See the editorial of this issue and, for one example, my “Meshed Space: On Navigating the Virtual,” in Myths of the Marble, exh. cat. eds. Milena Hoegsberg and Alex Klein (Sternberg Press, 2017), 95–112.

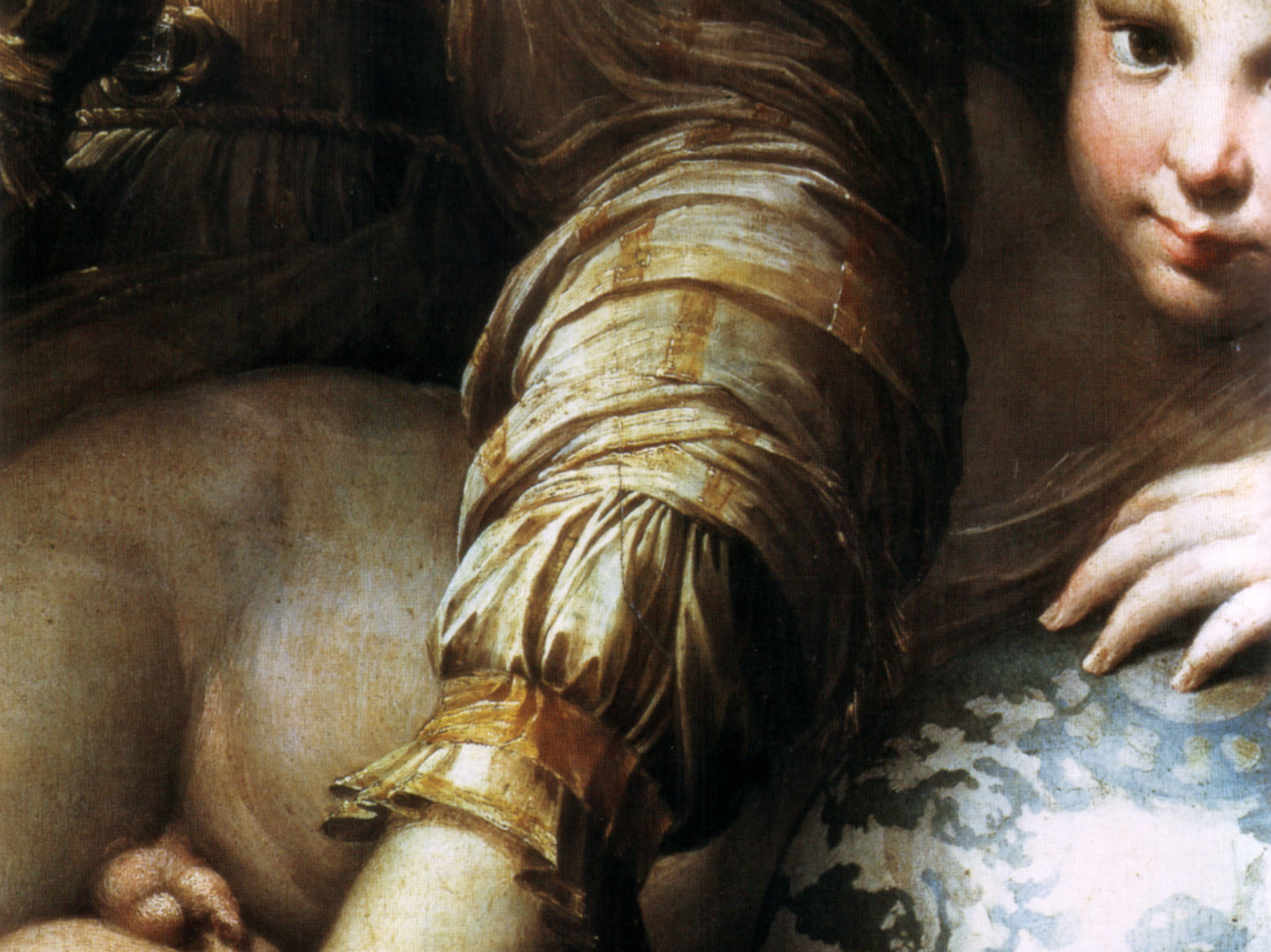

The Madonna of the Rose is a later work by an artist who was called “the little one from Parma” and whose actual name was Girolamo Francesco Maria Mazzola. Parmigianino died young, in 1540, at thirty-seven. But he lived long enough to build a reputation as a pioneer of eccentric Mannerist painting and draftsmanship. Famous for his courtly, flattering portraits of noblewomen and noblemen, but even more so for his anatomically daring figurae serpentinatae in religious paintings such as the notorious 1534/35 Madonna with the Long Neck, Parmigianino was also an accomplished eroticist.

Georges Bataille, “Solar Anus,“ in Visions of Excess: Selected Writings, 1927–1939, ed. and intro. Allan Stoekl, trans. A. Stoekl with Carl R. Lovitt and Donald M. Leslie, Jr. (University of Minnesota, 1985), 7.

See, for example, Eric Robertson, “Volcanoes, Guts and Cosmic Collisions: The Queer Sublime in Frankenstein and Melancholia,” Green Letters, 18, no. 1 (2014): 63–77; Patrick Ffrench, “Bataille’s Nature: On (Not) Having One’s Feet on the Ground,” in Georges Bataille and Contemporary Thought, ed. Will Stronge (Bloomsbury, 2017), 33–49; Nigel Clark and Kathryn Yusoff, “Queer Fire: Ecology, Combustion and Pyrosexual Desire,” Feminist Review 118, no. 1 (2018): 7–24.

See, for example, Leslie Anne Boldt-Irons, “Bataille's ‘The Solar Anus’ or the Parody of Parodies,” Studies in 20th Century Literature 25, no. 2 (2001): 354–74.

