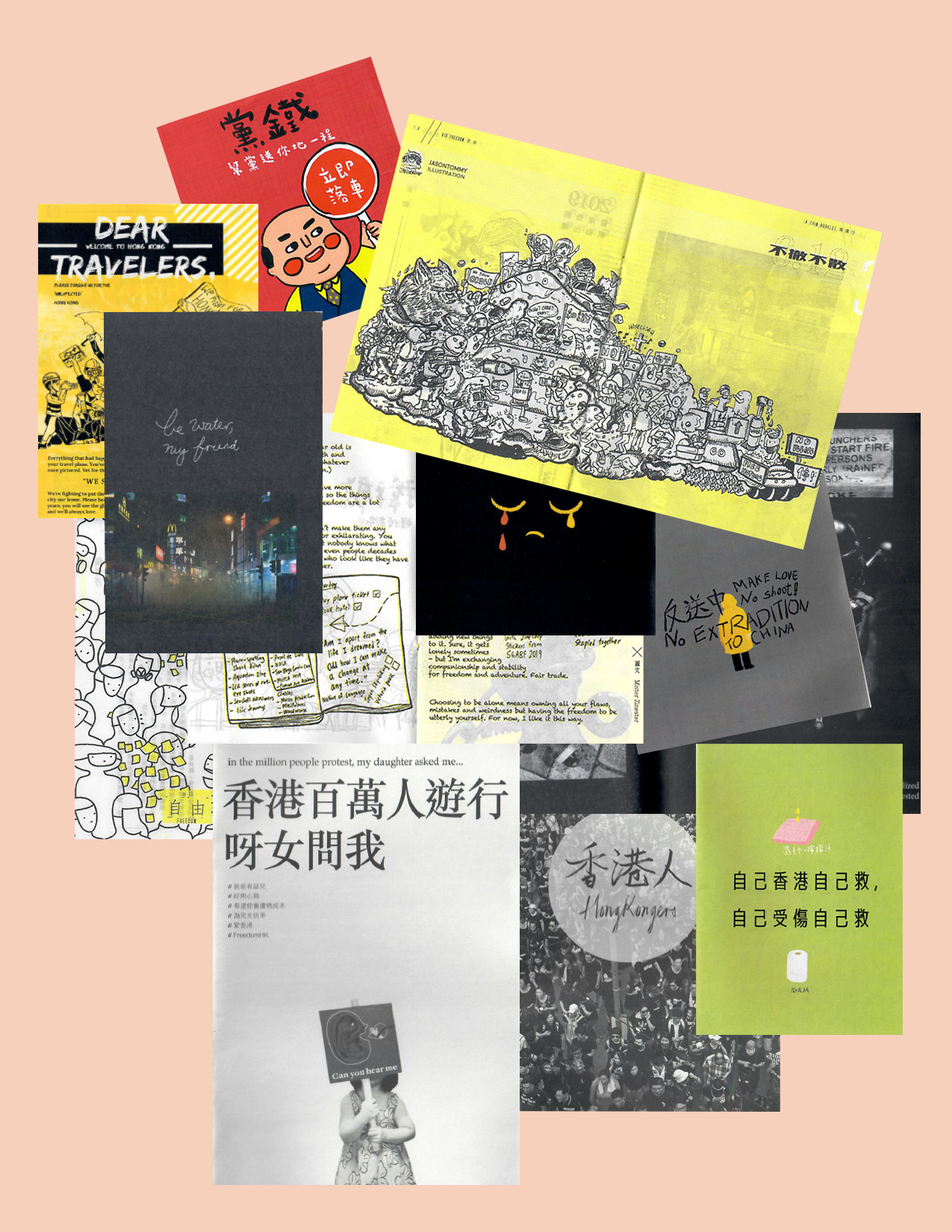

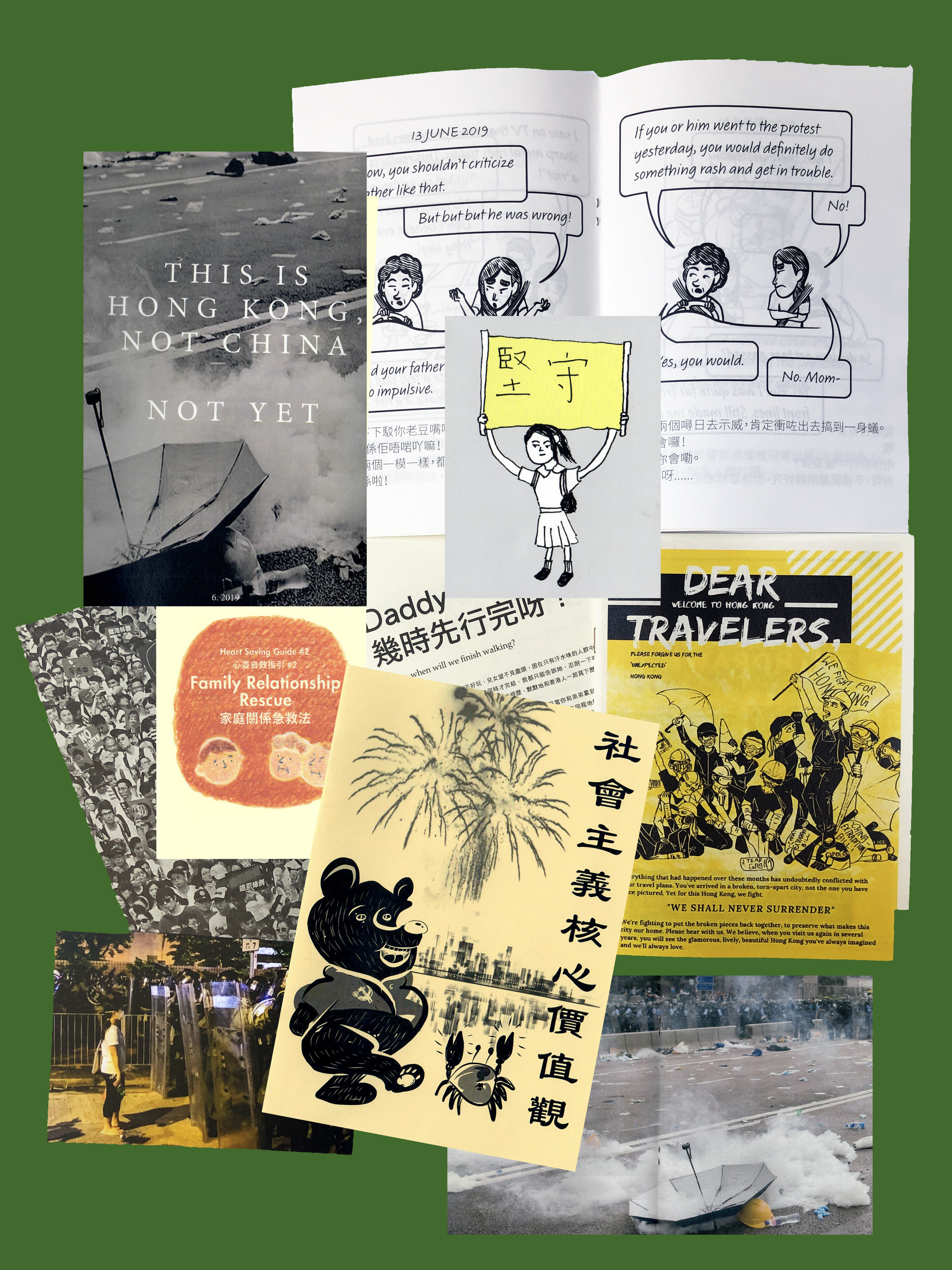

A year earlier, for Leadership Camp’s first session, my fellow campers and I packed into the basement of Asia Art Archive in America (AAA in A), the small but mighty New York outpost of the Hong Kong nonprofit dedicated to the documentation of recent art in Asia. After introductions, it became apparent that I’d be the sole non-Asian participant, the cohort’s minority. Artists Christopher K. Ho and Furen Dai, organizers of “Model Minority and Model Majorities,” then presented us with a series of challenging questions: Is it possible to leverage the “model” function of “model minority” to design new forms of leadership both inside and outside the art world, as opposed to merely affirming obsolete myths of assimilation? How and where do Asians fit into contemporary discourse about being a person of color? How does one build meaningful intercommunity and interethnic coalitions? This was the first day in a decidedly transformational experience—a collective attempt to “model” a form of leadership outside of wealthy white patriarchy—in a year marked by profound social and political struggle: seismic protests in Hong Kong, unending tensions between China and the United States, the ugly insurgence of racism against Asians in the United States, the ongoing Black Lives Matter protests, the toppling of Confederate monuments, renewed anti-racist movements, and a world-pausing pandemic. Dispensing with the notion that art is some great agent of liberation, the camp understood art as a fellow traveler with these conflicts, one that adapts to, brushes up against, informs, and is informed by them.

In discussions, campers could not agree on a single definition of “model minority,” but we did share a common understanding of the racist term’s origins: William Peterson’s January 1966 New York Times article “Success Story, Japanese-American Style,” which examines second- and third-generation Japanese-Americans’ adaptation to and performance in white American