March 27, 2015, 12am

e-flux and Sternberg Press, with lectures and presentations by Alexander Galloway, Karen Archey, and Zach Blas.

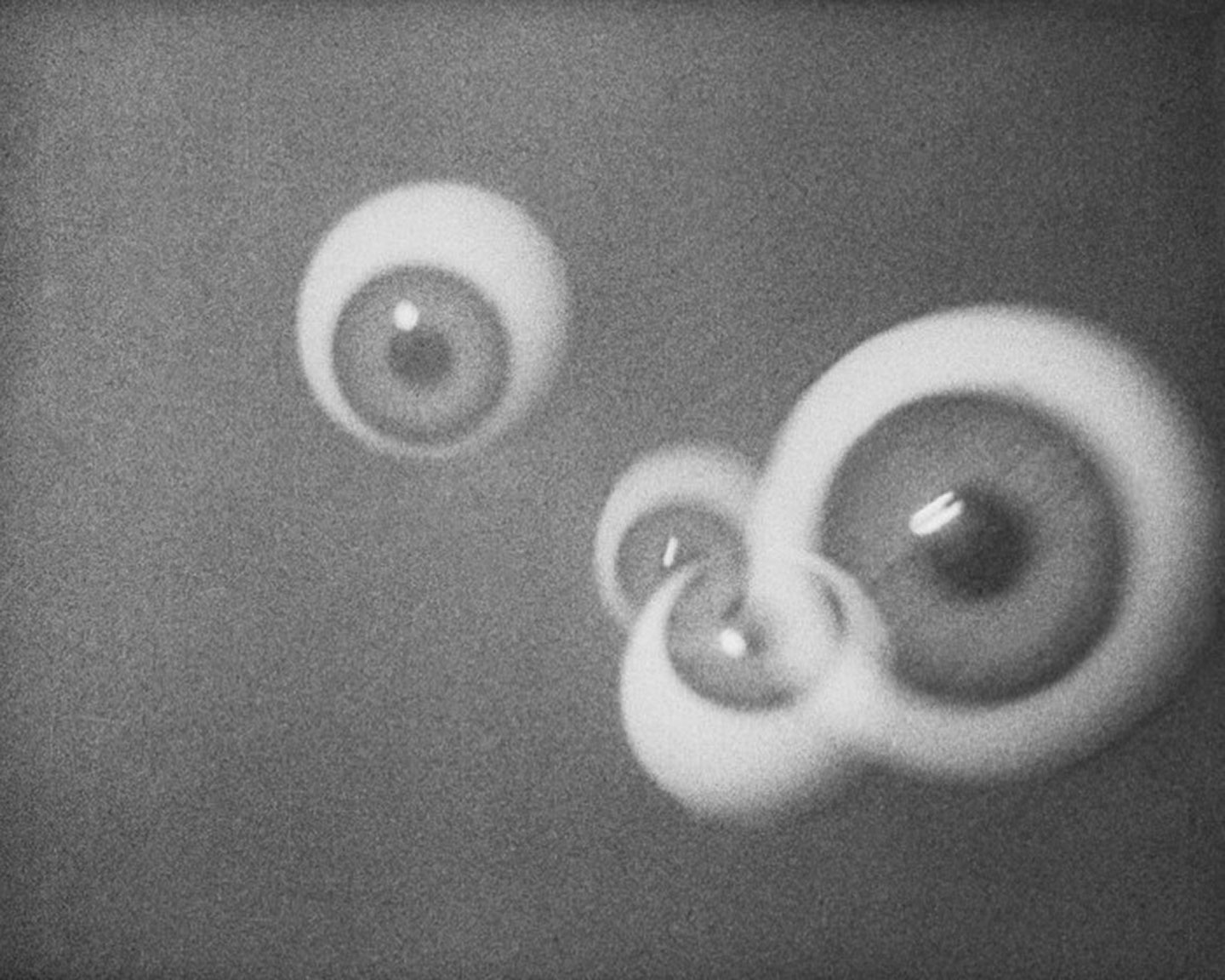

The internet does not exist. Maybe it did exist only a short time ago, but now it only remains as a blur, a cloud, a friend, a deadline, a redirect, or a 404. If it ever existed, we couldn’t see it. Because it has no shape. It has no face, just this name that describes everything and nothing at the same time. Yet we are still trying to climb onboard, to get inside, to be part of the network, to get in on the language game, to show up on searches, to appear to exist. But we will never get inside of something that isn’t there. All this time we’ve been bemoaning the death of any critical outside position, we should have taken a good look at information networks. Just try to get in. You can’t. Networks are all edges, as Bruno Latour points out. We thought there were windows but actually it’s made of mirrors. And in the meantime we are being faced with more and more—not just information, but the world itself. And a very particular world that has already become part of our consciousness. And it wants something. It doesn’t only want to harvest our eyeballs, our attention, our responses, and our feelings. It also wants to condition our minds and bodies to absorb all the richness of the planet’s knowledge.

