Just weeks before the election, Hard Line managed to receive triple the media exposure compared to the two prime minister candidates. Although the party’s alleged mission to enter parliament failed (by only 0.2 percent of the vote), Hard Line clearly won in the eyes of the generalized attention economy. The party garnered millions of YouTube and Snapchat views—the latter among children and teens especially—and graced the headlines of the largest Danish newspapers, in which Paludan became the third-most-mentioned politician during the campaign.

To promote an anti-trans agenda, Ibi-Pippi has exploited a law concerning legal gender change to conduct various purposefully triggering actions, such as attempting to access a female changing room and a swimming class for Muslim women. Previously, Ibi-Pippi also walked in a “hetero pride” parade, penetrated a Putin blow-up doll, and carried out a public performance that allegedly involved blending and drinking a fetus.

While most critics believed that Ibi-Pippi’s vandalism was an act of spontaneous idiocy, a quick dive into Facebook reveals that this idea of making an “homage” to The Disquieting Duckling had actually been brewing for five years, as depicted in a painting including pedophilic imagery →. Ibi-Pippi also claimed to be in spiritual contact with Jorn beforehand → (watch 03:00). This does not take away from the stupidity of the action as much as it underlines the persistent veneration that a new generation of far-right artists seems to hold for Jorn. This problematizes the analyses that have framed the incident at Museum Jorn as some sort of “right-extremist” attack on a “left-wing artwork.” See, for example, Lukas Slothuus, “Why Is the Danish Far Right Vandalizing Left-Wing Artwork?” Jacobin, April 5, 2022 →.

In 2016 Jensen attempted a similar performance in the Kunsten art museum in northern Denmark but ended up violently assaulting two employees. Jensen was sentenced for the assault. More recently, Jensen gave the opening performance for a far-right exhibition in Warsaw, where he yelled the n-word, waved the Confederate flag, and reenacted the murder of George Floyd in blackface.

For another example of the legacies of fascist-leaning “provo art,” see Sven Lütticken, “Who Makes the Nazis?” e-flux journal no. 76 (October 2016) →. —Eds.