society. Within the framework of Leadership Camp, the idea of the model minority, the stereotype of a well-adjusted, upwardly mobile person of color long applied to Asians in the United States, raked against the proposition of “model majorities.” Sixty percent of the world’s population lives on the Asian continent, and China is poised to replace the United States as the world’s largest economic power as soon as 2030. As Ho recently said in an interview with November magazine, “We are not, or not only, minorities in the US and Britain so much as a global and cacophonous majority.” [footnote Christopher K. Ho, interviewed by Dawn Chan, November, no. 3 (2020) →.]

Before going further, let’s review some camp basics: each year, AAA in A issues an open call for applications to the program, each edition of which has been organized around an overarching theme. “Model Minority and Model Majorities” followed “Envisioning Institutions,” which explored how once-marginal locales might be epicenters of institutional change, and “Engendering Leadership,” which considered alternative forms of leadership that speak to and emerge from Asia. The current edition, “Other Racisms,” addresses not only racism against Asians but also “among and by Asians.” [footnote See →.] For the first meeting, Ho and Dai (an artist who assumed Wong Kit Yi’s role at AAA in A) assign readings related to the theme. The subsequent seminars are run by the campers, who choose texts that build on the discussion. Participants initiate parallel conversations outside of camp, and even convene for public programs at partner organizations, like the one held in November 2019 at the School of Visual Arts’s Curatorial Practice program.

Leadership Camp—subject to the affectionate jests of “campers”—evokes a sort of youth development program bolstered by a healthy dose of civic responsibility. And indeed, the camp was cofounded with a serious sense of purpose in 2016 by Ho and artist Wong Kit Yi, who then worked for AAA in A, after the two bonded over a mutual fondness