A significant location as it was the site of a famous massacre by the British in 1906, which was one of the main factors in prompting the strong national resistance movement, of which Kamil was a major figure.

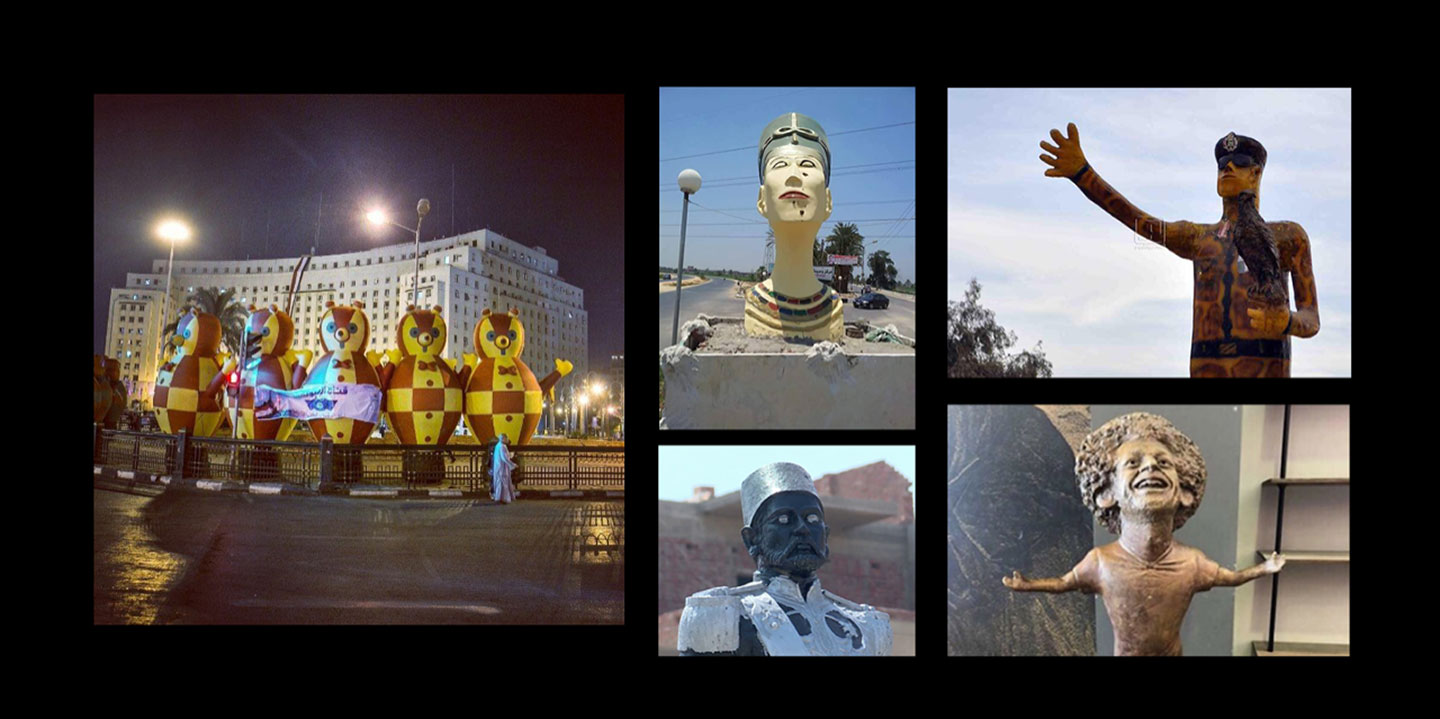

I have been able to locate at least fifteen such statues, including renovations that render the original unrecognizable. Examples include the 2015 mermaid in a public square in the city of Safaga located in the Red Sea governorate, the 2016 lions placed in the entrance of the Teacher’s Syndicate in Cairo, the 2017 lion in Tanta, the 2018 statue of the famous Egyptian soccer player Mohamed Salah by the artist Mai Abdallah, which was unveiled at the inauguration of the World Youth Forum in Sharm el Sheikh, the 2017 renovation of the Khedive Ismail statue in the town of Ismailia, the 2016 renovation of the statue of the famous Egyptian singer and composer Mohamed Abdel Wahab in Cairo, the 2015 renovation of the statue of the writer and thinker Abbas Mahmoud al-Aqqad in Aswan, the 2015 renovation of the statue of the scholar and thinker Rifa’a al-Tahtawi located in Thata, the 2016 renovation of the statue of the revolutionary figure Ahmed Urabi located in the town of Zaqaziq, where he was born, and the 2016 renovation of the statue of the famous singer Om Khalthoum in the neighborhood of Zamalek in Cairo where she lived, among others.

Alexandra Hutzler, “Donald Trump Admits He Only Tells the Truth ‘When I Can,’” Newsweek, November 1, 2018 →.

Prior regimes may have come close to creating caricatures of the institutions they occupy as well, including the Mubarak regime in Egypt and George Bush Jr. in the US, or to go back even further, Ronald Reagan, but this moment seems to offer a new benchmark.

It is hard to distinguish Trump proper from his impersonator on Saturday Night Live, which has more to do with Trump’s performance than his impersonator’s skills.

Alenka Zupančič, The Odd One In: On Comedy (MIT Press, 2008), 55.

Zupančič, The Odd One In, 210.

Zupančič, The Odd One In, 210.

Zupančič, The Odd One In, 185.

Zupančič, The Odd One In, 15.

Zupančič, The Odd One In, 15.

Zupančič, The Odd One In, 15.

Jalal Toufic, Forthcoming (Sternberg Press, 2014), 44.