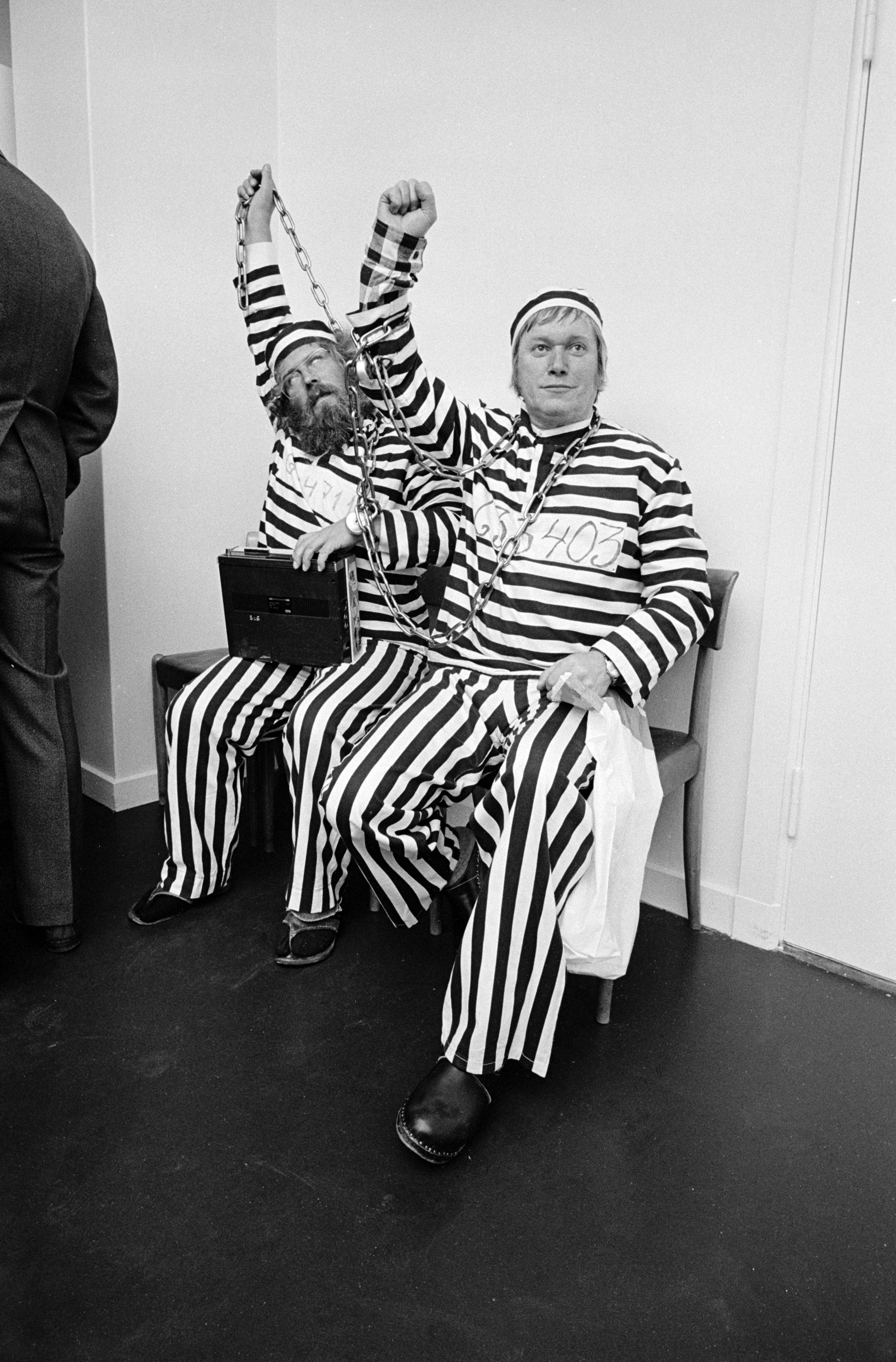

In a Danish political context, an obvious predecessor for this “Faustian pact” between a provo artist and a far-right lawyer can be identified from 1970–73. Back then, the Situationist provo Jens Jørgen Thorsen hired the charismatic libertarian provo Mogens Glistrup as his defense lawyer. In 1973, Glistrup entered the Danish parliament with the populist-libertarian Fremskridtspartiet, a party acclaimed and affronted for its heroization of tax cheaters and anti-Muslim politics. Thorsen’s connection to the far-right was further bolstered in the late 1970s and ’80s when he toured around Denmark with a central member of Fremskridtspartiet, Kristen Poulsgaard, in the aftermath of the anti-intellectual movement “Rindalism.”

For an in-depth account of the exclusion and subsequent emergence of the Scandinavian Situationists, see Howard Slater, “Divided We Stand: An Outline of Scandinavian Situationism,” Infopool, no. 4, 2001 →. Notwithstanding the virtues of Slater’s text, it suffers from a complete lack of attention to the Nashists’ more diabolical side. It shares this with later discussions by Jakob Jakobsen, Mikkel Bolt Rasmussen, and others.

J. V. Martin, “Définition,” Internationale Situationniste, no. 8 (January 1963): 26; appeared in Danish in Situationistisk Revolution, no. 3 (1970): 44.

Martin, “Définition” (emphasis ours). This conceptual trajectory seems all the more ironic given the anti-fascist origin of its very name. Born as Axel Jørgensen, “Jørgen Nash” was—according to biographer Lars Morell—originally a cover name taken up by a young, up-and-coming poet who was sent to Nazi Germany by the Danish resistance movement as a specialist worker in aviation. In 1941, “Nash” was caught by the Gestapo and detained in Berlin for two months. As such, Nashism is already a cruel détournement of an explicitly anti-Nazi pseudonym.

With the notion of “compact spectacle,” we borrow the epistemological standpoint of Debordian diagnostics. For Debord, the society of the spectacle is conceived as a fetus whose evolutionary-cumulative stages morph from the bureaucracies of totalitarian states (concentrated spectacle) to the great commodity boom of the postwar Keynesian compromise (diffuse spectacle) and ultimately to the synthesis of a neoliberal, biopolitical totality (integrated spectacle). If, in other words, we think of Debord as a driver on the catastrophic highway of Western modernity, “our” contemporary moment seems to induce the feeling of living amid a universal traffic jam caused by a crash between a few unmanned monster trucks and a gang of street vendors.

