http://art.unm.edu/

Through mid-June, e-flux Education will focus its coverage on the United States, examining educational institutions in the American South and Southwest in particular. With attention paid to the specificities of each program or institution and its pedagogies, the upcoming features will also consider the surrounding regions’ dense legacies of segregation, slavery, and frontierism alongside more contemporary reformations of schooling, museology, and justice.

Ecology is a way of thinking about relationships in expansive, shared environments, while art frequently becomes understood as representing or “framing” things taken from the larger world. What can happen when those two realms of awareness and activity are integrated? Beyond a general “appreciation of nature,” how can such integrated realms of art and ecology be applied to areas that carry the highest stakes for both humans as well as the larger world?

Responses to the current legacy of Tewa communities and other Indigenous and land-based populations residing near the Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL), thirty-five miles northwest of Santa Fe, offers one example of art and ecology's integration. LANL is one of sixteen research and development laboratories operated by the US Department of Energy and one of the largest facilities of its kind in the world. Constructed under federal mandate in 1943, it served as the Manhattan Project’s headquarters after having displaced Tewa inhabitants and covered over ancestral graveyards. Members of the Tewa were the first victims of the project’s aggressive, ongoing experimentation with radioactive materials. Due to the radioactive materials that have since seeped into the region’s soil, water and air, generations of inhabitants have been contracting cancer at rates that exceed the national average. To this day, LANL still uses radioactive materials that off-gas volatile, toxic elements, and the laboratory ships those materials across Indigenous and shared territory near and far.

In nearby Albuquerque, the RAVEL Lab at the University of New Mexico has committed itself to studying the histories and legacies of the environment in and around Los Alamos. RAVEL is a component of the Art & Ecology program within UNM’s art department, and comprises a series of advanced, field-based courses. As an acronym, RAVEL remains open-ended: it is said to stand for “Radical Art ▽ Ecology Lab,” but also “Radicle Art & Vital Ecology Lab.” This type of flexibility is characteristic of the lab, which allows a diverse group of individuals and organizations to apply a wide range of methodologies to mutually generated projects. Led by UNM art department faculty, groups of students venture beyond the campus to specific sites and communities in order to engage with local issues and learn about ways to address them.

At the request of the Communities for Clean Water coalition and the Indigenous organization Tewa Women United (“wi don gi mu” in Tewa, or “We Are One”), UNM students participating in RAVEL’s spring 2025 iteration, led by Art & Ecology faculty Kaitlin Bryson and adjunct faculty Rachel Bordeleau, created an ethnographically sourced interactive map of the sites and routes in the Los Alamos region that have been contaminated by radioactive materials. The creative endeavor of the map doesn’t simply represent key geographical locations; it integrates community members’ real-life stories to produce a more dynamic cartography. Digital photographs of landscape and sky were overlayed with hand-painted images of native flora and fauna based on experiences shared by those community members. The process embodies crucial tenets of the Art & Ecology program and the RAVEL field studies courses, which emphasize, above all, creative engagement with the world outside the classroom. Students are expected to conduct substantial, focused research; develop technical facility in a range of expressive and communicative media; and, most fundamentally, invest substantially in getting to know local sites, communities, and stakeholders.

Still from a video made by students enrolled in “Healing Sacred Relations,” the spring 2025 RAVEL Lab in the Art & Ecology program at the University of New Mexico. Artists: Fin Martens, AM Darka, Lila Steffan, Luc Biscan-White. Courtesy of Kaitlin Bryson.

“I would say relationships are the medium,” asserted Bryson, RAVEL’s co-director, when asked to describe the lab. De-emphasizing specific materials, genres, or techniques. creative processes and outcomes developed in RAVEL are instead generated through real-world connections. As a graduate student at UNM, Bryson found in Art & Ecology an unusually supportive context in which to weave together her interests in agroecology and art. Bryson began working with Tewa Women United during her graduate thesis work at UNM between 2015 and 2018, and in 2023 she returned to UNM to serve as a faculty member and to spearhead RAVEL alongside Art & Ecology professor Jeanette Hart-Mann. Bryson’s insight about relationships points to a principal feature of RAVEL. The lab’s emphasis on relationality leads to the development of curricula and courses that are ecosocial to the core, reflecting RAVEL’s commitment to generating and implementing project ideas in response to long-developing relationships with communities and individuals who activate faculty expertise and student interests and needs. Emphasizing the role of the most recent cohort, co-director Hart-Mann has stated: “the students really are in the midst of making [RAVEL] what it will be.”

