On Duchamp's studio in relation to his readymades, see Helen Molesworth, "Work Avoidance: The Everyday Life of Marcel Duchamp's Readymades," Art Journal 57 (1998): 50-61.

Marcel Duchamp to Suzanne Duchamp, 15 January 1916, in Affectionately Marcel: The Selected Correspondence of Marcel Duchamp, ed. Francis Naumann and Hector Obalk (London: Thames and Hudson, 2000), 43.

Duchamp did try to expose them in a more public manner: there were two readymades that he hung in the umbrella-stand area at the entrance of the Bourgeois gallery in New York in April 1916, which went totally unnoticed and then, a year later, there was the ill-fated submission of Fountain to the Society of Independent Artists Exhibition, where it remained completely hidden behind a partition and subsequently lost.

Molesworth, "Work Avoidance," 50.

Duchamp to Walter Arensberg, 8 November 1918, in Affectionately Marcel, 64.

Duchamp to Jacques Doucet, 19 October [1925], in Affectionately Marcel, 152.

Duchamp to Dreier, 11 September 1929, in Affectionately Marcel, 170.

The 1936 Exposition Surréaliste d'Objets, held in the Parisian apartment-gallery of African-artifact dealer Charles Rattan, was an important precedent for the Surrealist movement's thinking about the presentation of art. The 1938 Exposition Internationale du Surréalisme remains, however, the beginning of a striking extension of this concern and the first real Surrealist recasting of the space and architecture of display. Surrealism's ideological concerns influenced the tenor of the displays in which they were involved, thus the treatment of these exhibitions here is by definition partial, focusing as it does mostly on Duchamp's role.

Among these are the three who provide the most thorough descriptions of the event by its participants: Georges Hugnet "L'exposition Internationale du Surréalisme," Preuves 91 (September 1958): 38-47; Marcel Jean, with the collaboration of Arpad Mezei, Histoire de la peinture surréaliste (Paris: Seuil, 1959), 280-89; and Man Ray, Autoportrait, trans. Anne Guérin (Paris: Éditions Robert Laffort, 1964), 205-6; 243-44.

Jean, Histoire, 281-82.

Whereas someone like Robert Delaunay grounded his color researches in the precise exploration of the scientific laws of Hermann von Helmholz or the writings of Michel-Eugène Chevreul and his "Law of the Simultaneous Contrast of Colors," Duchamp's sensory explorations – even in their most seemingly (mockingly) scientific moments – were more about looking in its dense ideological, institutional, psychological, and physico-erotic dimensions, aspects largely ignored by his artist-contemporaries. In her sustained work on Duchamp's optic games, Rosalind Krauss has, extending the analysis of Jean-François Lyotard, underlined the ways in which the artist's vision experiments and optical illusions work to "corporealize the visual," offering themselves as counters to those very notions of good form and pure opticality central to aesthetic Modernism. See, in particular, Krauss, "The Im/pulse To See," in Vision and Visuality, ed. Hal Foster (Seattle: Bay Press, 1988), 51-75; and Kraus, "The Blink of an Eye," in The States of 'Theory': History, Art, and Critical Discourse, ed. David Carroll (New York: Columbia University Press, 1990), 175-199. See also Lyotard, Les TRANSformateurs DUchamp (Paris: Galilée, 1977).

Duchamp speaks about the exhibition preparation, the string purchase, and the spontaneous combustion of the first webbing of string in his interview with Harriet, Sidney, and Carroll Janis, 1953. Typescript, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Duchamp Archives; and see also: Pierre Cabanne, Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp (London: Thames and Hudson, 1971), 86.

One might read the exhibition's particular orchestration of vision and the positioning of the visitor as an instance of Duchamp's ongoing exploration of perception and the manipulation of looking, brought to spectator culmination in his final artwork, Étant donnés.

Duchamp to Katherine Dreier, 5 March 1935, in Affectionately Marcel, 197.

No understanding of Duchamp's monographic project is complete without recourse to Ecke Bonk's exacting and invaluable study. Bonk, The Box in the Valise (London: Thames and Hudson, 1989).

For a discussion of the way this interest traverses Duchamp's entire oeuvre, see Francis Naumann, Marcel Duchamp: The Art of Making Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1999).

In the first monograph on the artist, Duchamp and Robert Lebel list two places and two dates for the Boîte-en-valise: 1938 (Paris) and 1941-42 (New York); cf. Lebel, Sur Marcel Duchamp (Paris: Trianon, 1959), item no. 173. Likewise, in his interview with Pierre Cabanne, Duchamp dates the Boîte-en-valise "from 1938 to '42," Cabanne, Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp, 79. This dating is repeated in the catalogue for Duchamp's first American retrospective in Pasadena in 1963 (entitled "By or of Marcel Duchamp or Rrose Sélavy," like the Duchampian work on which the exhibition was in part modeled), and has become the standard dating in most Duchamp studies since.