Joseph Conrad, Heart of Darkness (1899) (Dover Publications, 1990), 5–6.

Immanuel Kant, “Von dem ersten Grunde des Unterschiedes der Gegenden im Raum” (1763), quoted from Peter Woelert, “Kant’s Hands, Spatial Orientation, and the Copernican Turn,” Continental Philosophy Review 40 (2007): 139–50, 142.

Denise Ferreira da Silva, “1 (life) ÷ 0 (blackness) = ∞ − ∞ or ∞ / ∞: On Matter Beyond the Equation of Value,” e-flux journal 79 (February 2017) →.

See Harun Farocki, “Computer Animation Rules,” lecture IKKM Weimar, July 7, 2014 →.

Which would also mean retelling an epic battle between the “narratologists” and the “ludologists” launched by game scholars Gonzalo Frasca, Jesper Juul, and others. See, e.g., Gonzalo Frasca, “Simulation versus Narrative: Introduction to Ludology,” in The Video Game Theory Reader, eds. Mark J. P. Wolf and Bernard Perron (Routledge 2003), 221–35; Jesper Juul, A Clash between Game and Narrative: A Thesis on Computer Games and Interactive Fiction, 1999 →; Jesper Juul, “Games Telling Stories? A Brief Note on Games and Narratives,” Game Studies 1, no. 1 (July 2001) →.

Kurt Lewin, Principles of Topological Psychology, trans. Fritz and Grace M. Heider (McGraw-Hill, 1936).

See, e.g., Stephan Günzel, “Die Realität des Simulationsbildes: Raum im Computerspiel,” in Die Realität der Imagination: Architektur und das digitale Bild, ed. Jörg H. Gleiter (Bauhaus-Universität, 2008), 127–36 (also →); Steffen P. Walz, Toward a Ludic Architecture: The Space of Play and Games (ETC Press, 2010).

Lewin, Principles of Topological Psychology, 16.

Lewin, Principles of Topological Psychology, 16.

Lewin, Principles of Topological Psychology, 194.

Lewin, Principles of Topological Psychology, 46–47.

See, e.g., David Turnbull, “Maps Narratives and Trails: Performativity, Hodology and Distributed Knowledges in Complex Adaptive Systems—an Approach to Emergent Mapping,” Geographical Research 45, no. 2 (June 2007): 140–49; and Dominic H. ffytche and Marco Catani, “Beyond Localization: From Hodology to Function,” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, no. 360 (2005): 767–79. (No mention of Lewin in either text though.)

Kurt Lewin, “Der Richtungsbegriff in der Psychologie: Der spezielle und allgemeine Hodologische Raum,” Psychologische Forschung 19, no. 3–4 (1934): 249–99, 265.

See, e.g., Katja Rothe, “Mimesis als Sozialtechnik: Kurt Lewin, der Film und die Nachahmung,” Archiv für Mediengeschichte 12 (2012): 127–36.

See Oksana Bulgakowa, “Sergej Eisenstein und die deutschen Psychologen,” in Herausforderung Eisenstein, ed. Oksana Bulgakowa (Akademie der Künste der DDR, 1989), 80–9.

See, e.g., Pia Tikka, Enactive Cinema: Simulatorium Eisensteinens (University of Art and Design Helsinki, 2008), 127–28 →.

I owe the knowledge of this drawing to Elena Vogman and Antonio Somaini.

Antonio Somaini, “Cinema as ‘Dynamic Mummification,’ History as Montage: Eisenstein’s Media Archaeology,” in Sergei M. Eisenstein, Notes for a General History of Cinema, eds. Naum Kleiman and Antonio Somaini, trans. from Russian by Margo Shohl Rosen, Brinton Tench Coxe, and Natalie Ryabchikova (Amsterdam University Press, 2016), 94.

Eisenstein, Notes for a General History of Cinema, 200.

Sergei Eisenstein, “Montage and Architecture” (c. 1938), intro. Yve-Alain Bois, Assemblage 10 (December 1989): 110–31, 116.

Bataille, “Solar Anus,“ 8.

For a Lacanian reading of Bataille’s neologism, see Albert Nguyên, “Bataille ‘Le Jésuve,’” L’en-je lacanien 10 (2008): 47–79.

Arguably anticipating the “labyrinthcity” of a “neo-baroque” present, see Angela Ndalianis, Neo-Baroque Aesthetics and Contemporary Entertainment (MIT Press, 2004).

Gilles Deleuze, Nietzsche and Philosophy (1962), trans. Hugh Tomlinson (Alhlone Press, 1983), 110.

Deleuze, Nietzsche and Philosophy, 110.

Ovid’s Heroides: A New Translation and Critical Essays, eds. Paul Murgatroyd, Bridget Reeves, and Sarah Parker (Routledge, 2017), 119.

For an excellent application of the Ariadne myth to contemporary academia, see Briony Lipton, “Writing through the Labyrinth: Using l’écriture feminine in Leadership Studies,” Leadership 13, no. 1 (2017): 64–80.

The navigational relationship between stellar constellation and orientation (on sea level or on land) in the Mediterranean has been reemphasized recently by artist Bouchra Khalili, in a time when the visual offers of the sky have already been replaced by satellite-based GPS technology. Her 2011 Constellations series of diagrams graph the trajectories of illegalized immigration to Europe while strongly and deliberately resembling astronomical constellations. Khalili’s series is reminiscent of the fact, in Eric de Bruyn’s formulation, “that star patterns have another cultural significance, one that predates their use as a navigational tool: namely, to commemorate the dead.” Eric C. H. de Bruyn, “Beyond the Line, or a Political Geometry of Contemporary Art,” Grey Room 57 (Fall 2014): 24–49, 45.