May 10, 2013, 12am

On April 7, 1979, a number of militants and intellectuals, formerly members of Potere Operaio (Workers Power) and Autonomia Operaia, were arrested across Italy on charges of terrorism. They were accused of being leaders of the armed organization the Red Brigades, and for the kidnap and execution of Aldo Moro. As head of the governing Christian Democratic Party, Moro was on the eve of successfully engineering a “historic compromise” between the Christian Democrats and the Italian Communist Party. Evidence to support the prosecution was, and remains unfounded, yet the majority of the prosecuted were held in preventative prison from 1979 until the trial’s close in 1984. It is this 1982–84 trial that artist Rossella Biscotti takes as her point of departure for the performance and exhibition The Trial at e-flux.

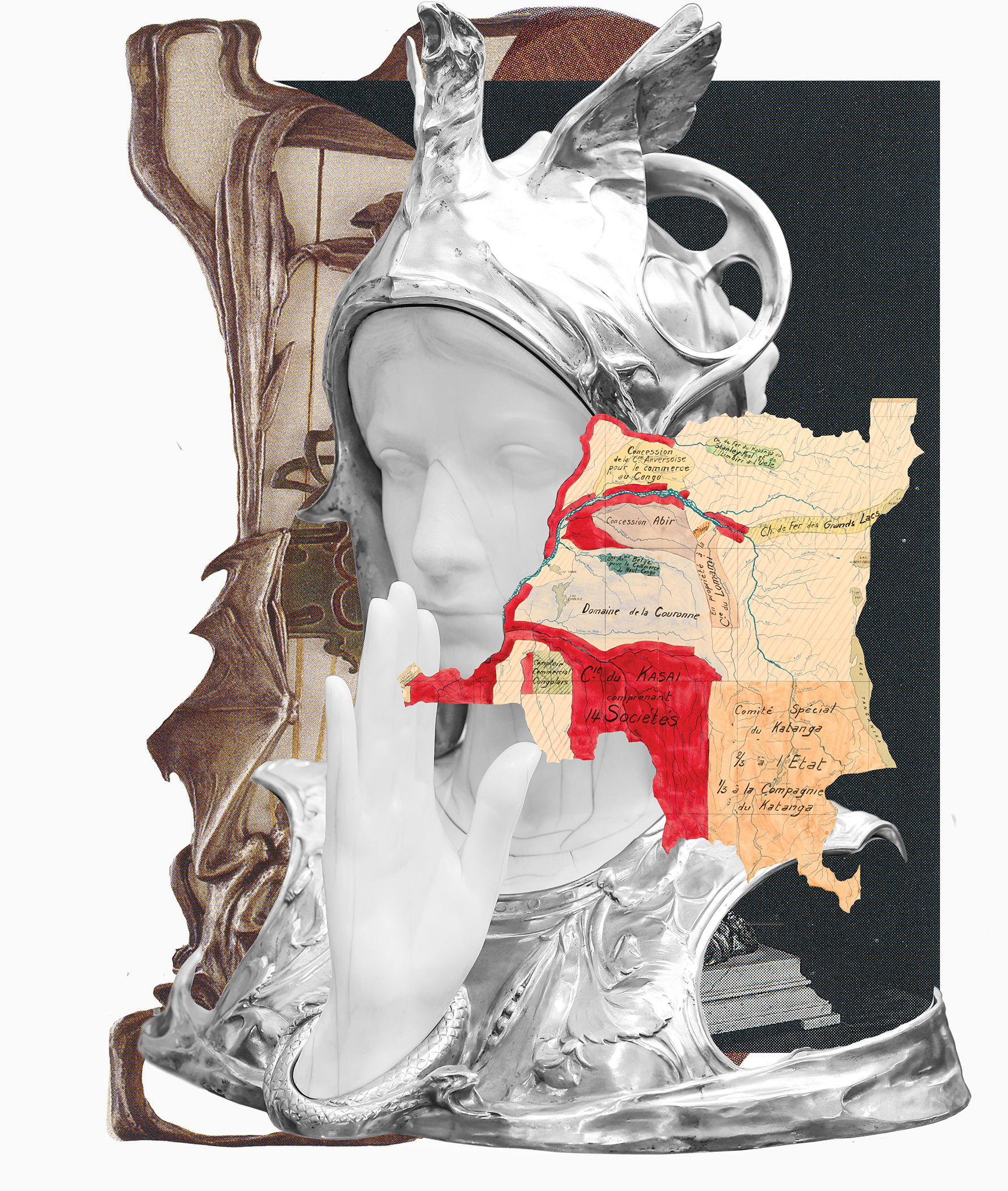

The core of The Trial is a six-hour audio edit of the original courtroom recordings. Initiating the show on May 11 and 12 is a two-day simultaneous live translation of this sound piece from Italian to English. The act of translation is central to the exhibition, as both a transferral and an embodiment of the historical trial’s language within the present time. Projected on the wall is a black and white silent film that traces a performance held in the high-security courthouse, designed by rationalist architect Luigi Moretti in 1934, in which the trials took place. Remnants taken from the courtroom, wooden benches and keys, are present in the exhibition, activating the history of the courthouse building. A series of red silkscreen prints are hung on the wall, and documentation of previous translation performances are on view. Over the course of the exhibition, Biscotti, Yates McKee, (co-editor of the magazine Tidal: Occupy Theory, Occupy Strategy), and special guests will co-facilitate a reading group devoted to the historical legacies of Autonomist Marxism relative to recent struggles including but not limited to those affiliated with Occupy.

