With inclusion at the center of Documenta 15—of artists from diverse backgrounds and cultures, of the public in the exhibition—it perhaps should not surprise that this edition of the quinquennial has also involved children in a way unprecedented in exhibitions of contemporary art. ruangrupa emphasizes children’s activities in its curatorial strategy, recalling Dutch director Willem Sandberg’s 1962 exhibition “Dylaby,” which he collaboratively organized with artist Jean Tinguely at the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam and in which children were active participants while they were present in every possible way. [footnote Paula Burleigh, “Ludic Labyrinths: Strategies of Disruption,” Stedelijk Studies 7 (Fall 2018): 6–8.] Separated by six decades, “Dylaby” and Documenta 15 can both be understood as labyrinths that encourage visitors to meander and explore and to playfully engage with works of art, exemplifying a kind of presentation that art historian Janna Schoenburger has called “ludic exhibitions.” [footnote Janna Schoenburger, “Ludic Exhibitions at the Stedelijk Museum: Die Welt als Labyrinth, Bewogen Beweging, and Dylaby,” Stedelijk Studies 7 (Fall 2018): 2. Schoenberger states that those ludic exhibitions had an oblique political stance. This is where “Dylaby” and Documenta 15 diverge. This edition of Documenta is defiantly political and critical of the very foundations of Western museums and institutions. And most importantly perhaps, the exhibition demonstrates the possibility of presenting art that is embedded in life rather that in the market or museum, both of which correspond with Western imperial structures.] In this regard, art historian Paula Burleigh has stated that the presence of children symbolizes the ludic nature of such labyrinthine exhibitions. [footnote Burleigh, “Ludic Labyrinths,” 6.] For Documenta 15, children, artists’ collaborations with them, and representations of their actions animate the exhibition and its attending discourses, expressing ruangrupa’s desire to reframe visitors as active participants in rather than passive observers of contemporary art.

Upon entering the Fridericianum, Documenta’s historical headquarters, visitors are welcomed by RURUKIDS, an initiative that is not exclusively concerned with art or artists but instead is a dedicated community space for children of all ages. In this space, where one would expect to find artworks, Graziela Kunsch—“an artist, educator, and mother”—has opened Public Daycare, a functional parental daycare based on studies on infant education by the twentieth-century Hungarian pediatrician Emmi Pikler. [footnote See →.] Pikler argued that parents should not intervene in the motor development of infants as they will intuitively figure out how to act. In this way, according to Pikler, infants do not only learn how to move in their environment but they learn how to learn. [footnote See Emmi Piker, “The Development of Movement-Stages”, The Pikler Collection, →. Importantly, RURUKIDS is not detached from the exhibition, unlike dedicated spaces for children in most Western art museums today, but occupiers a central place in ruangrupa’s reimagining of the Fridericianum as Fridskul, where people can gather and exchange ideas and experiences. Although RURUKIDS is dedicated primarily to activities for children, its ludic nature demonstrates what ruangrupa has hoped to create for visitors of all ages with Documenta 15: a belief in the possibility of producing art that is embedded in life rather than museums. [footnote ruangrupa states that art is rooted in life several times in their introduction in Documenta 15 Handbook ruangrupa, “Introduction,” Documenta 15 Handbook (Ostfilderm, Germany: Hatje Cantz Verlag, 2022). In this regard, it is also quite telling that chairs of Fridskul Common Library, which were produced by lumbung member collective El Warcha, echo Pikler’s triangle which she developed to teach children how to climb. This is yet another indication of RURUKIDS embeddedness in the exhibition discourse. Like Pikler’s infant, visitors, too, learn how to move through thirty-two exhibition venues scattered around Kassel.] ruangrupa’s ambition to make this exhibition an open, ludic space is made evident, for example, by the fact that they have granted Kassel skateboarders free access to Documenta Halle, where Baan Noorg Collaborative Art and Culture invites them to participate in the skate park installation The Ritual of Things.

