Field Notes is a new series of reviews from the next generation of art writers. Featuring texts on the 59th Venice Biennale and Documenta 15 contributed by students and recent graduates, Field Notes makes original connections between the work and the world and takes a closer look at what other observers might have missed.

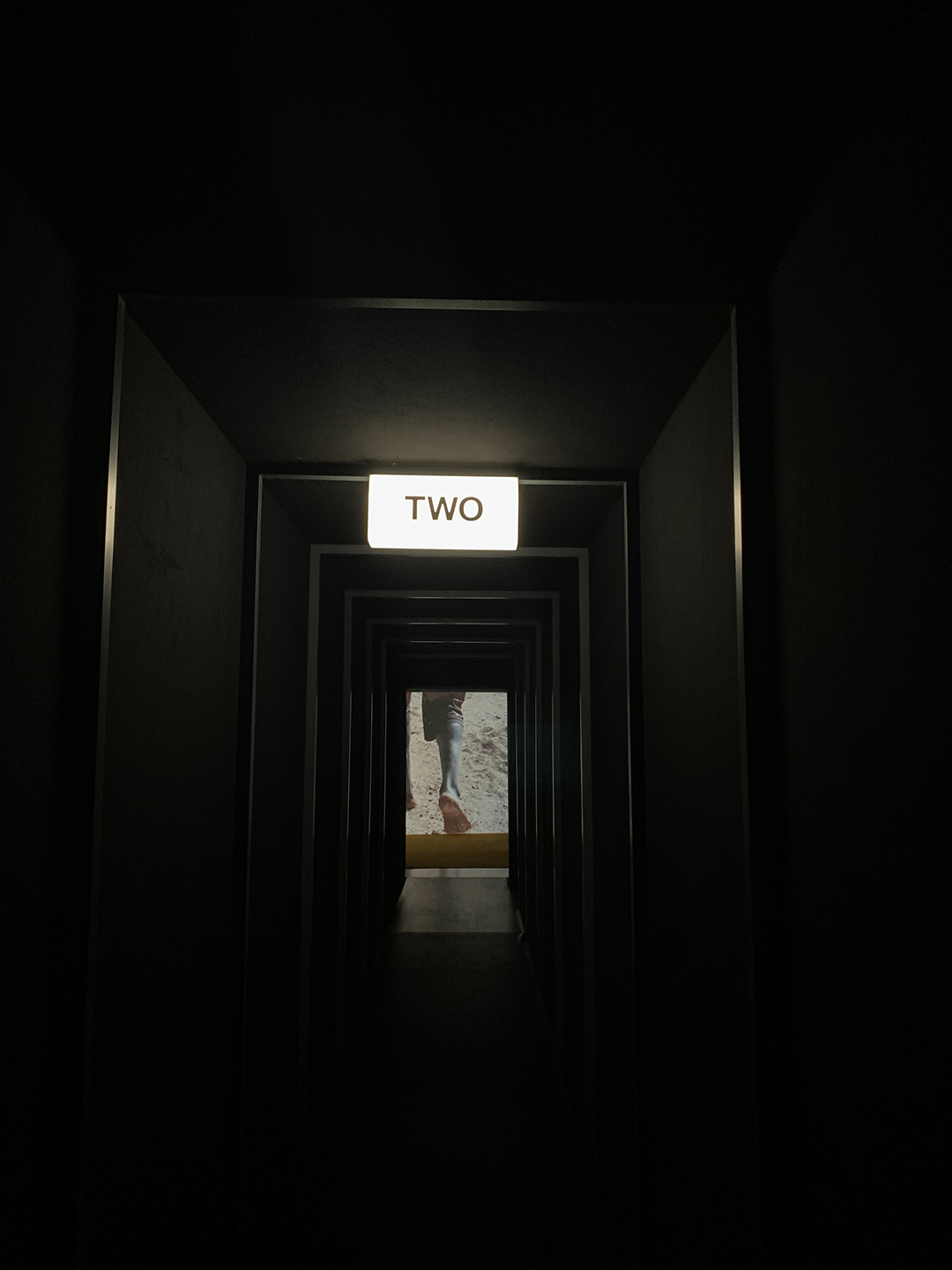

Set in a sixteenth-century emergency shelter turned church turned cultural center, “Penumbra” presents eight newly commissioned video installations by Karimah Ashadu, Jonathas de Andrade, Aziz Hazara, He Xiangyu, Masbedo, James Richards, Emilija Škarnulytė, and Ana Vaz and is organized by Fondazione In Between Art Film on the occasion of the 59th Venice Biennale. The exhibition’s title provides a loose framework. Referring to the zone of partial illumination between shadow and light, it generates associations with both the light reflected from a film screen in a dark theater and the shadows cast by celestial bodies during an eclipse. The presentation accentuates film’s potential for perceptual play, drawing on the worlds contained in them, the physical viewing spaces, and the space between. Repurposed as an exhibition space, the Complesso dell’Ospedaletto is full of reminders of its past functions. Installed among in the building’s eerie offices and lavish Baroque altars, the films not only produce a striking contrast between old and new but also create a sense of continual shapeshifting. In an opposite pull, each installation is announced by a numbered lightbox reminiscent of those at a cinema designating individual theaters, bracketing each work with a signal of more traditional film presentation. Together, these two effects alternatingly establish and break down the expected boundaries of the screen.

