Before WWII the fascists saw modern art as an ally of communism, communists saw it as an ally of fascism, and the Western democracies saw it as a symbol of personal freedom and artistic realism—as an ally of both fascism and communism. This constellation defined postwar cultural rhetoric. Western art critique saw Soviet art as a version of fascist art, and Soviet critique saw Western modernism as a continuation of fascist art by other means. For both sides, the other was a fascist. And the struggle against this other was a continuation of WWII in the form of a cultural war.

Art institutions, like any small or megalithic enterprise shot through with capital, are inherently political beasts. But the larger of these often try to gloss and shade away certain political lineages or leanings. So, though institutions may develop public strategies offering a new history of modern art that represents the diversity of its protagonists, the vague results are instead an obfuscation of political movements and hidden narratives that would otherwise offer power back to those overlooked and displaced. They continue to be buried deep in the still vast, unseen collection, or, more likely, never collected or touched by the institution in the first place. For example, there is no room in MoMA’s now 708,000 square feet for the major contributions to art made by practitioners of socialist realism. Nor for that matter do we see works even tenuously connected to that tradition—there is no section titled “In and Around Socialism.”

A kind of chain has thus emerged, stretching from Tretyakov to Benjamin to Steyerl. Perhaps we could say that Steyerl, by combining Tretyakov and Benjamin’s ideas in her own way, has restored not so much Tretyakov himself as the Tretyakov who made such a decisive impact on Benjamin’s famous lecture. Theodor Adorno once noted that when Benjamin wrote “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” he had wanted to outdo Brecht. If this is true, then perhaps the person who helped him outdo Brecht was Brecht’s Russian friend Sergei Tretyakov.