for institutions during a studio visit. (A question for the reader: how does one love an institution, especially today?) Ho and Wong designed the camp as a place “where people could come together for the founding of an institution” and imagine new possibilities for art organizations. They pitched the idea to Jane DeBevoise, AAA in A’s founder, who understood the need for this type of program. “Institutions are conservative, they conserve themselves,” DeBevoise remarked. “It’s a different world” since the first call for proposals in 2016, and she expressed a real need to “respond to current situations and environments” by thinking about “institution-building and leadership from new perspectives, in this case through an Asian lens and Asian perspective.” Leadership Camp positions itself to un-conserve art’s institutions, to reimagine the idea of leadership from outside a traditional Western, Eurocentric framework. Why did Ho and Wong decide for this alternative pedagogical structure to be a “Leadership Camp,” as opposed to a workshop or more straightforward seminar? “I enjoy focus groups,” Wong said with a hearty laugh, before elaborating further: Leadership Camp could be “a safe and supportive environment outside of a school context to talk about art and representation.” In the second edition, “The term ‘leader’ was really thought through,” Ho explained, by “focus[ing] on specific people in the world as points of departure.” Curiously, they selected former First Lady of the Philippines Imelda Marcos, the Steel Butterfly herself, as an object of research and a foil to the idea of “leadership.” They did this for many reasons: she was female, a gay icon, a mythmaker, controversial to the point of well-justified outrage, and a dynasty starter with the uncanny ability to succeed in politics in the Philippines even after her exile. A key tenet of Leadership Camp is to ponder, Ho and Yi said, “What Asian social structures can inform models of contemporary leadership in the art world? And how can ‘we’ selectively deploy these?”