Such approaches can trace their roots to former faculty member Basia Irland’s teachings in UNM’s department of art in the 1980s and ’90s. Irland emphasized getting students out of the classroom and the studio and into the “field” of greater New Mexico. Irland’s initiative led to the development of one of the very first academic programs in the country dedicated to deep engagement with art and ecological concerns—one that also works with students and experts in other disciplines, such as biology and hydrology. Art & Ecology remains one of a small contingent of programs that integrate the two disciplines worldwide.

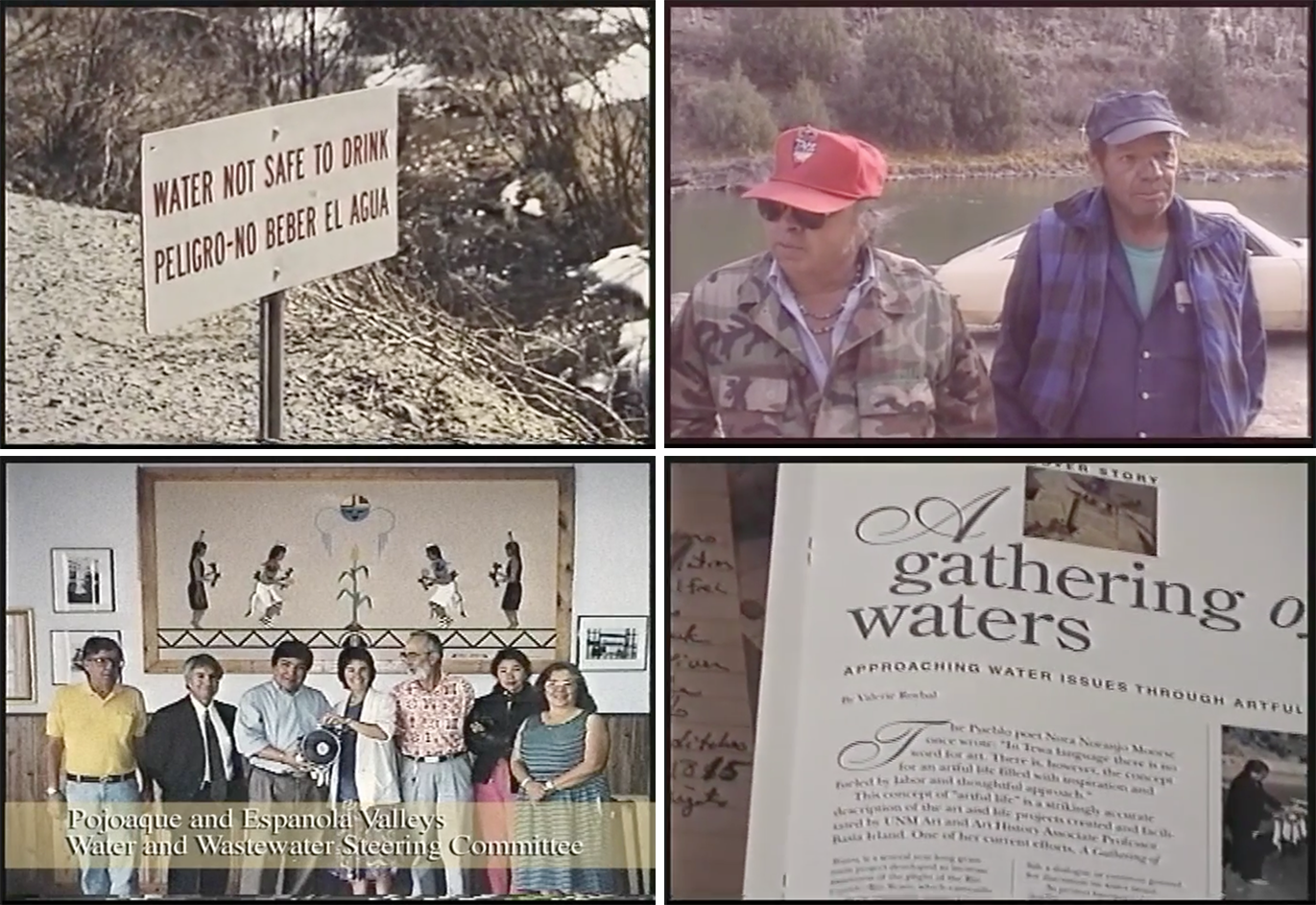

Irland’s own work, which centers around waterways, culminated most recently in the book What Rivers Know (Texas A&M University Press, 2025). Crafting twenty-five “first-person accounts” on behalf of rivers around the world, Irland represents our rapidly changing world from each river’s point of view. In her 1995 documentary film A Gathering of Waters, Irland distilled aspects of a five-year-long project in which she led students in collaborative, community-based activities along the length of the Rio Grande with the goal of enhancing public understanding of the river’s relationship to culture and the environment.

Art & Ecology’s field-based, community-oriented, site-specific approach also grew out of an earlier incarnation of RAVEL. In 2000, UNM fine art faculty Bill Gilbert and John Wenger founded the Land Arts of the American West (LAAW) program, which from its outset has promoted field- and place-based practices that directly engage with non-classroom locations. In his 2019 book Arts Programming for the Anthropocene: Art in Community and Environment, co-authored with Anicca Cox, Gilbert recounts how extended interactions with Indigenous potters which illuminated their reliance on locally sourced materials, and the intimate relationships they cultivate with the sites from which they procure them, were essential to the development of his own teaching methods at the university. His process included negotiating with and educating administrators back at UNM as well as navigating complex political and physical issues, including disputes among different Indigenous factions about access to reservations, governmental administration of private and public lands, and working with limited resources.