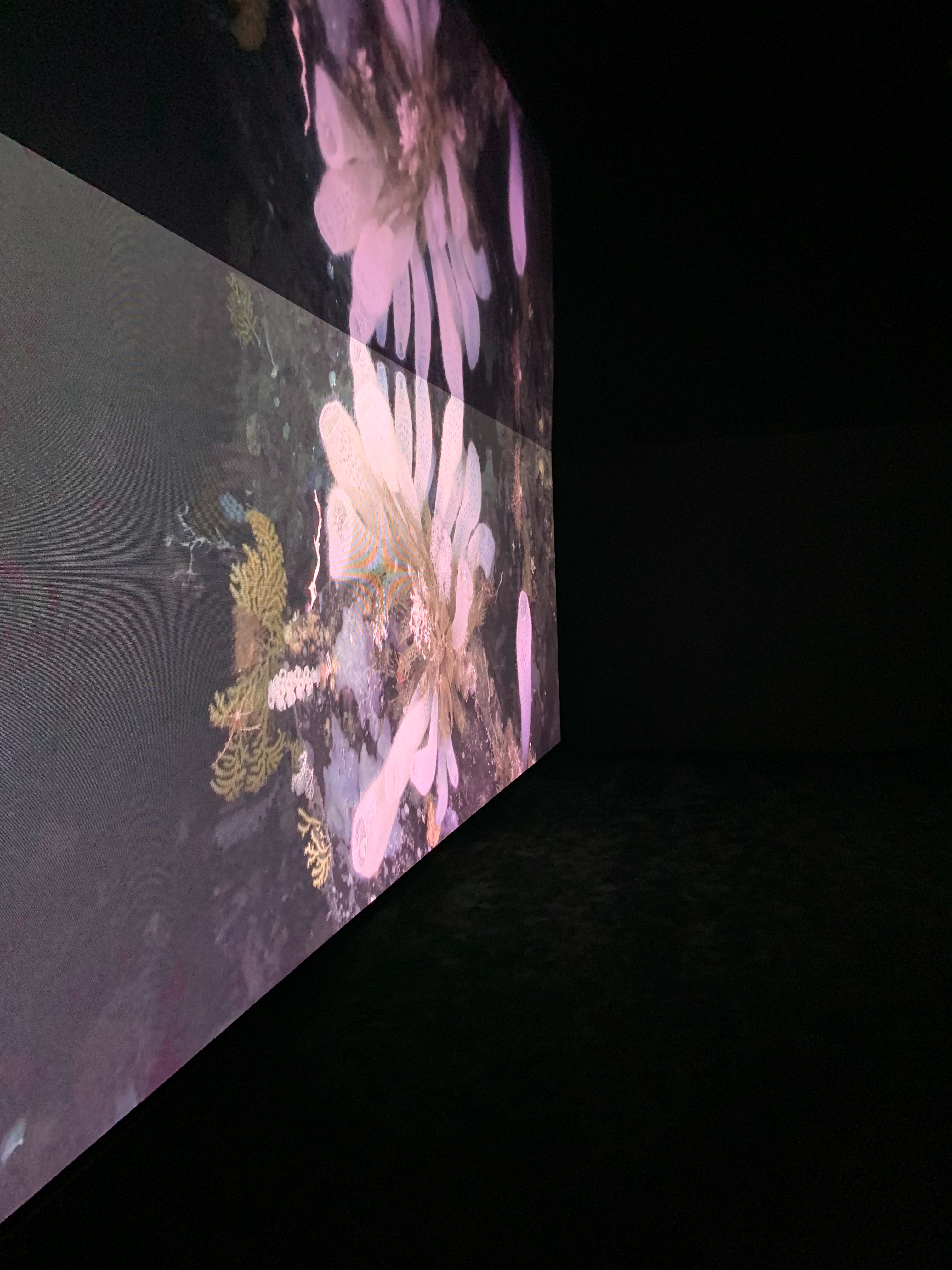

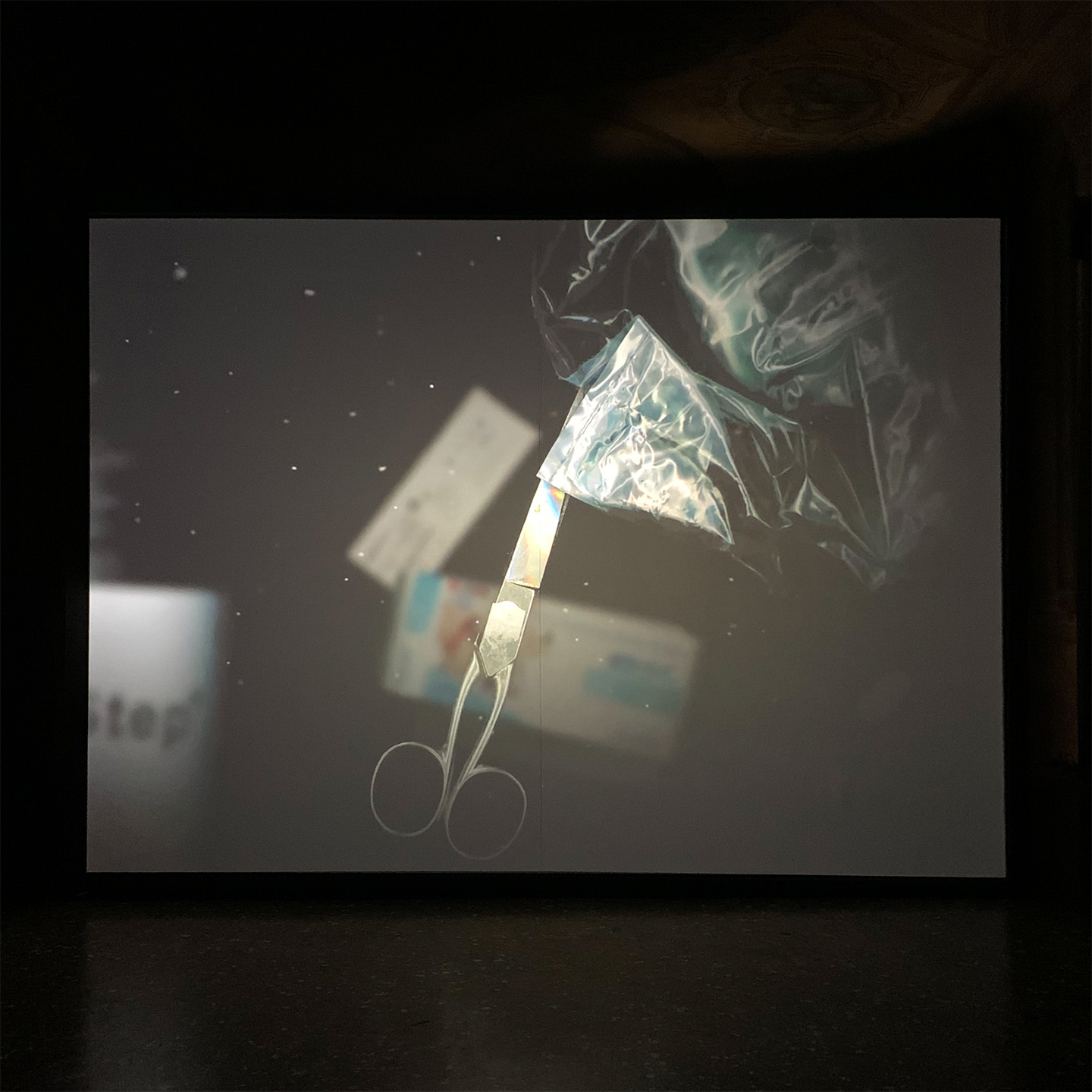

Two films explore surface in content and form. In James Richards’s Qualities of Life (Living in the Radiant Cold) (2022), the artist takes an endoscopic approach to his own bodily interiors. The film incorporates footage from an MRI scan into a body of views that poetically interpret the theme and iconography of medical care. Pills and toenail clippers, among other objects swept up from the artist’s apartment and studio, float in an ambient black space to an eerie soundtrack with the lyrics “my, my, my apocalypse.” The installation design increases the sensation of diving under the surface: upon entering the space, a massive black wall blocks access to the screen, making the visitor’s first experience of the work aural rather than visual. In this way, an intense, moody interiority foregrounds the appearance of sterile objects and medical imagery. Aphotic Zone (2022), by Emilijia Škarnulytė, dives into the pitch black depths of the Gulf of Mexico. In this blackness—the watery region of the title—marine scientists from Temple University are endeavoring to find a super coral species that can survive human-caused ocean warming and acidification. Advanced technologies like robotic arms penetrate the oceanic layer. The smooth and shiny black ceiling of the long gallery hosting the film reflects images on the screen, producing a doubling illusion or evoking the very depths that the different filmed machines descend through. The film’s audio palpably rumbling in the gallery amplifies the sense of being surrounded.