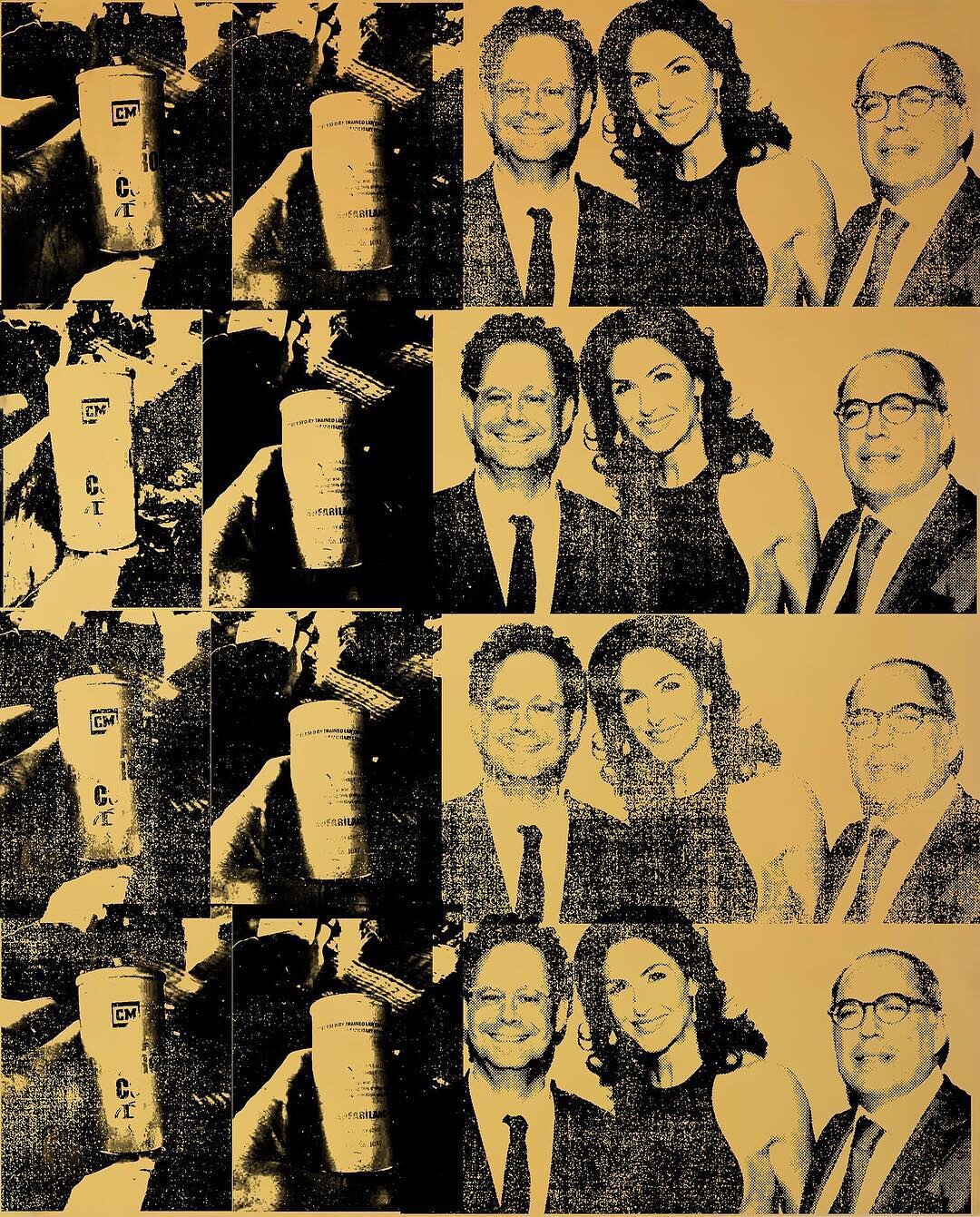

Beyond serving as rich material for social-media posts, the images produced at Selfie Walls also have a more nefarious technological function, which has implications for everything from surveillance to the creation of deep-fake images. The photographers taking photos at Selfie Walls are concentrated on the camera phone, and the camera phone is purely a pretext for the realization of that tool’s possibilities in relation to creating images of the self. The images created at these walls, which are tightly cropped and devoid of context, do not orient people in the world. Instead they erase the world, creating a hybrid space that is part physical and part virtual as it circulates on social media. These images are created in order to orient the subject with their projected self-image, while simultaneously making the projected self-image legible to artificial-intelligence programs.

The recent mass uprisings in Hong Kong; the anti-colonial rage expressed on the streets of San Juan; uprisings in war-torn Iraq; anti-neoliberal revolts in Chile; Central American migrants fleeing agricultural failure and gang violence crossing the US–Mexico border zone—all have been answered with tear gas, an integral component in the liberal-become-authoritarian state’s response to opposition that bypasses conventional routes of negotiation. Its (supposedly) nonlethal crowd control is clearly post-political, maintaining the state’s monopoly on violence. Nonetheless, these worldwide revolutions rise up against everything tear gas represents, and it is these struggles that can offer important lessons for the politics of climate emergency, beginning with a necessary expansion of our terminology.

True, artists too less and less resemble industrial workers, and more and more resemble managers. But they are still heroic, highly individualized managers nonetheless—that is, the successful ones (the lesser figures are now relegated largely to the artistic equivalent of care work). And it’s telling that, whatever else may change, and however much the Romantic conception of the artist now seems to us trite, silly, and long-since-abandoned; however much discussion for that matter there is about artistic collectives; at a show like the Venice Biennale, or a museum of contemporary art, almost everything is still treated as if it springs from the brain of a specific named individual.

Imagine experts in the world of art admitting that the entire project of artistic salvation to which they pledged allegiance is insane and that it could not have existed without exercising various forms of violence, attributing spectacular prices to pieces that should not have been acquired in the first place. Imagine that all those experts recognize that the knowledge and skills to create objects the museum violently rendered rare and valuable are not extinct. For these objects to preserve their market value, those people who inherited the knowledge and skills to continue to create them had to be denied the time and conditions to engage in building their world. Imagine museum directors and chief curators taken by a belated awakening—similar to the one that is sometimes experienced by soldiers—on the meaning of the violence they exercise under the guise of the benign and admitting the extent to which their profession is constitutive of differential violence.

Why should we talk about absurdism today? The citation about Daniil Kharms falling asleep a citizen of St. Petersburg and waking up a citizen of Petrograd, then Leningrad the next day, provides one reason. For readers today, a story like this may bring to mind Brexit, a lived reality in which we do not know which geopolitical constellation we will be waking up in tomorrow, and in which the epistemic indeterminacy of its day-to-day reality is itself an instrument of power. Absurdism was an art form that emerged in the context of a similarly explicit sense of political uncertainty. And yet, absurdism is not parody. Indeed, absurdism is not a category that itself belongs to the absurd.