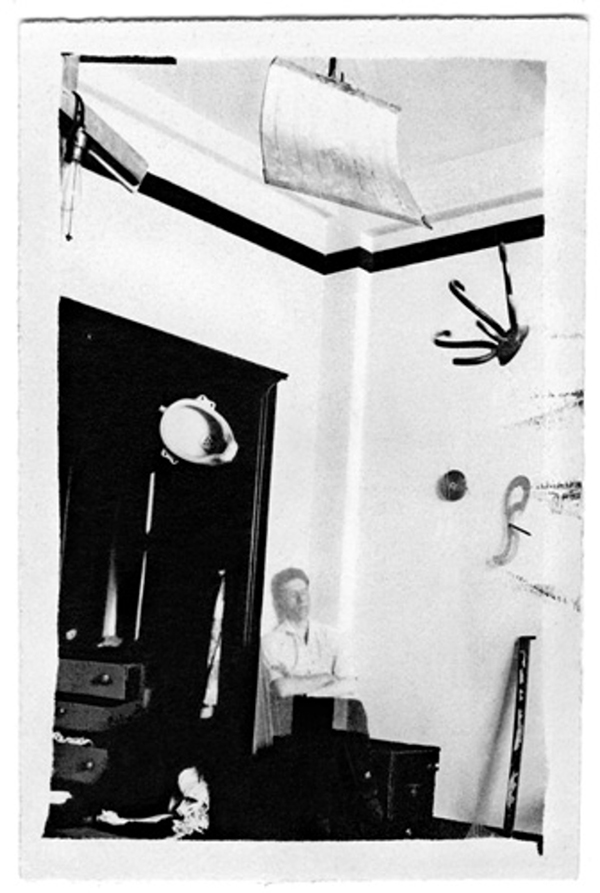

For reproduction in the Boîte-en-valise, Duchamp included Man Ray's photograph of the second store-bought bottle drier (1936), which was subsequently lost, as the first had been (and as was the case with so many of the quotidian objects-cum-readymades). Duchamp did, in fact, have both the famous Steiglitz photograph and the photograph of the urinal dangling from his studio doorframe in his possession during his preparation of the Boîte.

H.P.Roché, from the letters and unpublished documents housed in the Roché archive of the Carlton Lake Collection in the Harry Ransom Research Center at the University of Texas, Austin. Cited in Bonk, Box, 204.

"A Conversation with Marcel Duchamp," filmed interview with James Johnson Sweeney, conducted in the Arensberg rooms at the Philadelphia Museum of Art in 1955. Cited in Dawn Ades, Marcel Duchamp's Travelling Box (London: Arts Council of Great Britain, 1982), 3.

Benjamin Buchloh, "The Museum Fictions of Marcel Broodthaers," in Museums by Artists, ed. A. A. Bronson and Peggy Gale (Toronto: Art Metropole, 1983), 45.

From the notes assembled in À l'infinitif (The White Box), reprinted in Duchamp du signe, ed. Michel Sanouillet and Elmer Peterson (Paris: Flammarion, 1975), 105.

Donald Preziosi discusses the optical impulse of the museum in "Brain of the Earth's Body," in Rhetoric of the Frame: Essays on the Boundaries of the Artwork, ed. Paul Duro (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996), 107.

Krauss, "Im/pulse," 60.

A forthcoming major exhibition, the first ever, about Étant donnés curated by Michael Taylor at the Philadelphia Museum of Art (August-November 2009) promises to reveal hitherto unknown material, studies, and related pieces for an artwork that has, perhaps aptly given its origins, remained shrouded in a certain amount of silence and secrecy since its inauguration.

While I suggest here that the exhibitions should be considered vital sources of influence and preparation for Duchamp's production of things (whether the Boîte-en-valise or Étant donnés), I want to in no way futher art history's too common tendency to privilege object production over ephemeral installations. I don't believe that tangible objects were the endpoint of Duchamp's thinking about the artwork and instead want to insist on his exhibition-making as an artistic practice in itself which, not surprisingly, catalyzed shifts in his thinking about the potential form and meaning of objects, and vice versa.

For a discussion of Duchamp's relationship to the Arensbergs, see Naomi Sawelson-Gorse's "Hollywood Conversations: Duchamp and the Arensbergs," in West Coast Duchamp, ed. Bonnie Clearwater (Miami Beach: Grassfield Press, 1991), 25-45.

The agreement between the Cassandra Foundation and the Museum stipulates that "within or adjoining [the] Museum's collections of works by Marcel Duchamp, in a setting especially designed for the purpose of housing the same... For a period of fifteen years from this date, &leftbracket;the&rightbracket; Museum will not permit any copy of or reproduction of Étant donnés to be made, by photography or otherwise, excepting only pictures of the door behind which said object of art is being installed." See "Agreement between the Cassandra Foundation and the Philadelphia Museum of Art," located at the Philadelphia Museum and reproduced in Mason Klein, The Phenomenology of the Self: Marcel Duchamp's Étant donnés (PhD diss., City University of New York, 1994), appendix.

Duchamp actually composed two instruction manuals, an earlier one that was seemingly a rehearsal or preparation for the later version (which the Philadelphia Museum of Art reproduced in facsimile in 1987). This double, concerted effort is remarkable, suggesting how important it was for Duchamp that the museum understand not only exactly how to reinstall the piece, but also that the museum understand that it was being directed by the artist – so that it is not only the eventual visitor, forced to lean and peep in order to see, but also the museum itself, that must perform as the artist prescripted (Art history will one day come to recognize the manual as an artwork in its own right, in line with Duchamp's various boxes of scribbled notes).

Craig Adcock once said of Étant donnés that it "has no exterior. It has only an interior. from which you look at another interior." Adcock, Definitely Unfinished Marcel Duchamp, ed. Thierry de Duve (Cambridge, MA.: MIT Press, 1991), 342.

André Gervais traces Duchamp's various moves and shifting studio spaces during the construction of the massive installation in his "Détails d'Étant donnés" Les Cahiers du Mnam, n. 75 (spring 2001): 82-97.

The Complete Works of Marcel Duchamp, ed. Arturo Schwarz (New York: H. N. Abrams, 1969).