November 11, 2016, 12am

Minneapolis 55403

United States

e-flux and Walker Art Center present Avant Museology, a symposium exploring the practices and sociopolitical implications of contemporary museology, and taking place this November in two parts: at the Brooklyn Museum and at the Walker Art Center.

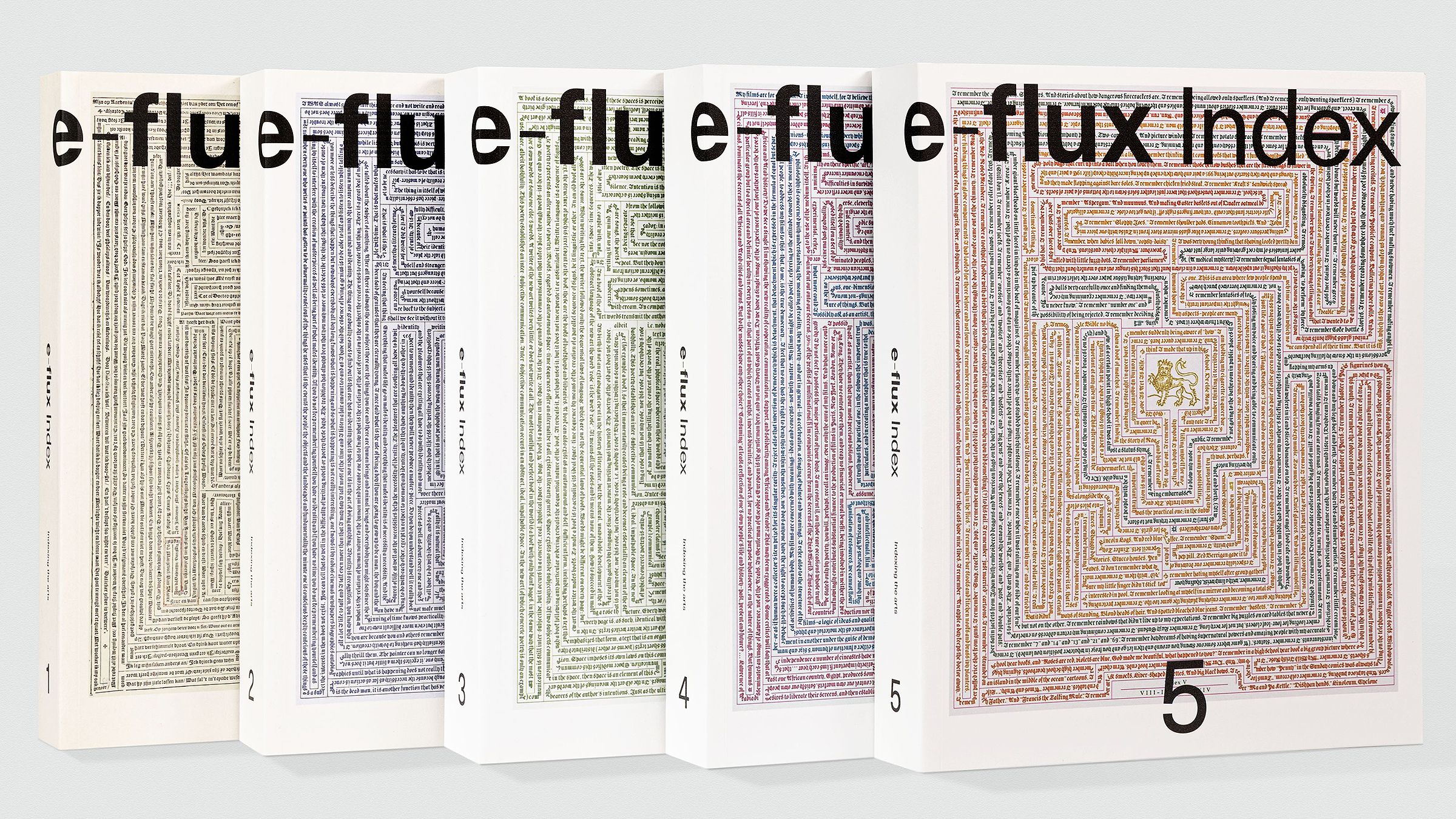

The symposium is based on the book Avant-Garde Museology, edited by Arseny Zhilayev, published by e-flux, and distributed by the University of Minnesota Press.