The satisfaction of Leadership Camp derives from the unique balance between informality and rigorous debate. (Artist Mark Dion’s idea of “productive hanging out” comes to mind.) Leadership Camp is “somewhere between a reading group and a social club,” recalled artist and writer Connie Kang, an alum of 2017’s “Envisioning Institutions.” Simon Wu, an independent curator and writer who participated in the same edition, agreed: “Leadership Camp is a pizza-fueled tri-monthly reading group, a discussion-led ‘hang-out,’ and a padded stage to test out divergent thinking on a one-to-one scale.” Mimi Wong, participant in “Engendering Leadership,” described the program as an “opportunity to think intellectually and theoretically about things in a way I hadn’t since undergrad,” like being “back in school.” For the artist Martha Tuttle, the 2019–20 Leadership Camp was “a space to form questions … around what being Asian American means in this moment, and what the possibilities of larger engagement are within our various [art] institutions [and] daily actions.” Yayoi Shionoiri, fellow “Model Minority and Model Majorities” participant and executive director of Nancy Rubins Studio and the Estate of Chris Burden, explained, “Ironically, it’s neither a leadership group nor a camp. To me, it feels like a book club, strategic policy meeting, activist kibbutz, and class section all rolled into one.”

I found Leadership Camp to be all of these things. I applied not only because of my art history background working with artists from Asia but also because of my position as director of the Yeh Art Gallery at St. John’s University in Queens, which is housed in the Sun Yat-sen Memorial Hall, a peculiar Cold War–era architectural monument to the political patriarch of the Republic of China. In the late 1960s, Dr. Paul K. T. Sih, a Chinese-born professor at St. John’s, commissioned a team of white American architects to design a modernist pagoda supported by donations from the Kuomintang’s Department of Information and the Republic of China’s Directorate General of Posts. The center opened its doors to students on September 6, 1973 as the university’s center for Asian studies. Faced with this loaded, sticky context in which to organize exhibitions, I hoped that by listening to the experiences of others I could further educate myself on how to position this platform, whatever power and privilege I might possess, toward more equitable future programming. Smaller institutions permit the flexibility necessary to evolve, to be ideally less resistant to museological change—a possibility inhibited by the power and wealth so deeply entrenched in the art world’s institutional behemoths that reforming the old guard seems a far-off reality.

