Notes

1

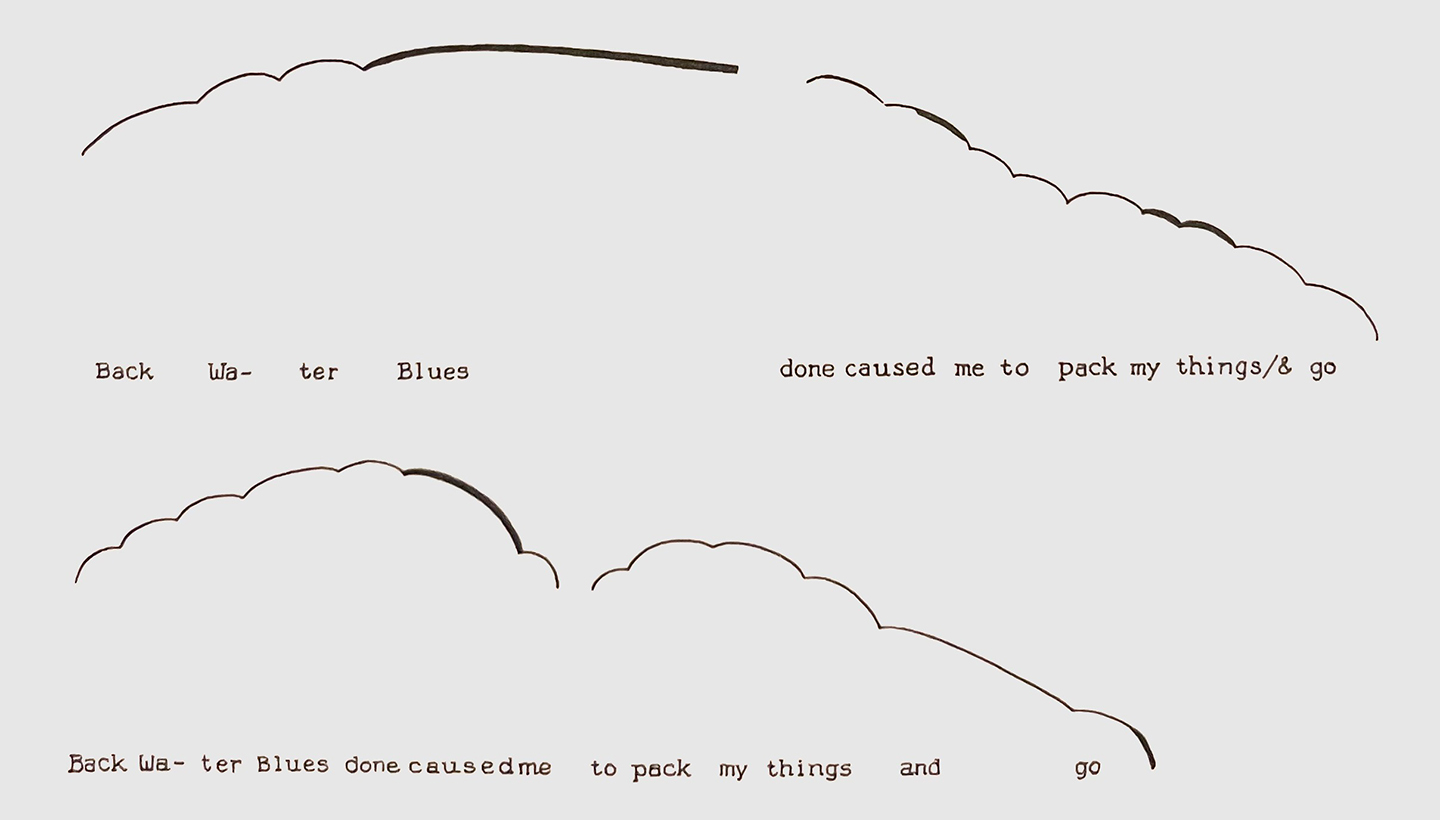

Alice Notley, Close to Me and Closer … (The Language of Heaven) and Desamere (O Books, 1995), 5.

2

The Descent of Alette (Penguin, 1992), 5.

3

Telling the Truth as It Comes Up: Selected Talks & Essays 1991–2018 (Song Cave, 2023), 131.

© 2024 e-flux and the author