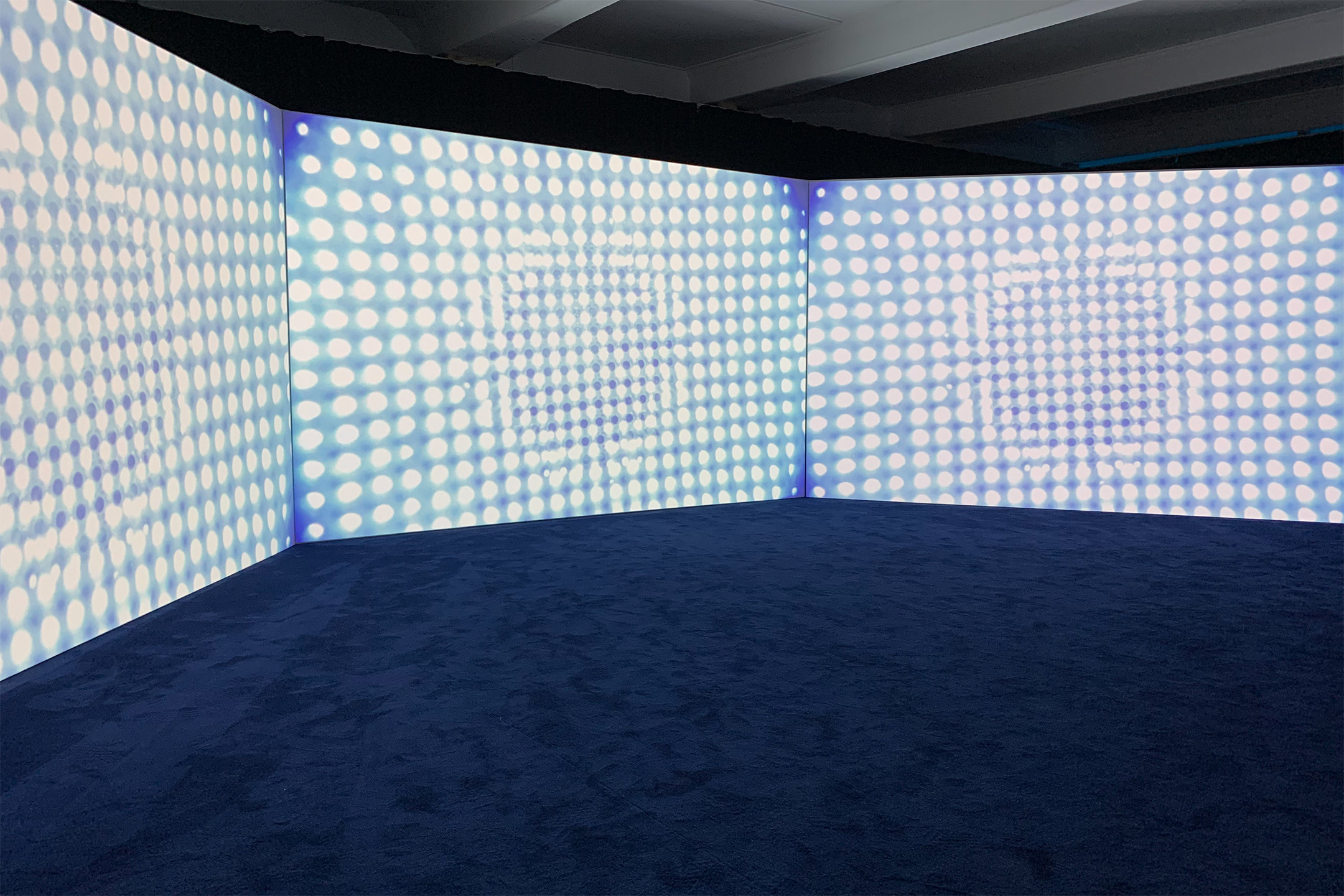

Beneath the surface, moments of intense closeness seem possible. Shot on expired 16mm film, Ana Vaz’s É Noite na América [Night in America] (2021) follows the Brasília Zoo’s veterinary team and environmental police on a series of animal-rescue missions. Due to the ongoing effects of urbanization and pollution of the Brazilian Cerrado, endangered species have been pushed into urban settlements, where they encounter human inhabitants. Vaz’s installation evokes this unnatural proximity. Presented across three connected channels angled inward, the floor-to-ceiling screens enclose the viewer’s field of vision and merge with it. An otter’s leg flickers in the corner of the far left screen before its full body comes into focus, evoking the sensation of seeing something out of the corner of the eye, and three competing sets of close-up shots render the erratic movements of the barking, screeching, thrashing creature.

In Jonathas De Andrade’s Olho da Rua [Eye of the Street] (2022), the screen is a vehicle for playing with proximity, distance, and the distribution of knowledge. For the film, de Andrade worked with a homeless community in downtown Recife, where he also lives. His methods directly invoke that of Brazilian theater director Augusto Boal’s Theater of the Oppressed, which aims to incite political and social change by creating conditions in which theater audiences interject performances to transform the roles their members play in society. De Andrade’s work is organized into eight “acts.” In Act 1, prismático [prismatic], subjects take turns admiring themselves in a mirror leaned against a tree trunk, performing acts of grooming, inspecting, styling, and ogling. With the appearance of each subject, the camera progressively zooms in until the bounds of the mirror are no longer visible, collapsing with the screen or eye of the viewer; though de Andrade never appears, the film registers his presence through the camera. However, as participants in de Andrade’s film, the subjects play with awareness of the camera and the audience, contesting the illusion of unfettered access to their daily lives and intimate moments. In Act 7, boca livre [out loud], the subjects form a circle, and individuals or groups jump into the center and voice demands for housing, jobs, and an end to anti-trans violence. Surrounded by members of their community, the speakers face the camera and direct these calls to both the right-wing Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro and the viewers of the film. One speaker states, “If you are watching this video, remember that I’m a person. You don’t have to look with bad eyes. Embrace, welcome, don’t punish.” In the work’s final act, olho no olho [eye to eye], the camera slowly pans across the subjects arranged in a line. Some blow kisses, some pose, and some lean in and stare back at the camera, withholding any glimpse into their interiority. While Theater of the Oppressed hinges on interaction between audience and performer, moments of self-fashioning enacted by the Olho de Rua’s subjects push against de Andrade’s authority as facilitator.