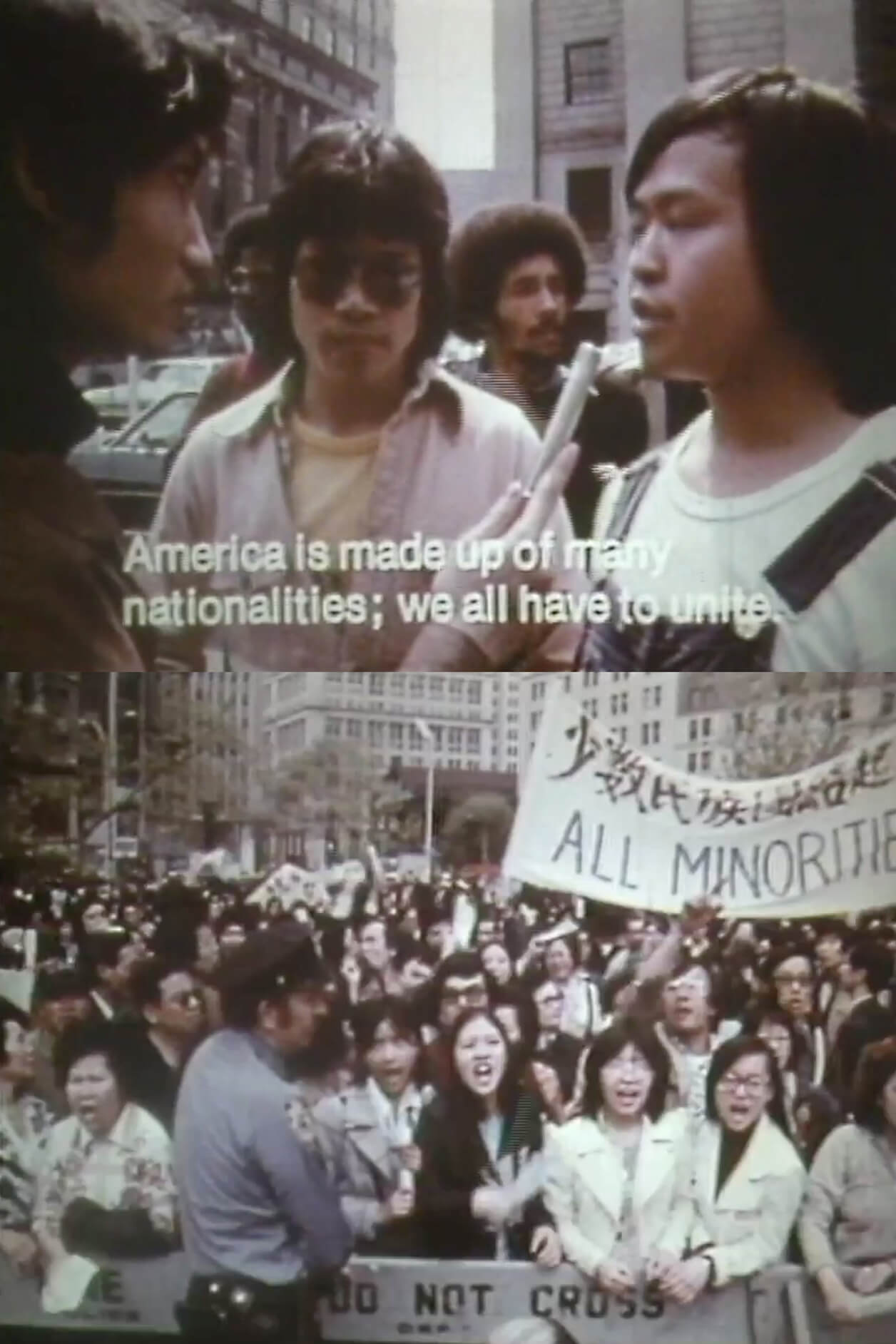

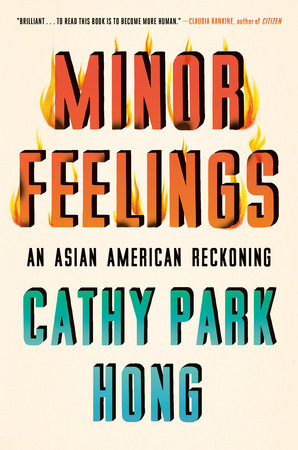

Ho and Dai initially gathered us back in June 2019 under the framework of discussing the “complex subject of Asians in America, and the even more complex subject position of Asian Americans, a term that encompasses diverse histories, languages, and ‘home’ country politics.” The goal of this specific camp was to develop new frameworks for Asian and Asian-American subjectivity in its multitudinous forms: at once a minority in America, but a global majority. Leading up to the final seminar, which was delayed several months by the Covid-19 pandemic, and eventually moved to Zoom, the group met to discuss a range of topics from the role of race in art institutions to the emergence of a mobile and global-educated Asian elite to an insensitive (or worse, racist) article in the New York Times about the movie Parasite and Confucianism. For the final virtual gathering, the discussion leaders, artists Martha Tuttle and Jesse Chun, pivoted the focus of the seminar, which was originally guided by the impossibility of discussing “our practices without also speaking about Covid-19, the emergence of racism and hate crimes in the face of the pandemic, our isolation.” In the wake of George Floyd’s murder, and the Black Lives Matter protests, Chun and Tuttle shared readings that examined the history of race relations between Asians in America and African Americans; these included the academic article “Organizing in Communities of Color: Addressing Interethnic Conflicts” by Margo Okazawa-Rey and Marshall Wong, and the essay “Nail Salon Brawls & Boycotts: Unpacking the Black-Asian Conflict in America” by Tiffany Diane Tso. [footnote Margo Okazawa-Rey and Marshall Wong, “Organizing in Communities of Color: Addressing Interethnic Conflicts,” Social Justice 24, no. 1 (Spring 1997) →. Tiffany Diane Tso, “Nail Salon Brawls & Boycotts: Unpacking The Black-Asian Conflict In America,” Refinery29, August 21, 2018 →.] Before we convened, Tuttle and Chun wrote to campers via email: “We believe that more than ever, we need to work on building Afro-Asian solidarity, as well as reflecting on our entangled histories in order to do better.” As we prepared for our final meeting together, Chun and Tuttle asked us to consider: “What does solidarity and rupture look like? What are effective models of allyship? And what are you asking of yourself and your practice during these times?”

In the ensuing conversation, campers debated the nature of white adjacency and assimilation, methods of reimagining institutional governance, and forms of direct action for racial equity. Camper Patrick Jaojoco shared his experience organizing, with curator Natalia Viera Salgada, the open letter “Arts Workers for Black Lives.” Signed by more than three thousand artists, curators, and creative professionals, the letter was addressed to New York City’s mayor, police commissioner, and