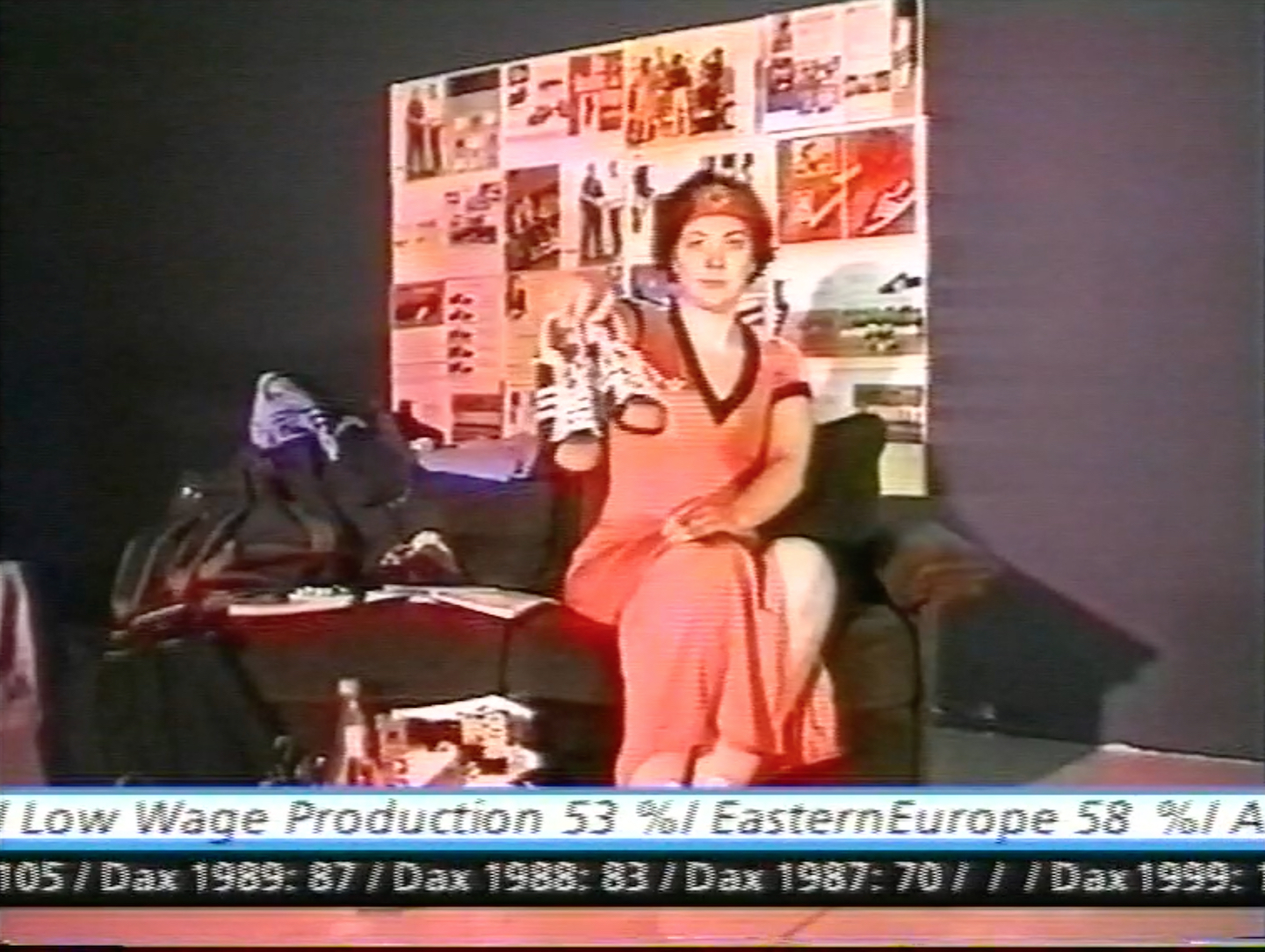

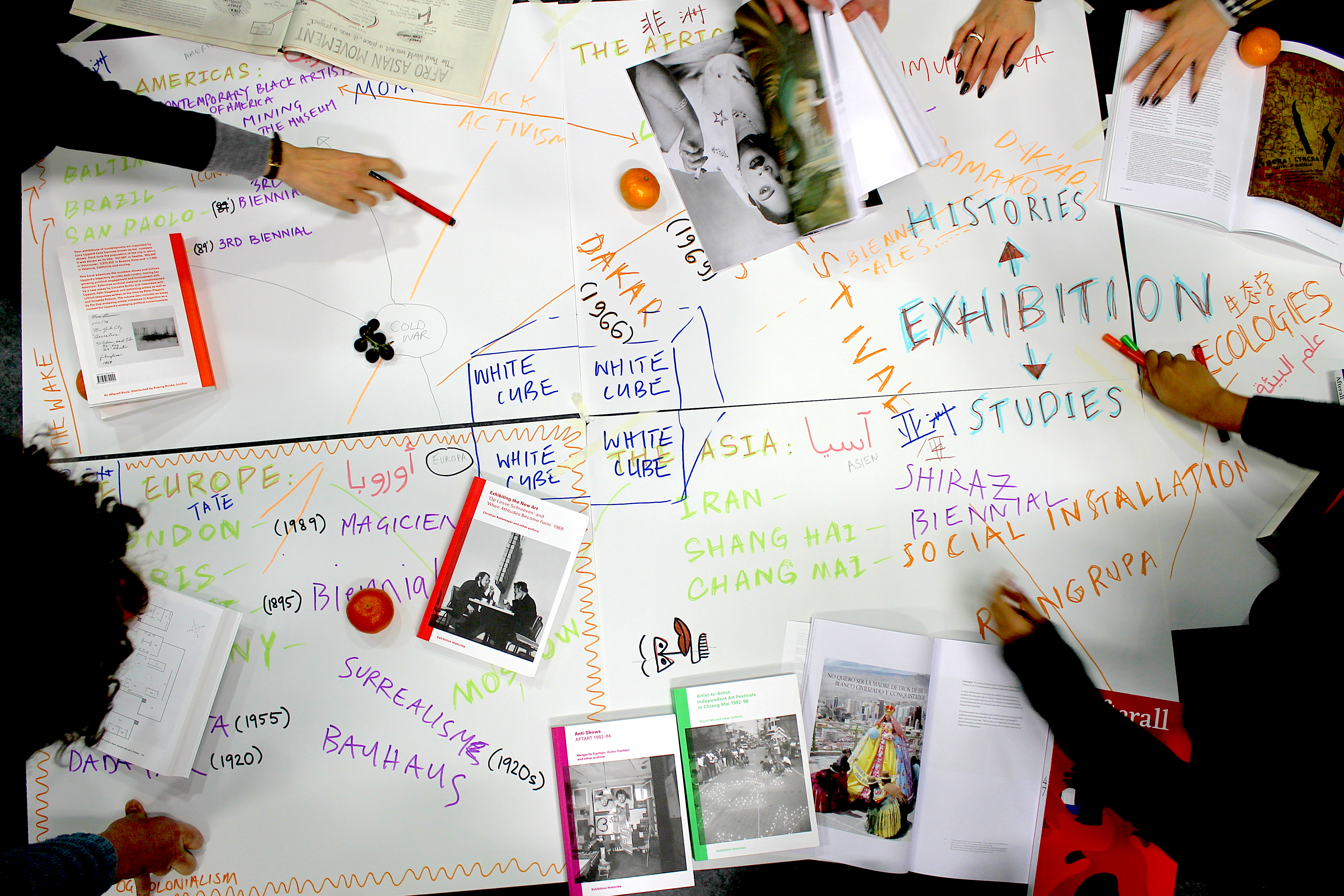

In addition to Kunsch’s Public Daycare, RURUKIDS has hosted several workshops for children by Documenta 15 artists, such as “How do I see art?” and “Images and Stories in Motion.” These public learning engagements have encouraged participants of all ages to think about the concept of art and how the artists’ projects in Documenta embody their understandings. Furthering children’s collaboration with the exhibition, Documenta 15 recently premiered a trailer for a sitcom produced entirely by a group of Kassel high school students that follows the comic interactions of three teenagers with ruangrupa’s organizing principle of lumbung. [footnote See →. The sitcom is yet another echo of “Dylaby” in Documenta 15. Paula Burleigh has underlined that one of the clearest indicators of children’s involvement with “Dylaby” was a documentary film, narrated and led by a child, that demonstrates children’s willingness to participate in the exhibition and adults’ puzzlement with it. See Burleigh, “Ludic Labrythins,” 8. A similar strategy could be found in Roger M. Buergel and Ruth Noack’s documenta 12 (2007). In that exhibition, popular guided tours were led by children. See Anthony Spira, “Infancy, History and Rehabilition at documenta 12,” Journal of Visual Culture 7, no. 2 (August 2008): 228.] Moreover, ruangrupa has published a family guide in the form of a comic book to accompany the exhibition. This gesture underlines how ruangrupa has been attuned to the dynamics of Kassel, a city that is home to the cartoon and comics museum Caricatura. But perhaps ruangrupa’s strongest statement about the inclusion of children was Indonesian artist Agus Nur Amal PMTOH’s performance at the opening press conference, which emerged from his collaboration with Kassel schoolchildren on a project about the past, present, and future of the natural environment. While addressing climate change, Agus’s performance also referred to the importance of listening to children’s voices as they too are citizens of this world.