Mary Lewis Garcia, the inheritor of a long line of ancestral Indigenous pottery practices centered around Acoma Pueblo, sixty miles west of Albuquerque, played a central role in teaching Gilbert and early LAAW classes about cultivating relationships to specific environments and imparting material and technical knowledge. This sharing of cultural attitudes and approaches was vital in moving the LAAW initiative beyond the technical and studio-based instruction at UNM and toward hands-on research and direct interactions with community members outside of the campus. These engagements advanced from weekly, daylong, on-site classes to full semester courseloads (equivalent to four classes or twelve academic credits) that could support extended encounters.

In his book, Gilbert marked a shift beginning in 2009:

LAAW entered a new path towards arts activism and social practice in which artist, artwork, community, and audience all began to commingle…LAAW has gone on to complete a series of projects in which community members are co-creators of the artworks and the community is both the venue for presentation and the audience. In trying to flesh out the central drivers of environmental and social issues in our bio-region, we have so far explored the following interrelated themes: Foodshed, Utopian Architecture, United States/Mexico Border, Rio Grande Watershed, and Environmental and Social Justice.[footnote Bill Gilbert and Anicca Cox, Arts Programming for the Anthropocene: Art in Community and Environment (Routledge, 2019), 136.]

The long, winding trajectory from Irland’s initial program to Gilbert’s overlapping yet distinct objective took a new turn in 2014, when Hart-Mann became director of LAAW. Hart-Mann, who is a co-founder of the artist collective SeedBroadcast, has helped reconceptualize the program as RAVEL. This transition has enabled a growing emphasis on activism and ecosocial orientation within the program’s methodologies and concentrations.

Stills from Basia Irland, A Gathering of Waters: The Río Gande, Source to Sea, 1995–2000.

RAVEL’s semester-long themes have included extractivism, migration and incarceration, agroecology, and ecological restoration. The program considers how these issues impact waterways, land, and living forms, and how shared ecosystems might be differently reshaped through deliberate creative interventions. RAVEL’s 2024 fall iteration, Seeding Radicle Futures, converged situated plant ecologies and the prison-industrial complex. Hart-Mann and Bryson led a class in developing a seed library to include as a component of the Mobile Abolition Library initiated by the formerly incarcerated local artist sherry crider. The library traveled around the state to areas with mass incarceration sites—including Grants, Crownpoint, and Las Cruces. As a series of mobilizing actions, diverse ecoregional seeds were distributed as both literal and metaphorical means of healing, community resilience, and revitalization, while also underscoring issues such as food justice and the growing impacts of wildfires.

