This conclusion is largely grounded in the seminal work of historian Aleksandr Pyzhikov. See his Facets of the Russian Schism: The Secret Role of Old Rite from the Seventeenth Century to 1917 (in Russian) (Kontseptual, 2018).

A. Haxthausen, Studien über die innern Zustände, das Volksleben und insbesondere die ländlichen Einrichtungen Russlands. Translated into English as The Russian Empire: Its People, Institutions and Resources (Chapman & Hall, 1856), 277.

A. L. Shchapov, The Schism of the Russian Old Rite, Considered in Connection with the Internal State of the Russian Church and Civil Society in the Seventeenth and Early Eighteenth Century (1859). Cited in Pyzhukov, Facets of the Russian Schism, 31.

For more information see Aleksandr Etkind, Khlyst: Sects, Literature, and Revolution (in Russian) (NLO 1998).

Charles Taylor, A Secular Age (Belknap Press, 2007), 300.

Orlando Figes, A People’s Tragedy (Viking, 1997), 98–101, 518–19.

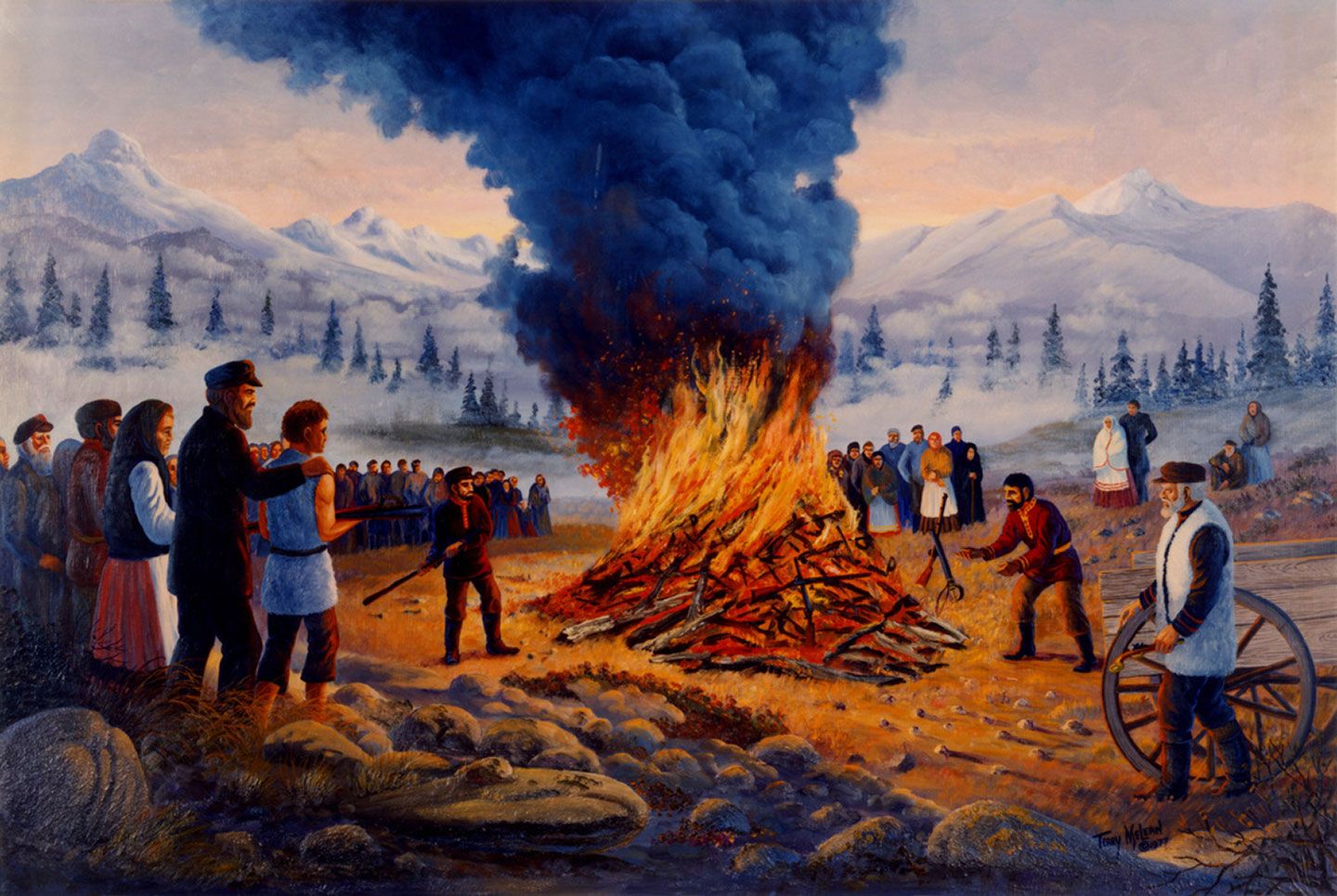

Taylor, A Secular Age, 259. The “Pugachovschina” was a peasant uprising, led by Yemelian Pugachev, 1773–75. The insurrection united Cossacks, peasants, and various ethnic populations in Russia against autocracy. Most of the several hundred thousand rebels came from the Raskol.

A. I. Klibanov, History of Religious Sectarianism in 1860s Russia (in Russian) (Nauka, 1917); Kirill Chistov, Russian Popular Socio-Utopian Legends, Seventeenth to Eighteenth Century (in Russian) (1967).

V. I. Lenin, Complete Works, vol. 4, 228 (in Russian), as cited in Klibanov, History of Religious Sectarianism, 4.

Aleksandr Pyzhikov, Roots of Stalinist Bolshevism (in Russian) (Argumenty Nedeli, 2018), 530–31.

Aleksandr Agurskiy, The Ideology of National-Bolshevism (in Russian) (YMCA-Press, 1980), 322.

