There is something now, in reading my childish linguistic knitting together of the attempt to conceive narcotic states, that evokes the adolescent sensation of reading the opening monologue of William Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury. The novel features Benjy, once Maury, a boy who operates in another register than the normative. His name is changed by his mother when it becomes clear that he communicates outside of the pale. I recall, too, while reading, the feeling that I was at the edges of comprehending Benjy’s metabolization of place. White and wealthy Benjy is no lumpen; but he is a portal into a furtive space where a stubborn growth of language only hedges at an experience that is marginal and unmanageable. At sixteen, I mistook my attachment as something regional and racialized—that we, Benjy, me, my aunts, my mother, were sutured together by white rot alone; we were something spoiled in the hot, wet shade, but still alive (swelling) and vocal (crooning, babbling, screaming). In 1910, in 1923, in 1954, my family, lapsed southern Baptists and excommunicated Mormons, were dirt poor cotton sharecroppers. I welcomed Benjy into my familial swill because he was outcast by the plantation elite. At this juncture in time, I think the organizing margin is class—a deep, lovely, fetid alliance with those of us from another zone, not necessarily southern and not necessarily white, that repulses the supposed rewards of good behavior. Adieu, Maury?

Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, Manifesto of the Communist Party, trans. Samuel Moore, English edition of 1888.

Djemila Zenaidi and Jérôme Beauchez, “Sur La Zone: A Critical Sociology of the Parisian Dangerous Classes (1871–1973),” Critical Sociology (2019): 1–18.

At a certain juncture, between 1840 and 1930, approximately 75 percent of the population of Quebec temporarily migrated to New England, transitioning from an agricultural work force to an industrial one. Half returned. Looking at the obituaries of workers-who-stayed in the local Winchendon Courier, one notes an emphasis on language acquisition and the melting of the French patronymics into something that is not formally French or English. One obituary of a Quebec orphan carefully notes: “She taught herself to read, write, and speak in English.” This is very far away from the long-ago peasants of Languedoc, signing a legal document by scrawling a quick sketch of a tool to stand in for their signature. The end of the peasant?

An incorrect spelling of a child’s name is probably not enough to elude authorities looking to crack down on labor infractions. However, Hine’s documentation of underage workers in Lawrence, MA frequently misses names and misnames others. Some of this can be attributed to a rapid conversation between photographer and worker, to workers’ subterfuge, to children taking the piss out of a stranger with strange requests, but also to the way in which sharing official identification papers was common practice in immigrant communities at that time.

I lived near the remains of the Lowell mills. At the national historic site, attendants—sometimes former workers—will gun up a fraction of the looms and it is deafening. Everything vibrates. Me and my baby wore noise-reducing headphones and still the din leaked in. A text-based display panel described widespread hearing loss amongst long-term workers. I begin to wonder how language acquisition and emotional cultures were shaped by temporary deafness on the job and long-term hearing loss after the job. There is a New England stereotype of the stoic, silent working-class grandparent that might need to be revisited in light of the impact of industrial worksites →.

This information comes from a private local history social media group. A senior user described how his aunt was a member of the KKK’s ladies division in Winchendon and how she had asked his mother to send red stones for these crosses. He also described another aunt, perhaps from the other side of the family, who was Catholic and was forced by the KKK to abandon her home in Florida, Massachusetts.

See →.

See →.

Before this castle was for rent, the owners used to throw an annual Bastille Day Party on the shores of their beach. There was a picnic and professional fireworks. Not unlike the way the various global iterations of gilets jaunes (née yellow vests) rotate from far left to far right, restitched into near wrong … it was unclear as to whether the picnic was commemorating the end of kings or mocking the revolutionary mob who stormed the prison. CACA- PEE-PEE- CAPITALIST! CACA- PEE-PEE! CACA! CAW CAW CAW!

After publication, I pulled up an email from 2016. It was written to a woman who, like me, had fled the area. If one goes by Linked In, my route was more rough-hewn than her ivy-league escape chute. When I was fourteen, we went to a Cure show in Worcester together but we have not spoken since 1991. I can still summon the smell of her laundry just out of the dryer. In the email, I wrote about my interaction with the only other person I have met from Winchendon since leaving the area and I see that my reconstruction was in error. There is more. Here is I am referring to meeting the hometown filmmaker at MOMA: “I don't recall their name. They said they were shocked when they found out the Fred Sandback museum was in Winchendon and felt a sort of class melancholy- a sense of being robbed of the possibility of contact with these works as a working class kid in Winchendon that was strange and needed other strange things.” A sort of class melancholy. The town was mossy with that. a sense of being robbed of the possibility of contact with these works as a working class kid in Winchendon. The filmmaker pinpoints that there is no Robin Hood situation in this place. They can't break in (very high windows) and feel. It is an old bank. When I went on my tour of Charters Implants/ Fred Sandbook Museum he said the old safe was stuffed with Museum ephemera that never got handed out. Sandback said himself, “My work is ‘about’ any number of things, but ‘being in a place’ would be right up there on the list.” This is a pull quote from the David Zwirner website press materials accompanying the Fred Sandback show that opened on April 1, 2022.