district attorneys, as well as the state’s governor, and demanded the defunding of police and investment in BIPOC communities. Jaojoco felt like there has been “not a lot of concrete actions” from the art world, especially from controversy-adverse institutions, and so the two “decided to write a letter.” Jaojoco acknowledged the need for progress “beyond just a letter or a single action” and that “some of this change will be relatively slow,” but “it’s urgently needed to happen now.” So, Jaojoco explained, signatories to the letter “formed core working groups” to share resources and information, to organize, and to realize a world without police. Since then, AW4BL operates with ten to fifteen participants, and formally testified at an NYC public hearing on Black Lives Matter, systemic racism, and anti-racism in the arts, as they continue to plan their activism for 2021. Overall, the organic, participant-led nature of Leadership Camp allowed the seminar to progress from a discussion of subject positions and identity to seeding actions to address urgent needs.

Asset mapping showed what white adjacency (or in my case, white privilege) looks like in financial terms. In light of the session’s readings about this history of conflict and community organizing across Asian and Black communities in America, the activity seemed intent on underscoring the relative privilege of Asians in America compared to Black, brown, and Indigenous people. There was a definite discomfort in seeing this new wealth of data. Does it come as a surprise that Leadership Campers are not poor? Not everyone was a one-percenter, either, but still, our backgrounds were primarily middle and upper-middle class. Would power be redistributed through art’s institutions if we were transparent about our net worth? Could it reveal not just our salaries, but the true subject positions from which we speak? We might learn more about each other’s motivations, not to mention material needs, and the hierarchies that govern art’s institutions might be set in stark relief. (What would an asset map of MoMA tell us?) It should be noted that some participants felt unresolved, if not uncomfortable, at the end of the camp. Jaojoco reflected: “Leadership Camp has been a place for not necessarily building ‘leadership,’ but to share thoughts, experiences, and readings about challenging the model minority stereotype of Asians in America. I guess that this is a method for building leadership, empowering the Asians in the group through collective wisdom-building and sharing strategies for empowerment.” However, he cited colorism as detracting from his experience, which “was also somewhat uncomfortable” because the group was “predominately East Asian. [This] was increasingly uncomfortable to me, and only worked to further bring up the question of what Leadership Camp is, exactly, and what the framework of ‘leadership’ with which we were working was.”