In his memoir The Mermaid Killer Crosses His Tracks (Havfruemorderen krydser sine spor), Jørgen Nash publicly mocked and scorned the gender transition of his ex-spouse and former Situationist Peter Albert Lindell. Describing a meeting between the former couple in Malmö Kunsthal, Nash stresses how he first fell into a state of shock, then a fit of laughter, and lastly a furious state of mind where he desired “to murder this crazy person.” Paradoxically, Nash chooses to impose clear limits on the life-form of his former partner, while at the same time celebrating the “limitlessness” of his own artistic and sexual freedom, which in the memoir is visible when Nash brags about having sex with minors and their mothers at his and Lindell’s riding school.

Mikkel Bolt Rasmussen, Late Capitalist Fascism (Polity Press, 2021), 132.

Luc Boltanski and Eve Chiapello, The New Spirit of Capitalism, trans. Gregory Elliott (Verso, 2005).

François Cusset, La droitisation du monde (Textuel, 2016); McKenzie Wark, 50 Years of Recuperation of the Situationist International (Princeton Architectural Press, 2008).

J. V. Martin, “Antipolitical Activity,” Situationistisk Revolution, no. 1 (1962): 26, 27. This text is translated into English (which we are using here) in Cosmonauts of the Future, ed. Mikkel Bolt Rasmussen and Jakob Jakobsen (Neblua and Autonomedia, 2015).

“L’operation contre-situationniste dans divers pays” (author anonymous), Internationale Situationniste, no. 8 (1963): 24. Translation borrowed from →. Translator Kenn Knapp suggests that this text was written by Guy Debord.

“L’operation contre-situationniste,” 26.

Martin, “Antipolitical Activity,” 99–100.

Paraphrasing a later text by Thorsen, this strange Nashist nationalism or cultural organicism was of course “anti-nationalist,” but with its libertarian individualism, it was mostly “anti-internationalist” in effect. See Jens Jørgen Thorsen, “Draft Manifesto of Antinational Situationism,” in Cosmonauts of the Future.

For Asger Jorn’s writings on the ethnic and organic characteristics of Scandinavia, see The Natural Order (1962) and Things & Polis (1964).

“Kampen om det situkratiske samhället: Et situationistiskt manifest,” Drakabygget – Tidsskrift för konst mot atombomber, påvar och politiker, no. 2–3 (1962): 15.

“The Struggle of the Situcratic Society: A Situationist Manifesto,” in Cosmonauts of the Future, 92. The Swedish and English versions of the manifesto contain small differences.

Jørgen Nash, “Konstens Frihet,” Drakabygget, no. 2–3 (1962).

This term used by Nash and Jorn might very well derive from the writings of the racist anthropologist Leo Frobenius, who also figures in Jorn’s texts.

“L’operation contre-situationniste,” 24.

Lars Morell, Poesien breder sig: Jørgen Nash, Drakabygget & situationisterne (Det kongelige bibliotek, 1981), 79.

Slater, “Divided We Stand.”

Morell, Poesien breder sig, 85. Posing as journalists was a strategic camouflage often employed by Nashists to enter inaccessible sites, and was described by Nash as a method of the Fifth Column. This is also a general trick employed by Uwe Max Jensen and was used to get Ibi-Pippi into Museum Jorn in 2022.

Jens Jørgen Thorsen, Wilhelm Freddie: Brændende blade (Internationalt Forlag, 1982), unpaginated.

Madame Nielsen, “Er Kristian von Hornsleth og dermed ’provokunsten’ virkelig død – eller bare ligegyldig?” Dagbladet Information, July 27, 2020 →.

“L’operation contre-situationniste,” 26. Emphasis in original.

For more on this “interdisciplinary” dimension within the context of propaganda, see Jonas Staal, Propaganda Art in the 21st Century (MIT Press, 2019). On the notion of the “art industry” as complementary to the “culture industry,” see Peter Osborne, Anywhere or Not at All: Philosophy of Contemporary Art (Verso, 2013), 162–68. With the word “absolute,” we allude to Adorno’s briefly stressed idea of art as an “absolute commodity” in order to encompass the peculiar economic exceptionality of art. See Theodor W. Adorno, Aesthetic Theory, trans. by Robert Hullot-Kentor (Continuum 1997), 21; and Stewart Martin, “The Absolute Artwork Meets the Absolute Commodity,” Radical Philosophy, no. 146 (November–December 2007).