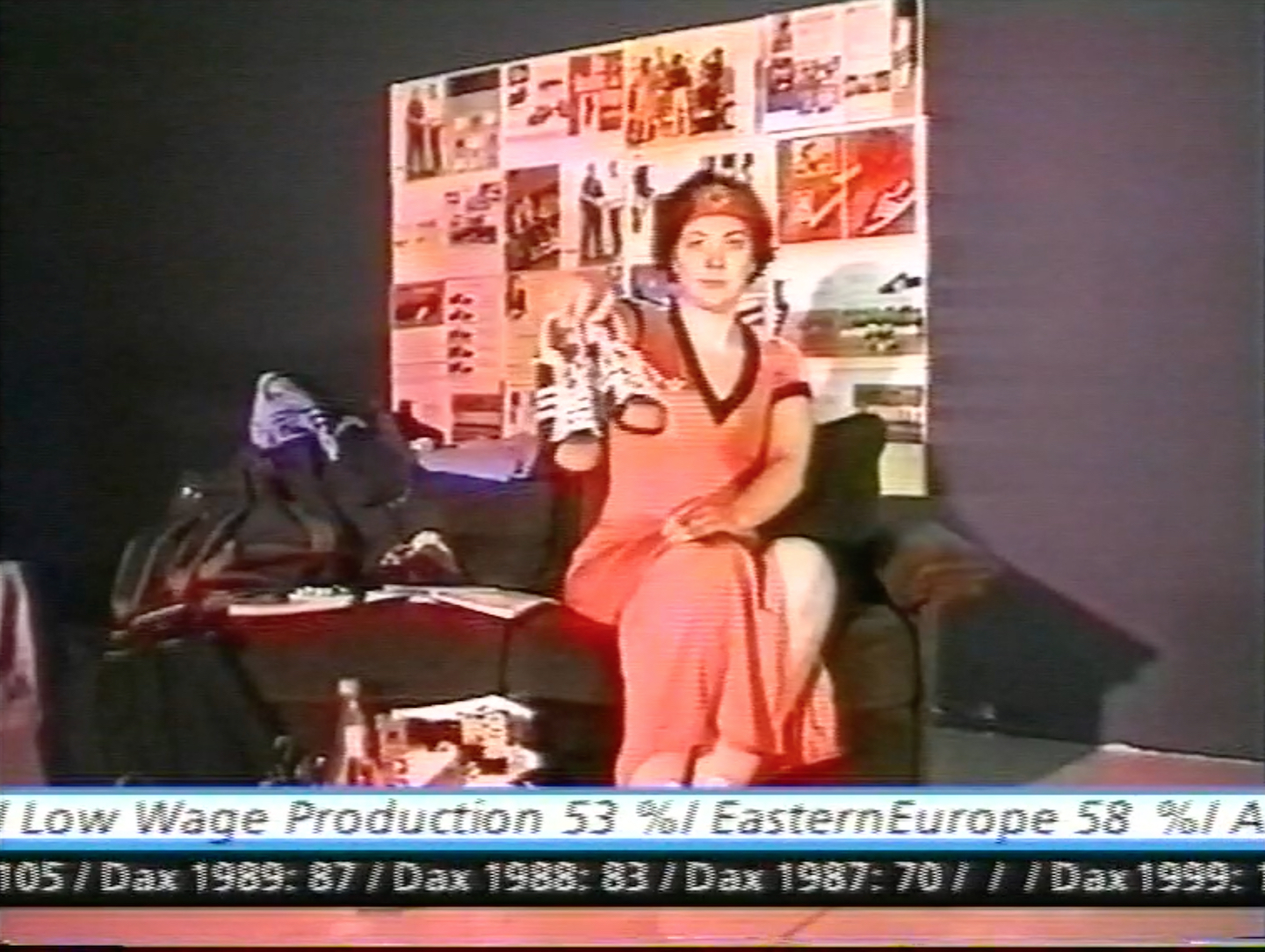

There is something we used to call the internet that had an infrastructural base. And it worked a bit like its unconscious, storing all the things the glowing promises of free flow must repress in order to function. Looking under the hood, it turns out that its infrastructure was mostly based in the United States, mostly owned and operated by the United States. It was ARPANET that implemented the first successful packet switching network for the US Department of Defense in the late 1960s. From there the nodes slowly grew throughout the ’70s and ’80s until the network was decommissioned in the early ’90s to make way for commercial internet service providers. Even though significant parts of the regulatory infrastructure over information exchange still falls under the oversight of the US government, whether directly or indirectly, the real shift in the 1990s came in realizing the commercial and economic potential of information exchange, placing it at the center of the era of globalization and acceleration in the financial sector.