What’s happened after camp? Since the conclusion of “Model Minorities and Model Majorities,” campers have continued working and dialoguing together. For example, Celine Wong Katzman recently produced with Diane Zhou Consider the Scallion, a risograph publication that explores the cultural importance of the scallion and features contributions by fellow campers Luke Luokun Cheng, Matthew Shen Goodman, and Mo Kong (among others). Camper Daisy Nam and Ho are coediting an anthology to be published by Paper Monument titled Best! Letters from Asian Americans, which features reflections from approximately seventy authors, many of whom are former campers. Moreover, Jaojoco’s identification of our cohort’s emphasis on East Asian experience directly impacted the subsequent edition of Leadership Camp, “Other Racisms.” Ho shared with me guiding questions that encouraged the next camp’s participants to engage with hierarchies between South, East, and Southeast Asians. “What if the ‘other’ in ‘Other Racisms’ is replaced with ‘our?’ What are our racisms?” Ho and Dai wrote. I asked Ho over the phone, with so much reckoning that needs to happen in the United States, “Why consider looking at racism elsewhere in the world?” For Ho, to focus exclusively on the United States would be an exercise in itself that privileges Western views of the world. “If we are to talk about racism,” Ho shared, “we must talk about the racism of the world’s majority.”

At a time of widespread institutional disillusionment over the debt burdens and returns on investment of many MFA programs and the coziness of major museums and titans of extractive industries, there’s a possibility to develop meaningful alternatives to the mainstream art world. Leadership Camp convened a free, genuine critical forum, an educational setting that offered all the perks of grad school without its pitfalls. Thought-provoking intellectual engagement, a sense of community, and an opportunity to network, frankly, with peers were all to be found. Leadership Camp is doubly alternative in this sense: it also offers a pedagogical model that takes its cues and structures—refreshingly and necessarily—from outside the West. It’s a seminar, yes, but, for example: Asian figureheads are the objects that guide the pedagogy: what’s there to learn from studying the Iron Butterfly? As in “Other Racisms,” what happens when “caste mapping” replaces the Western-oriented idea of asset mapping to emphasize the nuances of social stratification that money alone does not attend?

In November 2019, I saw David Henry Hwang’s Soft Power with Ho at The Public Theater, an experience outside of Leadership Camp but one vitally relevant to its discussions. Part autobiographical, and certifiably meta-theatrical, Soft Power begins by following a playwright, also named David Henry Hwang (Francis Jue), a few days after the 2016 presidential election. He’s assaulted by a knife-wielding assailant, and proceeds to hallucinate a musical in which Xue Xing (Conrad Ricamora), a Shanghainese producer, lands at LaGuardia Airport and enters a courtship with Hillary Rodham Clinton (Alyse Alan Louis). Hwang’s musical offers a vision of multicultural America but reminds the audience from its first song that political power presently remains entrenched with, or at least adjacent to, whiteness. Soft Power inverts the orientalist story arc of The King and I, and, with humor and ironic glitz, weaves the intricacies of cultural diplomacy, China’s twenty-first century quest for soft power, and the shortcomings of American democracy into an impactful musical on cultural identity and racism. When Xue and Clinton fall for one another, they duet “It Just Takes Time,” a libretto crafted around Clinton’s fumbling of Mandarin’s tones and Xue Xing’s patient coaching. “I must say—I never asked my lips to go that way,” Louis sings. The ridiculousness of the exchange illustrated the sometimes cringing discomfort and shortcomings of liberal allyship, no matter how well-intentioned. “It just takes time,” Ricamora croons. That time is past due.

Christopher K. Ho, interviewed by Dawn Chan, November, no. 3 (2020) →.

See →.

Margo Okazawa-Rey and Marshall Wong, “Organizing in Communities of Color: Addressing Interethnic Conflicts,” Social Justice 24, no. 1 (Spring 1997) →. Tiffany Diane Tso, “Nail Salon Brawls & Boycotts: Unpacking The Black-Asian Conflict In America,” Refinery29, August 21, 2018 →.