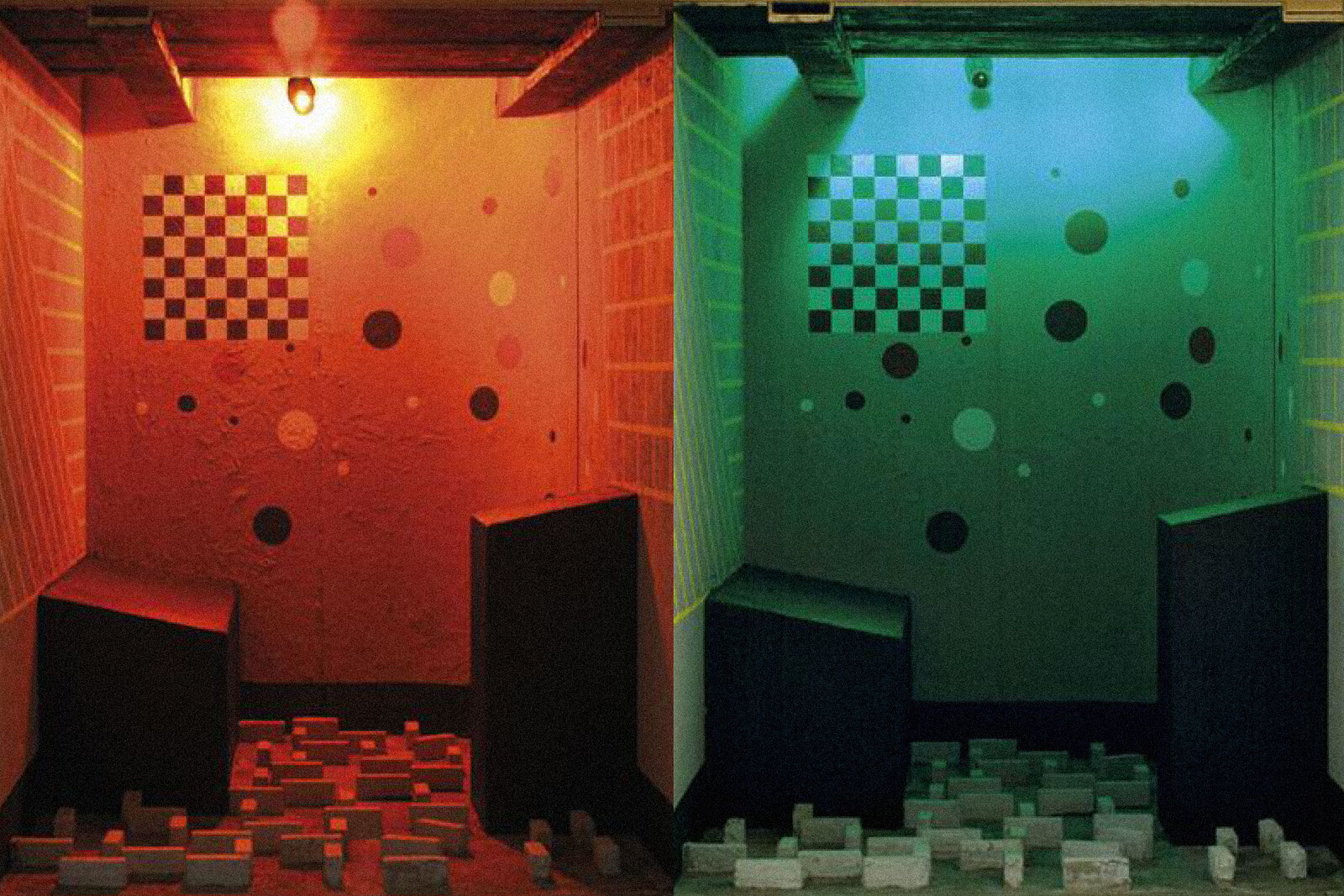

She couldn’t move, and this quickly distorted every perspective, collapsing the vanishing points. She transmitted her instability to the surroundings, a fluctuation that made it impossible for her to grab on to something. To grab on to anything. All her memories had dissolved into that uncontrollable fluctuation. This was why she took Remembrant, so she could see them scroll by as though on a roll of celluloid. She knew they were hers, those memories, but she didn’t recognize them. Her memories from ten years earlier when she threw her arms around her mother’s neck, and her memories from two nights ago—which she felt in her muscles and tendons, but didn’t recognize—when she had come across the two old corpses, like buoys tossed around by a stormy sea, by a storm which had its origin in herself. She had bludgeoned them repeatedly in order to finally attain a bit of calm.

_02.jpg,1600)