After the term was more explicitly posed as a political tactic by French anarcho-syndicalists in the late 1890s (and formally declared at a Confederation General du Travail congress in 1897). See “Reading Between Enemy Lines” in my forthcoming book Inhuman Resources (Sternberg Press, 2025) for a brief sketch of the overall trajectory of sabotage as an idea.

Walker C. Smith, Sabotage: Its History, Philosophy & Function, 1913 pamphlet published by Industrial Workers of the World →. Fantasies of government oversight aside, this is by no means just in the past. Timothy Mitchell’s Carbon Democracy details this on the level of the planned restriction of the circulation of oil, while we can find extremely recent instances of a level of food destruction that easily belongs in New Earth. See for instance this report on food destruction during the Covid pandemic: David Yaffe-Bellany and Michael Corkery, “Dumped Milk, Smashed Eggs, Plowed Vegetables: Food Waste of the Pandemic,” New York Times, April 11, 2020 →.

Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, Sabotage: The Conscious Withdrawal of the Worker’s Industrial Efficiency (IWW Publishing Bureau, 1916), 5.

Louis Adamic, Dynamite: The Story of Class Violence in America (Viking Press, 1934), 373. Another account of adulteration can be found in Smith: “The doctor gives ‘bread-pills’ or other harmless concoctions in cases where the symptoms are puzzling. The builder uses poorer material than demanded in the specifications. The manufacturer adulterates foodstuffs and clothing. All these are for the purpose of gaining more profits.” Smith, Sabotage, 66.

Thorstein Veblen, The Engineers and the Price System (Batoche Books, 2001), 5.

His use of the term “handicap” here is worth noting given the concerns of this essay and the fact that it is in the early twentieth century that we see a shift in its meaning to refer increasingly to bodily impairment rather than adjusting the odds of a bet.

Veblen, The Engineers and the Price System, 55.

Veblen, The Engineers and the Price System, 5.

His attention to this dynamic is important, given that he was watching the shifts in the word’s meaning in real time, in the late 1910s and early 1920s.

I am here using “industry” as shorthand for sectors of waged work historically associated with “productive” and often masculine-coded labors of manufacturing, extraction, or the circulation of commodities.

Indeed, that strange unreadable/unprovable quality remains in such critiques almost solely as the sign of sneakiness and cowardice, of not fighting fair and out in the open. Of course, its advocates wouldn’t disagree that it does not come out into the open. Almost all early theorizations of sabotage make explicit how this ability to “strike on the job” and to tune the production/circulation process against itself, rather than coming out into public view or representational politics, is precisely the point and strength of sabotage.

James Boyle, The Minimum Wage and Syndicalism: An Independent Survey of the Two Latest Movements Affecting American Labor (Stewart & Kidd Company, 1913), 91.

Émile Pouget, Sabotage, trans. and introduced by Arturo Giovannitti (Charles H. Kerr and Company, 1912), 75.

Arturo Giovannitti, introduction to Pouget, Sabotage, 33.

We should also note how much the logic of sabotage has often been aligned with, and advocated by, those who refuse these sides, who refuse the naturalization and binarism of war that sends proletarians to murder each other under the sign of national necessity. Consider Joe Hill, for instance, the Wobbly songwriter and militant executed by the state on a false murder charge. Hill wrote of sabotage in a brilliant 1914 essay on “HOW TO MAKE WORK FOR THE UNEMPLOYED” (i.e., by “striking on the job” and slowing up production so as to make everything take longer and require more hours or more laborers). In that essay he writes, “This weapon is without expense to the working class and if intelligently and systematically used, it will not only reduce the profits of the exploiters, but also create more work for the wage earners.” But in an acerbic letter not two weeks before he was set to be killed, he also attacked the ground of national chauvinism and wrote that “war certainly shows up the capitalist system in the right light. Millions of men are employed at making ships and others are hired to sink them. Scientific management, eh, wot? As far as I can see, it doesn't make much difference which side wins, but I hope that one side will win, because a draw would only mean another war in a year or two.” That said, in a turn with a graveside humor only appropriate for his looming execution, and marked by a tone somewhere between sarcasm and deadly seriousness that characterizes many of his letters, he mocks those “silly priests and old maid sewing circles that are moaning about peace” and suggests instead that the “war is the finest training school for rebels in the world and for anti-militarists as well.” Joe Hill, “Letter from Utah State Prison,” September 9, 1915, in Rebel Voices: An IWW Anthology, ed. Joyce L. Kornbluh (PM Press and the Charles H. Kerr Library), 152.

See →.

Indeed, this is not an imaginative turn of phrase: it is an explicit part of the eminently weird tactics of British Special Executive Operations agents: “Dead rats filled with PE were prepared by taxidermists; they incorporated a Mk I11 oz guncotton primer, a short length of time fuse, and a No. 10 time pencil. The idea was that a dead rat left near a boiler or furnace might be shoveled into it for disposal. In that case no activation of the delay fusing was necessary, but it could also be activated and left where it would inflict damage.” Gordon Rottman, World War II Allied Sabotage Devices and Booby Traps (Bloomsbury, 2006), 52.