As in all RAVEL field-based projects, students explored these larger themes using their own unique media and methodologies. One Seeding Radical Futures student focused intensively on a single plant species that they encountered during fieldwork aided by the Institute for Applied Ecology, another partner organization; another student who had previously worked with incarcerated individuals addressed issues associated with that part of the course’s themes. As an additional creative outcome, RAVEL held a public film festival of student-generated work at the Jean Cocteau Theater in Santa Fe in the fall of 2024.

The kinds of prior experience that have led students to Art & Ecology and RAVEL are varied. billy von raven, who graduated in May 2025, says he entered UNM’s graduate Art Studio program after pursuing painting at the University of Oregon. During his undergraduate studies, von raven recalled: “[I] stubbornly insisted on gathering a bunch of trash that I had gathered in the watersheds of the area […] and embedded them into a piece that I used fibers to connect to and lead the viewer out of the art gallery into the river.” Agricultural experience in New Mexico connected him to its larger landscape while pointing him toward UNM as a context in which to continue graduate studies. While at UNM, von raven participated in another RAVEL project led by Hart-Mann in 2022 that worked with Borderlands Restoration Network (BRN) in Arizona. In keeping with RAVEL’s and Art & Ecology’s commitments to creatively engage across disciplinary borders, von raven collaborated with a farmer and another UNM graduate student working in theater.

During that 2022 project, the cohort of RAVEL students camped on BRN land, met with community partners daily, and participated in restoring watershed habitat. Asked for details on those processes, von raven responded: “We employed a method called induced meandering, informed by Indigenous methods, which uses rock and wood structures to slow down water and reduce erosion. With BRN and In the Manzano Mountains with Cameron Weber of Rio Grande Return we helped build rock structures from local rocks, such as Zuni bowls, one-rock dams, and media lunas in streambeds in order to support water infiltration into the soil, increase vegetation cover, and reduce habitat loss.”

Marisa Demarco, Dylan McLaughlin, and Jessica Zeglin, There must be other names for the river, 2021. Courtesy of the artist.

RAVEL participants learned about how plants follow human migrations patterns across borders—“because seeds move,” as Hart-Mann put it, “plants move, right?” The course’s emphasis on rewilding thus intersected with social justice work, resulting in creative outcomes that included performance, film, and sound-based workshops drawing on the immediate environment. Attention to sound was inspired by Szu-Han Ho, another art department faculty member who has taught courses in deep-listening responsiveness as well as classes challenging naturalized ideas of borders (e.g., “Politics of Performance”), which are also foci in Ho’s own artistic projects.

The Art & Ecology program is “very accountable and real, for those who want to be in a community that isn’t pretentious but will push you,” says Dylan McLaughlin, a Diné artist who graduated from the art department in 2022. It’s a set of attitudes, which, he asserts, “is passed down through the curriculum.” McLaughlin credits the professors at UNM for pronounced commitments to community engagement and real-world politics. He relished the program’s academic, conceptual, and ethical rigor, and how it engendered critical thought about creative practice and its political outcomes while also interrogating material, linguistics, and research methods.

Art & Ecology was also generative and supportive, McLaughlin added, and he appreciated the opportunities to collaborate with an exceptionally large and diverse graduate cohort, to work within large studio spaces and extensive technical facilities, and to experiment. This combination generates a lot of critical care for participants’ work in the program—something that continues to be reflected in McLaughlin’s work. One such outcome, There must be other names for the river (2021), McLaughlin’s collaborative waterway sound-mapping work with Marisa Demarco and fellow RAVEL and Art & Ecology alum Jessica Zeglin, was featured in the exhibition Going With the Flow: Art, Actions, and Western Waters at SITE Santa Fe in 2023.

There must be other names for the river merges artistic praxis and environmental engagement while building greater bonds, person-to-person as well as between people and the world. Such convergence is still relatively rare in the worlds of art and its education. RAVEL and UNM’s Art & Ecology program stand out for the rich substrate of relationships they foster in many ways: by bringing humans together to develop shared projects, by encouraging thoughts and conversations that strengthen community ties, and by reminding people of our living bonds with the land, water, air, and other creatures. The answers to my opening questions are embodied in the ongoing, sustained partnership between participants in UNM’s RAVEL, Art & Ecology, and members of the Tewa community as they catalyze human creative collaboration in their attempt to reshape public policy on radioactive materials. None of that would happen without the recurring, sustained commitment to work together.

Bill Gilbert and Anicca Cox, Arts Programming for the Anthropocene: Art in Community and Environment (Routledge, 2019), 136.