Taylor, A Secular Age, 299.

An informal literary and occultist club, which met at the apartment of writer Yuri Mamleev on Yuzhinsky Street. After Mamleev’s expulsion from the USSR, the group continued its existence into the 1990s. Other prominent members included Evgeniy Golovin, Aleksandr Dugin, Geydar Dzhemal, and Igor Dudinskiy.

In The New Age of Russia: Occult and Esoteric Dimensions, eds. Birgit Menzel, Michael Hagemeister, and Bernice Glatzer Rosenthal (Verlag Otto Sagner, 2012).

Translated into English as Mikhail Epstein, Cries in the New Wilderness: From the Files of the Moscow Institute of Atheism, trans. Eve Adler (Paul Dry Books, 2002), 236.

For Epstein’s introduction in the original Russian, see →.

Birgit Menzel, “The Occult Revival in Russia Today and Its Impact on Literature,” The Harriman Review 16, no. 1 (Spring 2007): 1–14.

Anatoliy Moskvin, “Cross without a Victim,” afterward to Thomas Wilson, The Swastika, tr. Anatoliy Moskvin (in Russian) (Knigi, 2008), 360, 362.

This sense of the word “prison,” initially applied to Russia by Marquis de Custine in the middle of nineteenth century, was later picked up by Russian progressive circles. In 1914 the term was transformed and popularized by Lenin as “the prison of the nations,” aiming to characterize Russian national policy at the time. In the Soviet period it became a kind of cliché referring to tsarist Russia.

Chris Dumas, “Horror and Psychoanalysis. An Introductory Primer,” in A Companion to the Horror Film, ed. Harry M. Benshoff (Wiley-Blackwell, 2014), 21–37.

Mikhail Epstein, Religion after Atheism: New Possibilities of Theology (in Russian) (ACT-Press, 2013).

Epstein, Religion after Atheism, 19.

Taylor, A Secular Age, 515.

Translated from the Russian by Sergey Levchin.