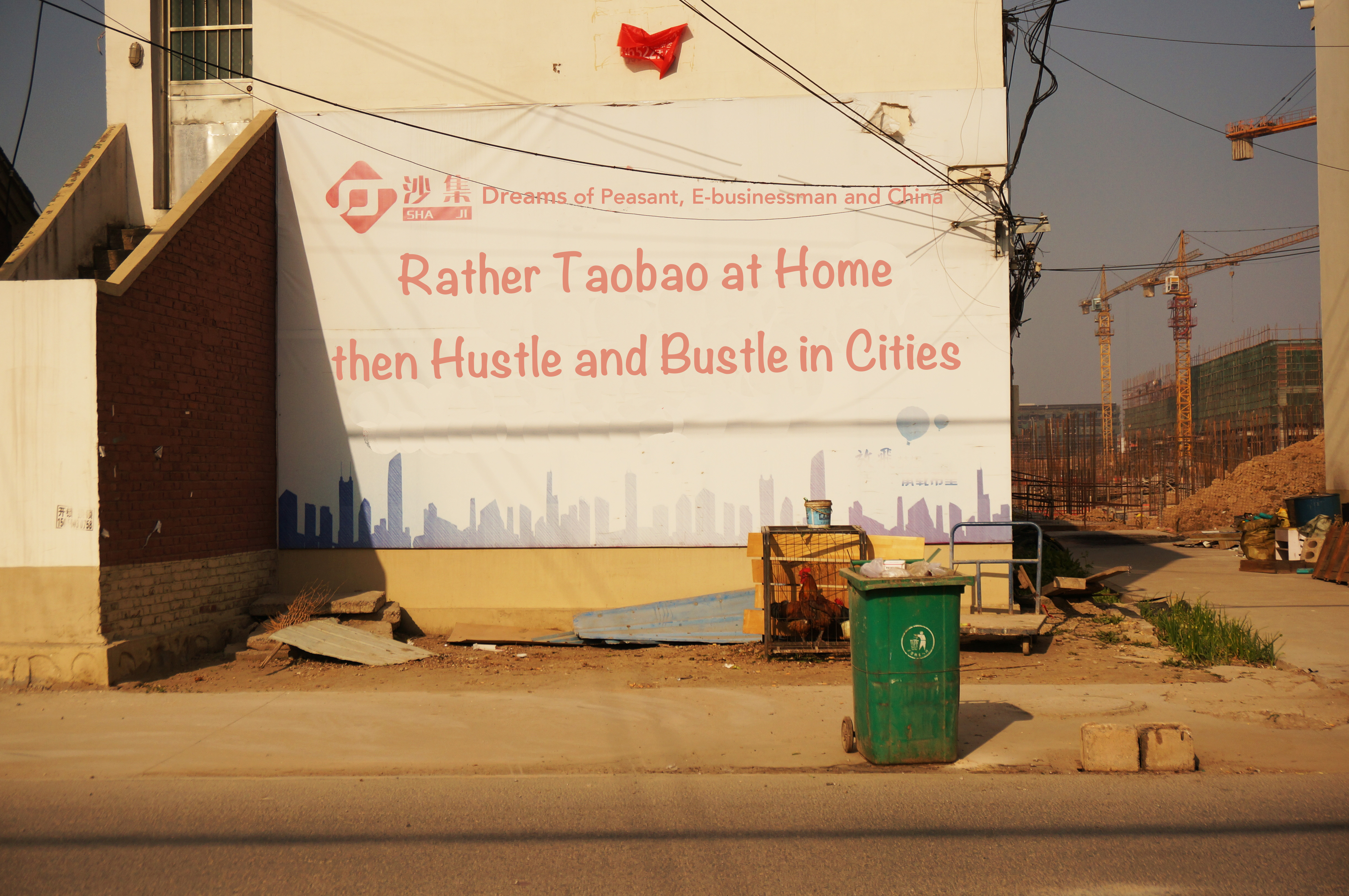

It is strange to think how, in spite of so many young artists now playing with digital aesthetics, it was actually Warhol who saw it coming most clearly. The massive shift from depth to surface that Warhol explained with celebrity culture and advertising has now taken hold of language itself and spread across the planet. It’s no wonder that since the 1990s the political, social, and economic aspects of artistic production have become increasingly interchangeable and hard to distinguish from one another. Planetary networks have become places of profound confusion and dislocation. We know from the start that we probably won’t find what we’re looking for, so we learn to search sporadically and asymmetrically just to see where we end up. This might look and feel like drifting, and traditional or conservative notions of substance will always try to dismiss its noise, its cat videos and porn, bad techno and bombastic contemporary art, but one should be careful not to underestimate the massive distances being crossed in the meantime.

These distances are themselves very quickly reformatting our consciousness and cognitive capacity to absorb entire worlds made of contradiction—not only in language but far beyond language as well. Some people might already be there: scammers and tricksters, the frazzled post-studio artist and the post-institutional independent militia, political dissidents and unruly journalists who know never to trust their maps. They know that contradictions don’t resolve, rather you surf across them using empathy and solidarity, emotional blackmail, jokes, pranks, and vanguardism as norm. Our ability to traverse these contradictions may very well become the backbone of the global telecommunications network we used to think was an internet.

Edited by Julieta Aranda, Brian Kuan Wood, Anton Vidokle

With texts by Hito Steyerl, Keller Easterling, Bruno Latour, Ursula K. Heise, Gean Moreno, Franco “Bifo” Berardi, Diedrich Diederichsen, Rasmus Fleischer, Jon Rich, Geert Lovink, Brian Kuan Wood and Joana Hadjithomas / Khalil Joreige, Hans Ulrich Obrist and Julian Assange, Metahaven, Benjamin Bratton, and Patricia MacCormack

