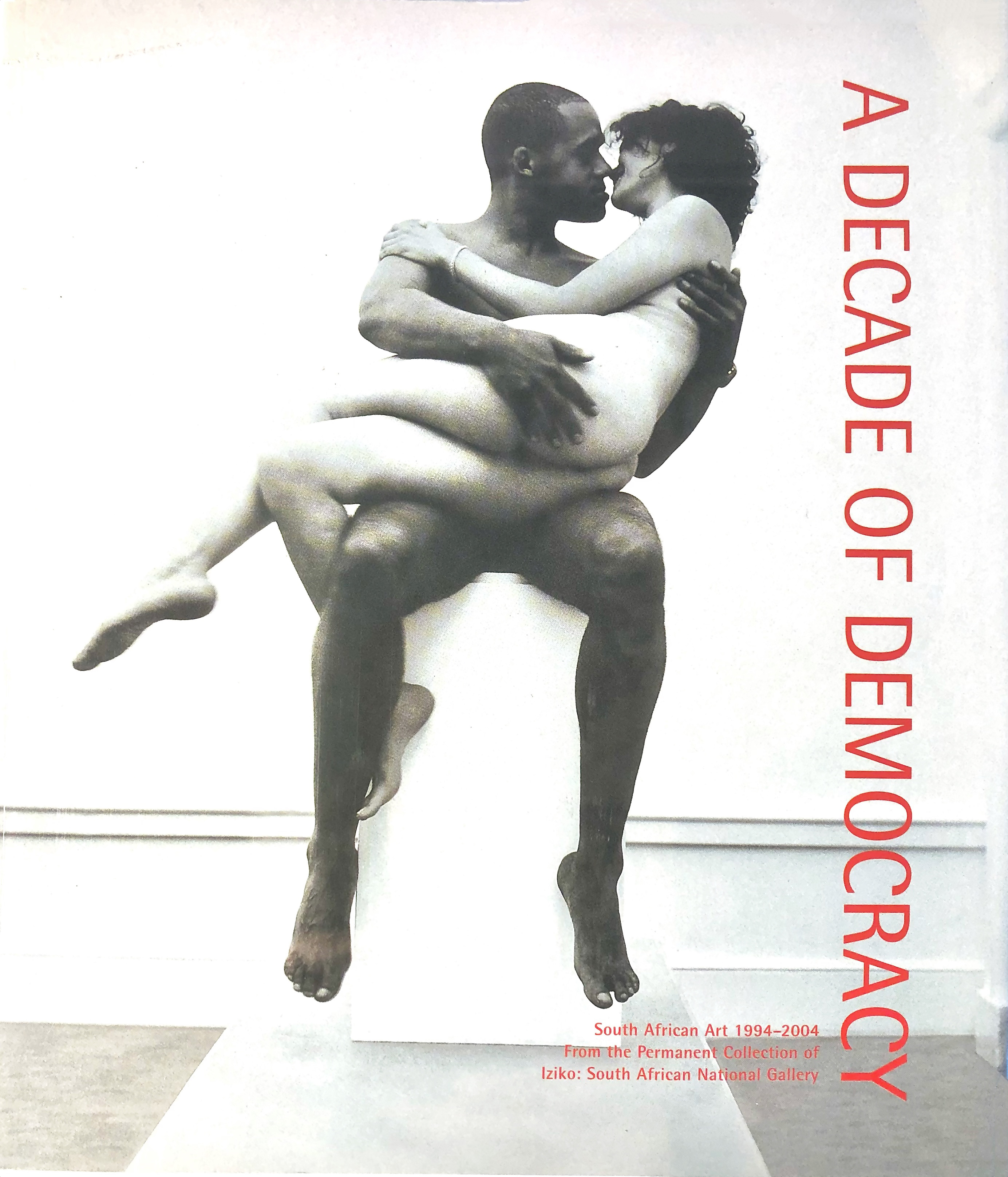

Ashraf Jamal, “The Bearable Lightness of Tracey Rose’s The Kiss,” in A Decade of Democracy: South African Art 1994–2004: From the Permanent Collection of Iziko: South African National Gallery, ed. Emma Bedford (Double Storey Books, 2005), 102–9. The essay focuses on Tracey Rose’s video works TKO (2000) and Ciao Bella (2001), and her photographic print The Kiss (2001).