Mikkel Bolt Rasmussen, Den sidste avantgarde: Situationistisk Internationale hinsides kunst og cirkler (Politisk Revy, 2004).

Hito Steyerl, Duty Free Art (Verso, 2017), 181.

See Søren Schauser, “Tænk om Rasmus Paludan var et stunt,” Berlingske Tidende, May 6, 2019 →.

As literary scholar Jørn Erslev Andersen has recently argued, Asger Jorn explored the notions of situology and triolectics to conceptualize an aesthetic-epistemic process that never synthesizes (as in dialectical movement), but rather manifests as an open situation, in what he termed a “transformative morphology of the unique.” In contrast, the situology at play in neo-Nashist happenings is neither dialectical nor triolectical, but rather seems to follow a monolectic logic of subjugation and repulsion. This is a closed situation that is given in advance, an “isomorphology of the same.” For an in-depth account of Jorn’s situology, see Jørn Erslev Andersen, At sætte i situation: Asger Jorns triolektik & situlogi (Antipyrine, 2017).

For a report on Paludan’s appeal to schoolchildren, see Peter Thomsen, “Stram Kurs-leder er blevet et Youtube-fænomen blandt skolebørn,” Berlingske Tidende, September 19, 2018 →. Ultimately, Paludan’s political project in Denmark collapsed when he got caught in an online “sex chat” with underage boys on Discord. This marked the complete transition of neo-Nashism from an intriguing “child monster” to full-on demonolatry—a point of transgression that Paludan only affirmed when, three days after the revelations, he sought to stifle what he called “homophobic rumors” by announcing his marriage to a younger woman.

Staal, Propaganda Art in the 21st Century, 77.

This is reported in a catalogue text from the exhibition “Situationister 1957–71 Drakabygget,” held at the Skånska Konstmuseum in Lund, Sweden in 1971. The text can be read online at →.

In 2019, just a few months after the election, a survey showed that 28 percent of Danes agreed “strongly” or “somewhat” with this xenophobic statement continually expressed by Paludan: “Muslim immigrants should be sent out of the country.” See Jens Reiermann and Torben K. Andersen, “Hver fjerde dansker: Muslimer skal ud af Danmark,” Mandag Morgen, October 21, 2019 →.

See Mikkel Bolt Rasmussen, “On the Turn Towards Liberal State Racism in Denmark,” e-flux journal, no. 22 (January 2011) →.

Ana Teixera Pinto, “Illiberal Arts,” Paletten, November 4, 2020 →.

See Mark Antliff, Avant-Garde Fascism: The Mobilization of Myth, Art, and Culture in France, 1909–39 (Duke University Press, 2007).

Lene Myong og Michael Nebeling, “Racismens vold er modstandens kontekst,” Eftertrykket (originally published at peculiar.dk), April 22 2019 →; Pinto, “Iliberal Arts.”

Tellingly, the famous Swedish “hate speech” artist Dan Park made a symbol-laden election poster for Hard Line’s Uwe Max Jensen that included the phrase “freedom of art.”

On the relation between actionism and contemporary fascism, see Lütticken, “Who Makes the Nazis?”; and Lütticken, “The Power of the False,” Texte zur Kunst, no. 105 (March 2017) →.

Quoted in Mikkel Bolt Rasmussen, “To Act in Culture While Being Against All Culture: The Situationists and The ‘Destruction of the RSG-6,’” in Expect Anything, Fear Nothing, ed. M. B. Rasmussen and Jakob Jakobsen (Nebula and Autonomedia, 2011), 112.

Rasmussen, “To Act In Culture,” 96.

At Galerie Exi, Michèle Bernstein installed a series of model tableaux with titles from revolutionary defeats renamed as victories, e.g., Victoire de la Commune de Paris, Victoire des Républicains Espagnols, and Victoire de la Grande Jacquerie.