S. N., “Pasolini in Beirut: More Important than Realizing the Work Is Dreaming It,” Annahar Newspaper (Beirut), May 4, 1974.

Ed Vulliamy, “Who Really Killed Pier Paolo Pasolini?” The Guardian, August 23, 2014 →.

Nick Denes writing on Raoul-Jean Moulin, quoted in Anthony Downey, “Contingency, Dissonance and Performativity: Critical Archives and Knowledge Production in Contemporary Art,” in Dissonant Archives: Contemporary Visual Culture and Contested Narratives in the Middle East, ed. Anthony Downey (IBTauris, 2015), 30.

Audre Lorde, Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches (Crossing Press, 1984), 53.

Lorde, Sister Outsider, 54, 55.

Letter from Samia Tutunji to Pier Paolo Pasolini, January 5, 1973, IT ACGV PPP.I.1179. 1, Archivio Contemporaneo Bonsanti, Florence, Italy. Unless noted otherwise, all excerpts from the archival documents and articles have been translated from Arabic, French, and Italian by me.

To this day, Lebanese filmmakers and distributors continue to fight against censorship of films imposed by religious and political interests and enforced by Lebanese security officials.

The invitation came from the Mouvement Social, a social and political organization founded by a priest and still active to this day. Letter from Robert Misk from the Mouvement Social to Pier Paolo Pasolini, February 19, 1970, IT ACGV PPP.I.1213. 2(a-c)/b, Archivio Contemporaneo Bonsanti.

Letter from the Italian Cultural Institute in Beirut to Pier Paolo Pasolini, February 24, 1970, IT ACGV PPP.I.1213. 2(a-c)/c, Archivio Contemporaneo Bonsanti.

Manuscript for an article entitled “Mostri e mostriciattoli. Beyruth. Mercks. I donatori di sangue,” May 1, 1969, IT ACGV PPP.II.1.145. 37, Archivio Contemporaneo Bonsanti. The archive mentions that the article was published in Tempo 31, no. 19 (May 10, 1969) with a slightly different title: “Mostri e mostriciattoli. I pasticcini di Beirut. La faccia di Merckx. Donatori di sangue.”

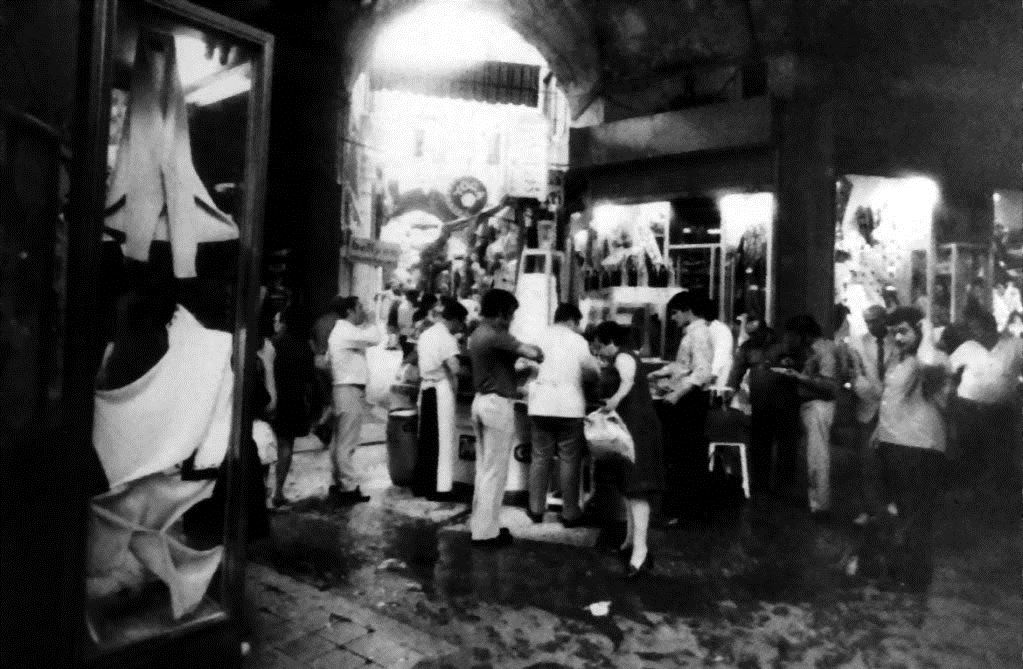

The souks of downtown Beirut, the popular heart of the city, were destroyed during the civil war. In the 1990s, they were privatized and rebuilt with fancy stores selling expensive international brands.

Télé Liban became Lebanon’s first public television network in 1959.

Janine Rubeiz et Dar el Fan: Regard vers un patrimoine culturel (Beirut: Dar Annahar Press, 2003), 23.

Janine Rubeiz et Dar el Fan, 29. Founded in 1967 by Janine Rubeiz, an “enlightened” bourgeois socialite, the center programmed, over a period of eight years, 240 conferences and debates, sixty poetry nights, ninety exhibitions, and 150 film screenings from different parts of the world. A 1972 manifesto makes clear the humanistic approach of Dar el Fan, describing its mission as “political engagement” with historical events considered as lived experiences that recognize “the suffering, the expectation, and the hope” of the Other.