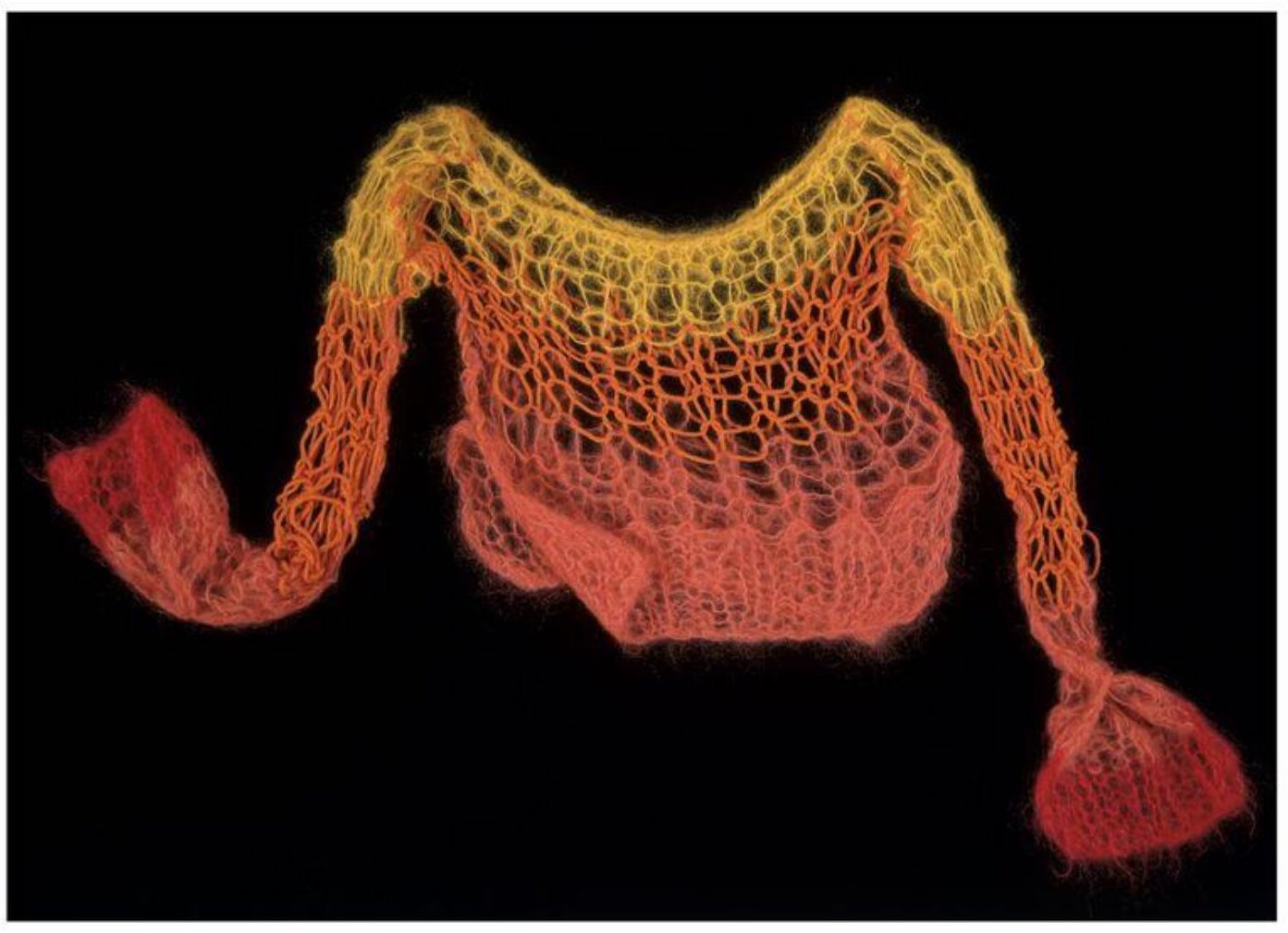

Smithsonian Collection.