The theory has taken further shape in Jamal’s writings in art magazines, as well as in the introduction to his book In the World: Essays on Contemporary South African Art (Skira, 2017), 11–14.

Kwame Anthony Appiah, “Is the Post- in Postmodernism the Post- in Postcolonial?” Critical Inquiry 17, no. 2 (1991); Homi Bhabha, “Beyond the Pale: Art in the Age of Multicultural Translation,” in Cultural Diversity in the Arts: Art, Art Policies and the Facelift of Europe, ed. Ria Lavrijsen (Royal Tropical Institute, 1993); Valentin Yves Mudimbe, The Idea of Africa (Indiana University Press, 1994).

J. M. Coetzee, “Jerusalem Prize Acceptance Speech (1987),” in Doubling the Point: Essays and Interviews, ed. David Attwell (Harvard University Press, 1992), 96–101.

Coetzee, “Jerusalem Prize.”

“How we long to quit a world of pathological attachments, and abstract forces of anger and violence, and take up residence in a world where a living play of feelings and ideas is possible, a world where we truly have an occupation.” Coetzee, “Jerusalem Prize,” 98.

Coetzee, “Jerusalem Prize,” 96.

Coetzee, “Jerusalem Prize,” 96.

“The unfreedom of the master-caste.” Coetzee, “Jerusalem Prize,” 96.

“The crudity of life in South Africa, the naked force of its appeals, not only at the physical level but at the moral level too, its callousness and its brutalities, its hungers and its rages, its greed and its lies, make it as irresistible as it is unlovable.” Coetzee, “Jerusalem Prize,” 99. Italics added.

“South Africa is not irresistible and unlovable as Coetzee has claimed, a claim as efficacious as it is disingenuous; rather, the view I would propose is that South Africa is resistible and lovable. By this I mean that one survives the barbarism of one’s history irrespective of the template that has normalised one’s illness. Coetzee knows this, as does any thinker who has delved into the pain that has been said to define what it means to be South Africa.” Jamal, “Bearable Lightness,” 106.

Gayatri Spivak, “When Law is Not Justice,” New York Times, July 13, 2016.

Jamal, “Bearable Lightness,” 108.

Jamal, “Bearable Lightness,” 106.

Jamal, “Bearable Lightness,” 106.

Gabriela Basterra, The Subject of Freedom: Kant, Lévinas (Fordham University Press, 2015), 9.

Jamal, “Bearable Lightness,” 106.

Basterra, The Subject of Freedom, 6.

Basterra, The Subject of Freedom, 6.

Coetzee, “Jerusalem Prize,” 97.

Basterra, The Subject of Freedom, 7.

Coetzee, “Jerusalem Prize,” 98.

Coetzee, “Jerusalem Prize,” 98.

Quoted in Steven Groarke, “The Disgraced Life in J. M. Coetzee’s Dusklands,” American Imago 75, no. 1 (2018).

Groarke, “The Disgraced Life,” 35.

Jamal, “Bearable Lightness,” 103.

Ben Okri, Thirteenth Steve Biko Annual Memorial Lecture, University of Cape Town, September 12, 2012 →.

Milan Kundera, “The Art of Fiction,” Paris Review, no. 92 (Summer 1984).

“The evasion of the political could, I believe, jeopardize the hard-won conquests of the democratic revolution, which is why, in the essays included in this volume, I take issue with the conception of politics that informs a great deal of democratic thinking today. This conception can be characterized as rationalist, universalist and individualist. I argue that its main shortcoming is that it cannot but remain blind to the specificity of the political in its dimension of conflict/decision, and that it cannot perceive the constitutive role of antagonism in social life.” Chantal Mouffe, introduction to The Return of the Political (Verso, 1993), 2.

Mouffe, The Return of the Political, 4.

Hannah Arendt, On Violence (Harcourt Brace, 1970), 69.

Arendt, On Violence, 75.

Emma Bedford, introduction to fresh: Tracey Rose (Iziko: South Africa National Gallery, 2003), 5.

Kim Gurney, “Ten Years On,” Arthrob, no. 1 (May 2004).

Kellie Jones, “Tracey Rose: Post-apartheid Playground,” in fresh: Tracey Rose.