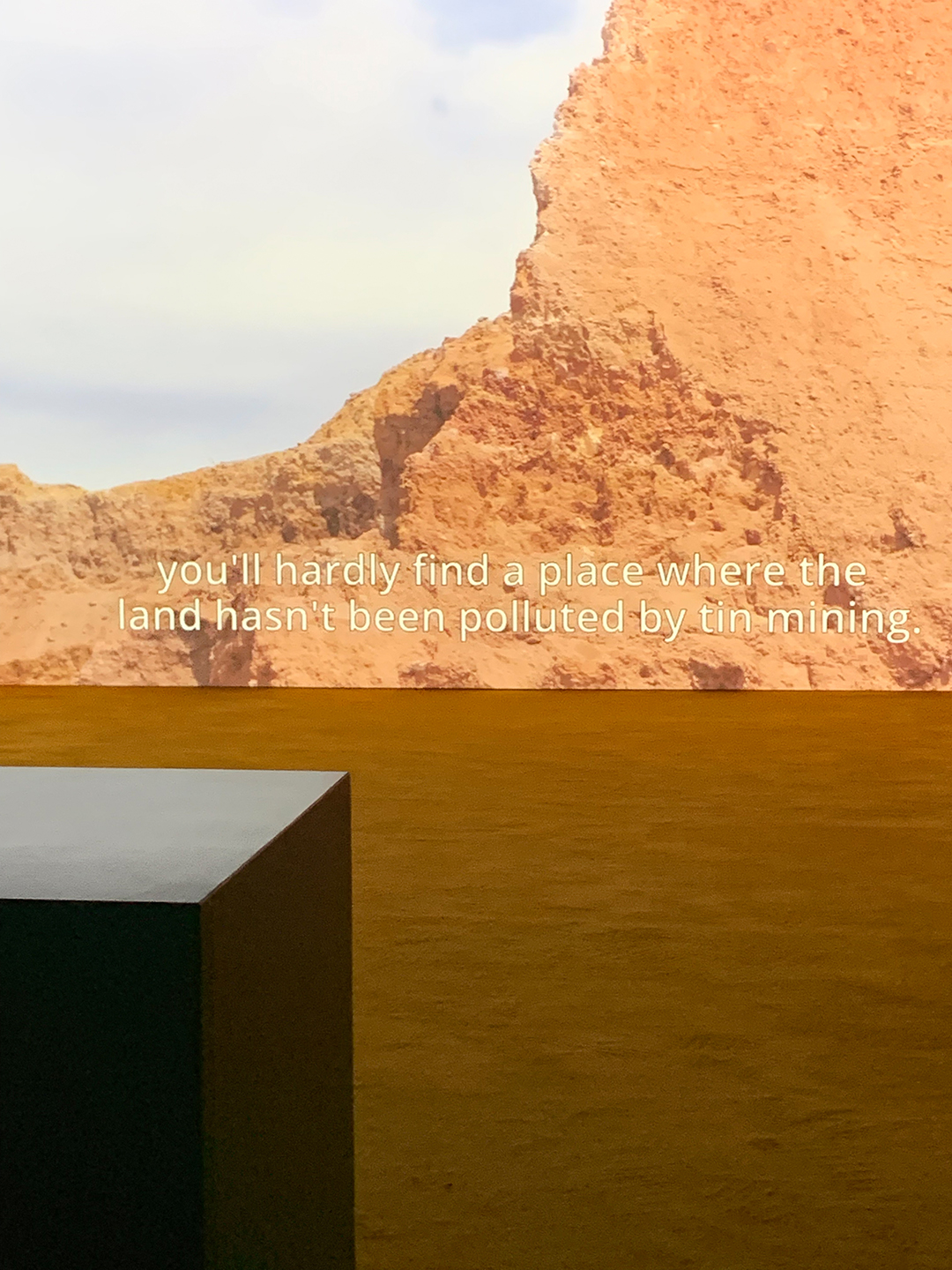

Film works extend onto the Complesso dell’Ospedaletto’s carpet, ceiling, and walls, rendering the screen the surface of a voluminous space rather than a 2D projection plane. Plateau (2021), by Karimah Ashadu, depicts a group of undocumented tin miners in Nigeria’s Jos Plateau region arduously digging and sifting dirt and descending into narrow mine shafts. In the aftermath of the British colonial exploitation, ecological havoc, and unsafe working conditions, tin mining makes for an especially difficult way of life. Subjects reflect on these challenges, but with the industry so central to their livelihood, and so much work to do, an alternative seems beyond the bounds of the screen. Instead, the work focuses on their labor and techniques—its intense physicality and duration—and the charged visual landscape. The installation is accessed through a dark, narrow corridor like a mineshaft, and the film is presented across two channels on perpendicular walls connected by ocher wall-to-wall carpeting. Between the two screens, long panning shots lag behind each other and form a surround, enclosing the viewer in a rust-colored cavity evocative of the depressed gullies in Ashadu’s film.