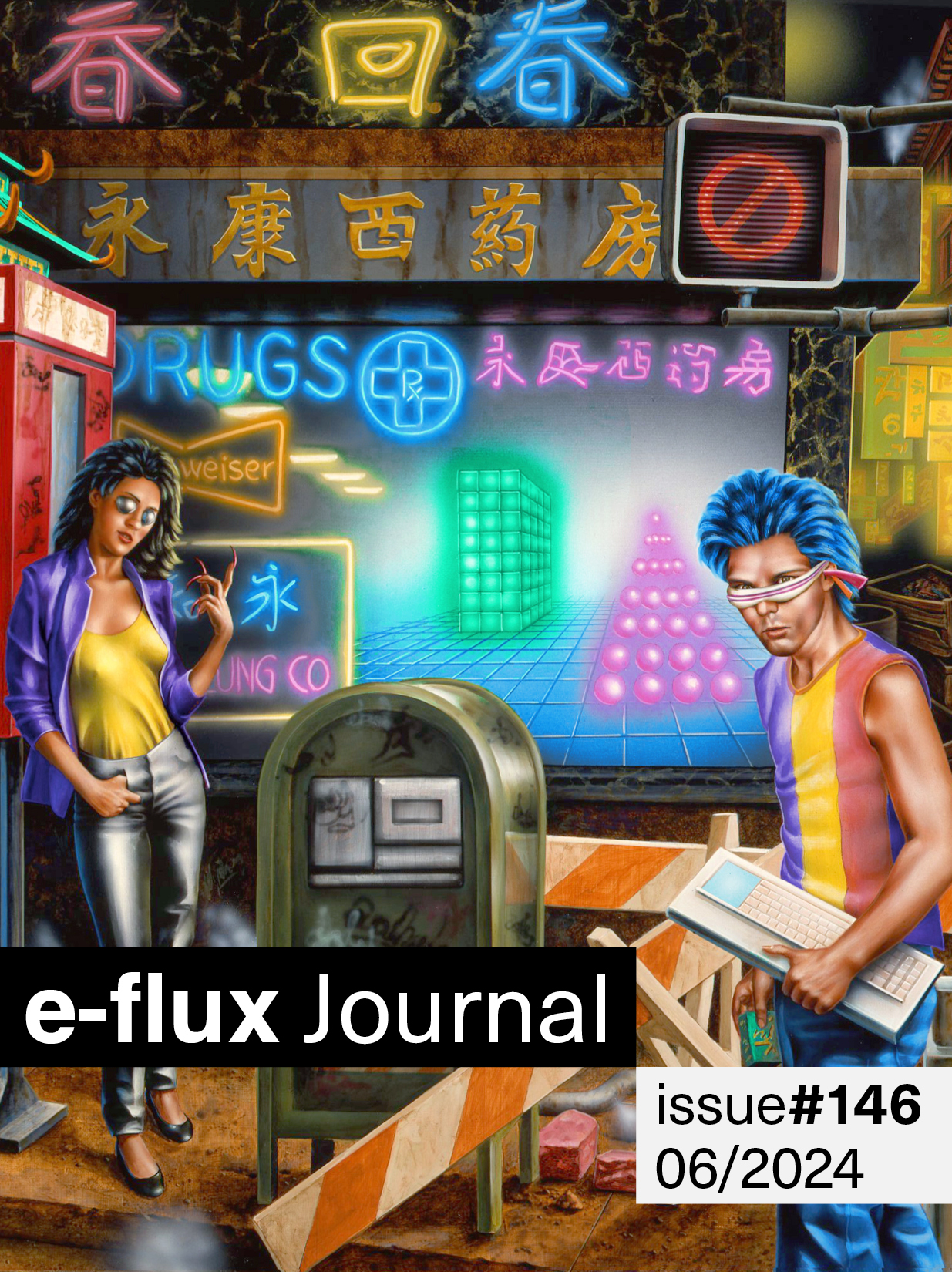

Other titles in the e-flux journal reader series:

Jalal Toufic, Forthcoming (2014)

Martha Rosler, Culture Class (2013)

Hito Steyerl, The Wretched of the Screen (2012)

Moscow Symposium: Conceptualism Revisited (2012)

Are You Working Too Much? Post-Fordism, Precarity, and the Labor of Art (2011)

Boris Groys, Going Public (2010)

What is Contemporary Art? (2010)

e-flux journal reader 2009 (2009)