Agus’s work continues in the Grimmwelt Museum, an institution dedicated to the works of the children’s fable writers the Brothers Grimm. There, the artist’s installation Tritangtu fills a large exhibition space with a wide range of everyday objects and toys and displays videos that exemplify how artists' engage with children from various schools through a musical storytelling practice called hikayat. In a space where the Brothers Grimm’s legacy is celebrated, Agus’s work, created collaboratively with children, lets them share their visions and chart their own paths towards maturity, profoundly subverting the conventional management of knowledge in which children and adults are respectively cast in fixed roles as receivers and distributors. While fable writers such as the Brothers Grimm sought to impose Christian and Western bourgeois values on children through their stories, Agus’s collaboration gave them space to act and make sense of the world on their own terms. [footnote See Jack Zipes, Fairy Tales and Art of Subversion (New York: Routledge, 2006), 59–80. Agus’s work also recalls Francis Alÿs’s work The Nature of the Game for the Belgian Pavilion at the 59th Venice Biennale. In a recent interview about this work, Alÿs stated: “Adults tend to process traumatic experiences through speech. Children will do it through a play, and I thought this game was a beautiful example of how. To think that children are disconnected is wrong, they are actually very affected and connected and trying to make sense of what’s happening around them.” See →.]

Baan Noorg Collaborative Arts and Culture, The Rituals of Things, 2022. Skater on the half-pipe, Fridericianum, Kassel, June 13, 2022. Photo: Nicolas Wefers.

It is difficult to predict the near-future effects of Documenta 15, or Lumbung 1, as ruangrupa calls it. But this edition will certainly be remembered for how children were engaged as collaborators, perhaps creating a new generation of artists to participate in Lumbungs yet to come. ruangrupa advises “Make friends, not art!,” and RURUKIDS’s foregrounding of experiment and play and Documenta 15’s various other projects with children encourage precisely that. [footnote ruangrupa, “Introduction,” Documenta 15 Handbook (Ostfilderm, Germany: Hatje Cantz Verlag, 2022), 9.] Art, for the collective, manifests as a way of sharing life with friends—with all its attendant horrors and joys—a concept that inherently transforms the viewer from a passive subject to an active participant. In this regard, Documenta 15 recalls philosophers Alva Nöe and J. Kevin O’ Regan’s idea that “visual experience is not something that happens in individuals. It is something that they do.” [footnote Alva Nöe and J. Kevin O’Regan, “On the Brain-Basis of Visual Consciousness” in Vision and Mind: Selected Readings in the Philosophy of Perception, eds. Alva Nöe and Evan Thompson (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2002), 567.] Documenta 15 invites adults to act and inhabit the exhibition spaces and experience it along with children, as neither RURUKIDS nor the exhibition itself are intended for one group or the other. Thus, children’s role in this exhibition is twofold. First, it symbolizes the ludic nature of the exhibition, as children are more willing to be active participants. Second, it underlines that children’s actions and ways of seeing, however enigmatic or juvenile they may be, are no less important than those of adults. Perhaps by adopting their orientation with the world, including making friends and playing in every possible way, adults might transform their experience of art and life. This stance of runagrupa makes this edition of Documenta a skul without walls for both adults and children where we walk together, make friends, play, and learn when we want, as we want. [footnote Of course, Documenta 15 is not the first exhibition who led visitors to walk in the exhibition city. The list of such exhibitions would be endless, especially since the 1990s. What makes this edition of Documenta important is its insistence on children’s inclusion into meanderings that the exhibition charts. In this regard, it reminds the notion of “streetwork,” which was promoted by anarchists Colin Ward and Tony Fryson during 1970s and 1980s. Catherine Burke has stated that: “The notion of streetwork transformed environmental education into a radical urban form which envisaged children and young people as actively engaged resourceful responders to their immediate environment. An inspiration for Ward and Fyson was the fiction of Paul Goodman who developed the idea of the “exploding school” which realised the city as an educator.” See Catherine Burke, “Feet, footwork, footwear, and “being alive” in the modern school”, Paedagogica Historica 54 nos. 1/2 (2018): 41.]