Original brochure of the Ciné-Club of Beirut, May 3, 1974, IT ACGV PPP.V.3.213. 70, Archivio Contemporaneo Bonsanti.

Simone Fattal, email to the author, September 27, 2020.

The reference is from Pasolini’s poem “The Ashes of Gramsci,” in Pier Paolo Pasolini, Pier Paolo Pasolini: Poems, trans. Norman MacAfee (Noonday Press, 1996), 23. In 1949, Pasolini fled his native Friuli with his mother and settled in Rome after being accused of “obscene acts” with minors in public. Even though he was acquitted, he lost his job as a teacher and was removed from the Communist Party (see Ian Thomson, “Pier Paolo Pasolini: No Saint,” The Guardian, February 22, 2013 →.) It was in the borgate that he found his first cinematic inspirations crystalized in Accatone (1961) and Mamma Roma (1962). There, he also discovered the ragazzi and a violent homosexual world that would bring him both “fortune and fate.” This is according to his friend and renowned Italian writer Alberto Moravia, interviewed after Pasolini’s assassination in Those Who Tell the Truth Shall Die, a 1981 documentary by Philo Bregstein.

Pier Paolo Pasolini: Poems, 21.

Pier Paolo Pasolini: Poems, 9.

S. N., “Pasolini à Beyrouth: “Rêver c’est une forme de religiosité,” L’Orient le Jour (Beirut), May 5, 1974.

S. N., “Pasolini in Beirut: More Important than Realizing the Work Is Dreaming It.”

Emily K. Hobson, Lavender and Red: Liberation and Solidarity in the Gay and Lesbian Left (University of California Press, 2016).

Todd Shepard, Sex, France, and Arab Men, 1962–1979 (University of Chicago Press, 2017).

Jarrod Hayes, “Queer Resistance to (Neo-)colonialism in Algeria,” in Postcolonial, Queer: Theoretical Intersections, ed. John C. Hawley and Dennis Altman (SUNY Press, 2001).

Joseph Massad, Desiring Arabs (University of Chicago Press, 2007), 162.

Ghassan Makarem, “The Story of HELEM,” Journal of Middle East Women’s Studies 7, no. 3 (2011): 98, 102.

José Esteban Muñoz, Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity (NYU Press, 2009), 1.

Inspired by the call for “a third-world gay revolution” (a term used to include Black people, Latin Americans, and all other peoples of color) that appeared in a gay publication in New York in the early 1970s. “T.W.G.R.: Third World Gay Revolution,” Come Out! A Liberation Forum for the Gay Community 1, no. 5 (September–October 1970), 12.

A statement that Pasolini made in an interview published by the French newspaper Le Monde on February 26, 1971 as mentioned in Enzo Siciliano, foreword to Pier Paolo Pasolini: Poems, xiv.

Porno-Teo-Kolossal is a film that Pasolini wrote but never realized. Information from the script is based on Julie Paquette, “From Capitalist Development to the Endless Sequence Shot: The Four ‘Utopias’ of Porno-Teo-Kolossal,” Cinémas 27, no. 1 (2016): 99. Paquette’s essay provides extensive details of the script, including the following excerpt (in French): “Non seulement des minorités hétérosexuelles, mais aussi des minorités noires, des minorités juives, des minorités tzigane, qui vivent ici dans la liberté la plus absolue, y compris intérieure … Sodome, … tout est fondé sur un sens réel de la démocratie.”

Ara H. Merjian, Against the Avant-Garde: Pier Paolo Pasolini, Contemporary Art, and Neocapitalism (University of Chicago Press, 2020), 214–15.

Patrick Allen Rumble, Allegories of Contamination: Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Trilogy of Life (University of Toronto Press, 1996), 135, 140.

Daniel Humphrey, Archaic Modernism: Queer Poetics in the Cinema of Pier Paolo Pasolini (Wayne State University Press, 2020), 108.

Humphrey, Archaic Modernism, 108.

Luca Caminati, “Notes for a Revolution: Pasolini’s Postcolonial Essay Films,” in The Essay Film: Dialogue, Politics, Utopia, ed. Elizabeth A. Papazian and Caroline Eades (Columbia University Press/Wallflower, 2016), 131.

Caminati, “Notes for a Revolution,” 133.

Paquette, “From Capitalist Development,” 107.

Paquette, “From Capitalist Development,” 106.

Paquette, “From Capitalist Development,” 106.

Paquette, “From Capitalist Development,” 111.

The last lines of “The Ashes of Gramsci,” in Pier Paolo Pasolini: Poems, 23.

Reference from a posthumous Pasolini manuscript mentioned in Pier Paolo Pasolini: Poems, xi. The second reference is from Walter Benjamin’s 1940 essay Theses on the Philosophy of History.

See Rasha Younes, “‘If Not Now, When?’ Queer and Trans People Reclaim Their Power in Lebanon’s Revolution,” Human Rights Watch, May 7, 2020 →.