November 11-12 | Avant Museology at Brooklyn Museum

Brooklyn, NY

With Bruce Altshuler, Lynne Cooke, Kimberly Drew, Liam Gillick, Boris Groys, Juliana Huxtable, Fionn Meade, Molly Nesbit, Hans Ulrich Obrist, Anne Pasternak, Nikolay Punin, Irene V. Small, Nancy Spector, Anton Vidokle, Fred Wilson, Arseny Zhilyaev.

*RSVP and more information on the Brooklyn Museum program here.

November 20-21 | Avant Museology at Walker Art Center

Minneapolis, MN

With Jonathas de Andrade, Claire Bishop, Adrienne Edwards, Boris Groys, Ane Hjort Guttu, Wayne Koestenbaum, Nisa Mackie, Fionn Meade, Sohrab Mohebbi, Timothy Morton, Elizabeth Povinelli, Walid Raad, Hito Steyerl, Anton Vidokle, Cary Wolfe, Arseny Zhilyaev.

*Co-presented by the Walker Art Center, e-flux, and the University of Minnesota Press. Tickets and more information on the Walker Art Center program here.

Taking its cue from the recently published book Avant-Garde Museology, the symposium will address the memory machine of the contemporary museum vis-à-vis its relationship to the contemporary artistic practices, sociopolitical contexts, and theoretical legacies that shape and animate it. Where the museum may have once been a mere container for objects and ephemera, the mutability of the contemporary museum has facilitated the apparently seamless absorption of its own complex histories, paradoxical political and socioeconomic functions and ideas. It begs the question: Can contemporary museology be invested with the energy of the visionary and political projects contained in the works that it circulates and remembers?

The museum of contemporary art might very well be the most advanced recording device ever invented in the history of humankind. It is a place for the storage of historical grievances and the memory of forgotten artistic experiments, social projects, or errant futures. But in late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Russia, this recording device was undertaken by a number of artists and thinkers as a site for experimentation. Edited by Arseny Zhilyaev, Avant-Garde Museology documents the progressivism of the period, with texts by Aleksandr Bogdanov, Nikolai Fedorov, Kazimir Malevich, Andrey Platonov, Aleksandr Rodchenko, and many others—several of which are translated into English for the first time. At the center of much of this thought and production is a shared belief in the capacity of art, museums, and public exhibitions to produce an entirely new subject: a better, more evolved human being. And yet, though the early decades of twentieth-century Russia have been firmly registered in today’s art history as a time of radical social and artistic change, the uncompromising and often absurd ideas in Avant-Garde Museology appear alien to a contemporary art history that explains suprematism and constructivism in terms of formal abstraction. In fact, these works were part of a far larger project to absolutely instrumentalize art and its rational capacities and apply its forms and spaces to a project of uncompromising progressivism—a total transformation of life by all possible means, whether by designing architecture for life in outer space, developing artistic technology for the resurrection of the dead, or evolving new sensory organs for our bodies.

Today, it is hard to deny the similarity between the bourgeois museum and the contemporary liberal dogmas of open-ended contemplation and abstract self-realization that guide curatorial and museum culture since the dismantling of the Soviet Union in the 1990s. This symposium will investigate the social and artistic decisions of a critical period of left politics as well as contemporary museological culture. In shedding this light, an explicit question suddenly emerges: Under a regime in which social experiments and upheavals become abstract formal gestures, what has the political application of historical memory become?

Perhaps the museum of contemporary art already serves this purpose. Consider what Nikolai Fedorov wrote in the 1880s: that the ultimate function of the museum is to unify progressives and conservatives, vitality and death: “And our age in no way dares to imagine that progress itself would ever become the achievement of history, and this grave, this museum, becomes the reconstruction of all of progress’s victims at the time when struggle will be supplanted by accord, and unity in the purpose of reconstruction, only in which parties of progressives and conservatives can be reconciled—parties that have been warring since the beginning of history.”