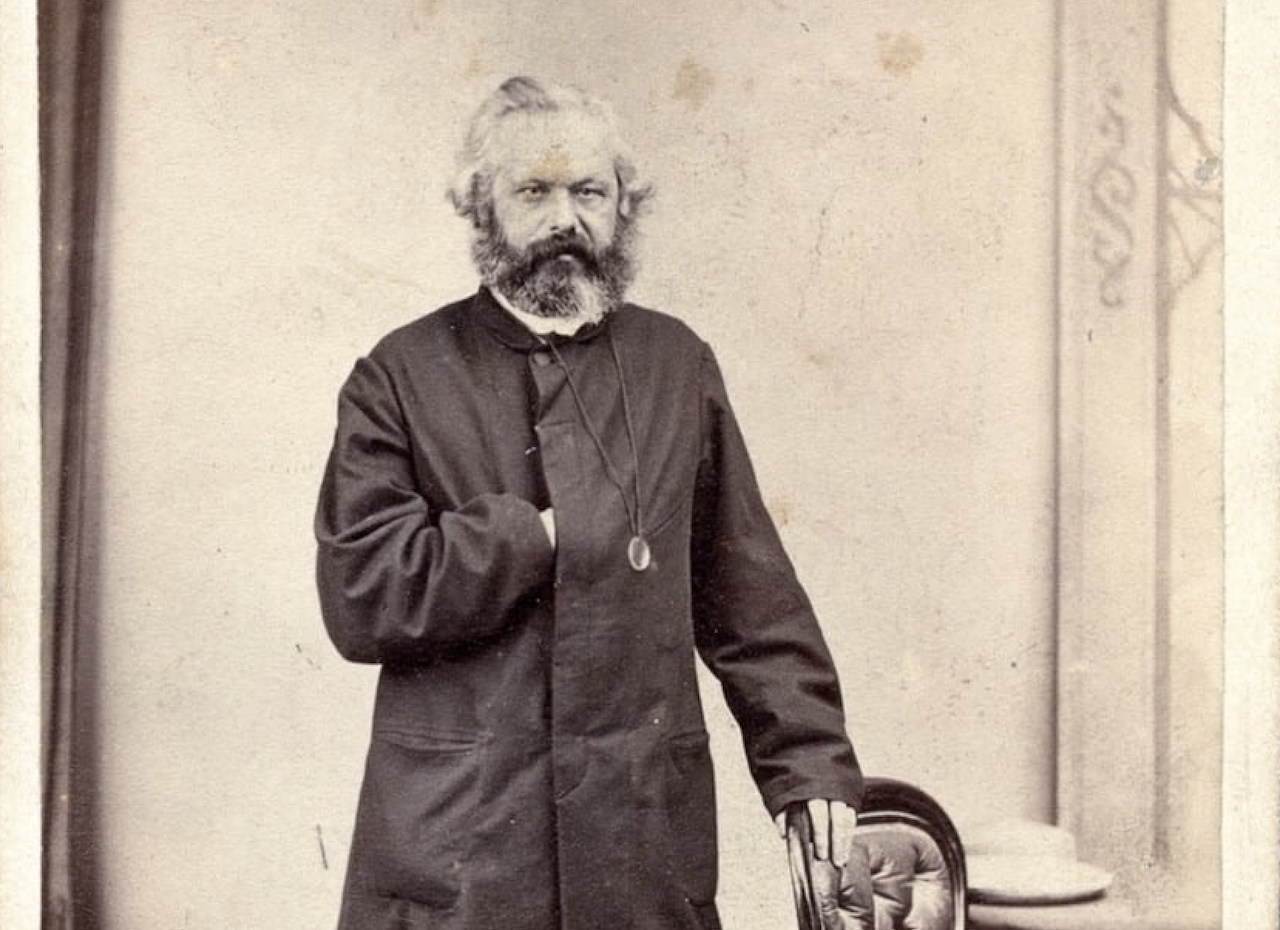

The Trial must be situated within the period of social and political unrest experienced by Italy beginning with its rise in economic productivity following World War II. Before its dissolution in 1973, the Potere Operaio movement was influential in pushing for an alliance between the libertarian student protests of 1968 and the autonomous workers movement of 1969. This formed the backdrop against which Autonomia Operaia would emerge in the mid-1970s as a rhizomatic network of intellectuals throughout Italy. The thinkers of the Italian autonomia movement were the first to recognize a massive integration of labor, exploitation, and creativity that artists around the world continue to grapple with today. In unfurling a decisive moment in its history, Rossella Biscotti reminds us that our work still happens within a political project, even if its name is not apparent.

Rossella Biscotti was born in 1978 in Molfetta, Italy. She has had solo exhibitions at the CAC Vilnius (2012), Fondazione Galleria Civica di Trento (2010), and the Nomas Foundation, Rome (2009), and participated in group exhibitions at dOCUMENTA (13), Kassel (2012), Manifesta 9, Genk (2012), MAXXI National Museum for 21st Century Art, Rome (2010–11), Witte de With, Rotterdam (2010), and Museu Serralves, Porto (2010). Biscotti received the Premio Italia Arte Contemporanea Award in 2010. Biscotti will participate in the forthcoming Venice Biennial 2013 and has a solo exhibition at the Wiener Secession opening in July 2013.

Rossella Biscotti and e-flux would like to thank: Arianna Bove, Kevin van Braak, Danilo Correale, Kelman Duran, Chicco Funaro, Michel Hardt, Lily Lewis, Louis Luthi, Rossana Miele, Max Mosca, Timothy Murphy, Nick Mirzoeff, Toni Negri, Alessandra Renzi, Wilfried Lentz, Toon de Zoeten, all the defendants of the April 7 trial, and Radio Radicale for the original recordings.

For further information please contact laura@e-flux.com.