Paula Burleigh, “Ludic Labyrinths: Strategies of Disruption,” Stedelijk Studies 7 (Fall 2018): 6–8.

Janna Schoenburger, “Ludic Exhibitions at the Stedelijk Museum: Die Welt als Labyrinth, Bewogen Beweging, and Dylaby,” Stedelijk Studies 7 (Fall 2018): 2. Schoenberger states that those ludic exhibitions had an oblique political stance. This is where “Dylaby” and Documenta 15 diverge. This edition of Documenta is defiantly political and critical of the very foundations of Western museums and institutions. And most importantly perhaps, the exhibition demonstrates the possibility of presenting art that is embedded in life rather that in the market or museum, both of which correspond with Western imperial structures.

Burleigh, “Ludic Labyrinths,” 6.

See →.

See Emmi Piker, “The Development of Movement-Stages”, The Pikler Collection, →.

ruangrupa states that art is rooted in life several times in their introduction in Documenta 15 Handbook ruangrupa, “Introduction,” Documenta 15 Handbook (Ostfilderm, Germany: Hatje Cantz Verlag, 2022). In this regard, it is also quite telling that chairs of Fridskul Common Library, which were produced by lumbung member collective El Warcha, echo Pikler’s triangle which she developed to teach children how to climb. This is yet another indication of RURUKIDS embeddedness in the exhibition discourse. Like Pikler’s infant, visitors, too, learn how to move through thirty-two exhibition venues scattered around Kassel.

See →. The sitcom is yet another echo of “Dylaby” in Documenta 15. Paula Burleigh has underlined that one of the clearest indicators of children’s involvement with “Dylaby” was a documentary film, narrated and led by a child, that demonstrates children’s willingness to participate in the exhibition and adults’ puzzlement with it. See Burleigh, “Ludic Labrythins,” 8. A similar strategy could be found in Roger M. Buergel and Ruth Noack’s documenta 12 (2007). In that exhibition, popular guided tours were led by children. See Anthony Spira, “Infancy, History and Rehabilition at documenta 12,” Journal of Visual Culture 7, no. 2 (August 2008): 228.

See Jack Zipes, Fairy Tales and Art of Subversion (New York: Routledge, 2006), 59–80. Agus’s work also recalls Francis Alÿs’s work The Nature of the Game for the Belgian Pavilion at the 59th Venice Biennale. In a recent interview about this work, Alÿs stated: “Adults tend to process traumatic experiences through speech. Children will do it through a play, and I thought this game was a beautiful example of how. To think that children are disconnected is wrong, they are actually very affected and connected and trying to make sense of what’s happening around them.” See →.

ruangrupa, “Introduction,” Documenta 15 Handbook (Ostfilderm, Germany: Hatje Cantz Verlag, 2022), 9.

Alva Nöe and J. Kevin O’Regan, “On the Brain-Basis of Visual Consciousness” in Vision and Mind: Selected Readings in the Philosophy of Perception, eds. Alva Nöe and Evan Thompson (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2002), 567.

Of course, Documenta 15 is not the first exhibition who led visitors to walk in the exhibition city. The list of such exhibitions would be endless, especially since the 1990s. What makes this edition of Documenta important is its insistence on children’s inclusion into meanderings that the exhibition charts. In this regard, it reminds the notion of “streetwork,” which was promoted by anarchists Colin Ward and Tony Fryson during 1970s and 1980s. Catherine Burke has stated that: “The notion of streetwork transformed environmental education into a radical urban form which envisaged children and young people as actively engaged resourceful responders to their immediate environment. An inspiration for Ward and Fyson was the fiction of Paul Goodman who developed the idea of the “exploding school” which realised the city as an educator.” See Catherine Burke, “Feet, footwork, footwear, and “being alive” in the modern school”, Paedagogica Historica 54 nos. 1/2 (2018): 41.