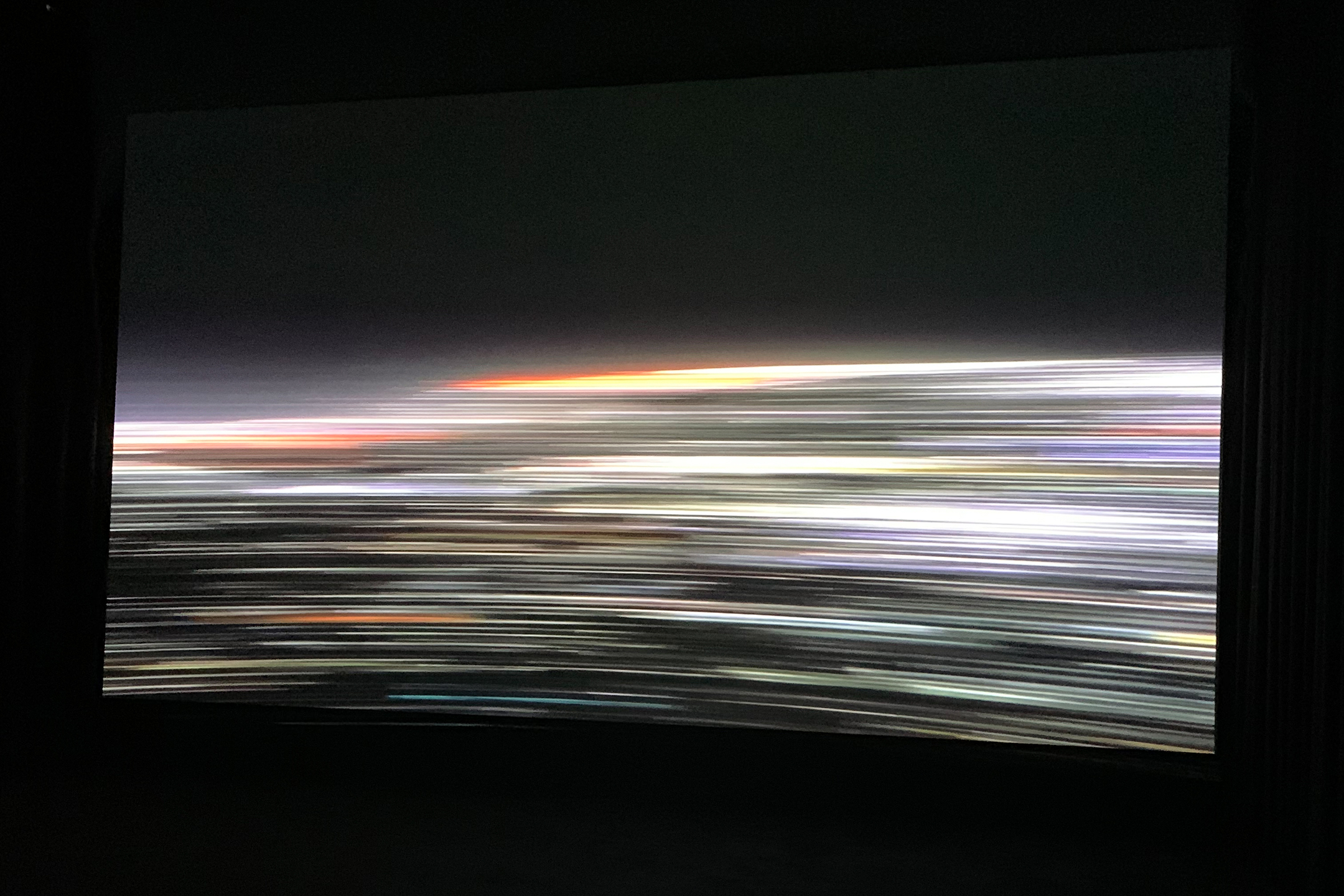

Aziz Hazara’s Takbir (2022) explores nocturnal darkness as a space activating two political flashpoints in Kabul’s history: the 1980s, when residents protested the Soviet occupation, and the end of the United States-led NATO invasion in 2021, when residents once again shouted the Takbir in defiance. In the work, quiet drone-like shots of a glimmering Kabul transform into swirling, elliptical lines of light piercing through the darkness when the Takbir rings out and the camera begins spinning rapidly. The Takbir, “Allahu Akbar,” has a multitude of religious and cultural uses, from formal prayer to expressions of joy or distress to calls for protest. (The exhibition text emphasizes how the phrase was appropriated by both the US War on Terror and the Taliban for discrete political agendas). Here, however, the Takbir propels a whirlwind of sonic resistance that devolves into visual abstraction. The work is set in total, enveloping darkness, with the carpeting and ceiling blending into the pitch black night on screen, collapsing the liminal space of night with the transitory space of the enclosed viewing room.