See my essay “Acid Doubt” at Triple Canopy for a longer articulation of this argument →.

As I examined earlier, one possibility of this is an increased capacity to recognize the kinds of links and circuits that were already in place and already organizing the world, even if the trope of breakdown/insight often too easily assumes that a critical or radical knowledge flows from this.

John Spargo, Syndicalism, Industrial Unionism and Socialism (B. W. Huebsch, 1913), 85. I would put Spargo’s reckoning with this in dialogue with another enemy of insurrection so to speak, Carl Schmitt, whose reading of class politics in The Crisis of Parliamentary Democracy also captures a crucial aspect of what I’d consider a collective and intentional self-inhumanization that has been anathema to more mainstream socialist or labor politics for much of the last century and a half. Schmitt writes that in the process of revolutionary organizing and a communist horizon, “the proletariat can only be defined as the social class that no longer participates in profit, that owns nothing, that knows no ties to family or fatherland, and so forth. The proletarian becomes the social nonentity. It must also be true that the proletarian, in contrast to the bourgeois, is nothing but a person. From this it follows with dialectic necessity that in the period of transition he can be nothing but a member of his class; that is, he must realize himself precisely in something that is the contradiction of humanity—in the class.” As for Spargo, for Schmitt this is a situation to be avoided. Carl Schmitt, The Crisis of Parliamentary Democracy (MIT Press, 1988), 62.

Spargo, Syndicalism, 94. And again: “What the Syndicalist has in mind is that the workers by becoming inactive, ‘motionless,’ destroy the entire structure of capitalism and create for themselves both the opportunity and the necessity for establishing a new social and industrial order” (91).

Crucial texts on this question include Joanna Hedva’s “Sick Woman Theory” (available online at →) and the reading of flexibility in Robert McRuer’s Crip Theory: Cultural Signs of Queerness and Disability (NYU Press, 2006), via Emily Martin’s work on neoliberalism.

See, for instance, Martin Sullivan’s “Subjected Bodies: Paraplegia, Rehabilitation, and the Politics of Movement” for not only a reckoning these forms of denigration, but also for his account of the production of a paraplegic subject position/subjectivity. In Foucault and the Government of Disability, ed. Shelley Tremain (University of Michigan Press, 2015).

In this way, these kinds of figurations can’t be reduced to a single kind of genre, as they are as common in horror as they are in supposedly feel-good stories of persistence.

See Amanda K. Booker, “Docile Bodies, Supercrips, and the Plays of Prosthetics,” in “Disability Studies in Feminist Bioethics,” special issue, International Journal of Feminist Approaches to Bioethics 3, no. 2 (Fall 2010); and Sami Schalk, “Reevaluating the Supercrip,” Journal of Literary & Cultural Disability Studies 10, no. 1 (2016).

This is a fact that produces genuine crises for people trying to get by, a sort of hinterland of never having enough and yet being trapped by the very mechanisms that allegedly support: the stipend is often too little, especially if more intensive regimes of care or medication are needed, and yet doing any waged work whatsoever disqualifies them from that support in full.

Marta Russel and Ravi Malhotra, “Capitalism and Disability,” Socialist Register, no. 38 (2002), 212.

I won’t pursue it here, but see my essay “Down to the Bone” in Inhuman Resources (forthcoming from Sternberg Press, 2024) for a discussion of the relation between psychoanalysis, PTSD, and “railway spine,” i.e., forms of often paralyzing injuries generated by the expansion of railway networks into urban areas. I also return to this in the final installment of this series, in terms of deaths and maiming caused by trains.

The framework that Jasbir K. Puar advanced around this is vital, especially in terms of thinking towards debility, rather than disability per se, as it attends to the violence done to people in ongoing and geopolitically normalized regimes of harm and debilitation that precisely elude becoming identifiable as disability. See Jasbir K. Puar, The Right to Maim: Debility, Capacity, Disability (Duke University Press, 2017).

Anson Rabinbach, “Social Knowledge and the Politics of Industrial Accidents,” chap. 3 in The Eclipse of the Utopias of Labor (Fordham University Press, 2018); Karin Bijsterveld, “Listening to Machines: Industrial Noise, Hearing Loss and the Cultural Memory of Sound,” The Sound Studies Reader, ed. Jonathan Sterne (Routledge, 2012); Michael K. Rosenow, Death and Dying in the Working Class, 1865–1920 (University of Illinois Press, 2015).

Mara Mills, “Deafening: Noise and the Engineering of Communication in the Telephone System,” Grey Room, no. 43 (Spring 2011).

Frank B. Gilbreth and L. M. Gilbreth, “Motion Study as an Industrial Opportunity,” Applied Motion Study: A Collection of Papers on the Efficient Method to Industrial Preparedness (Macmillan, 1919), 41.

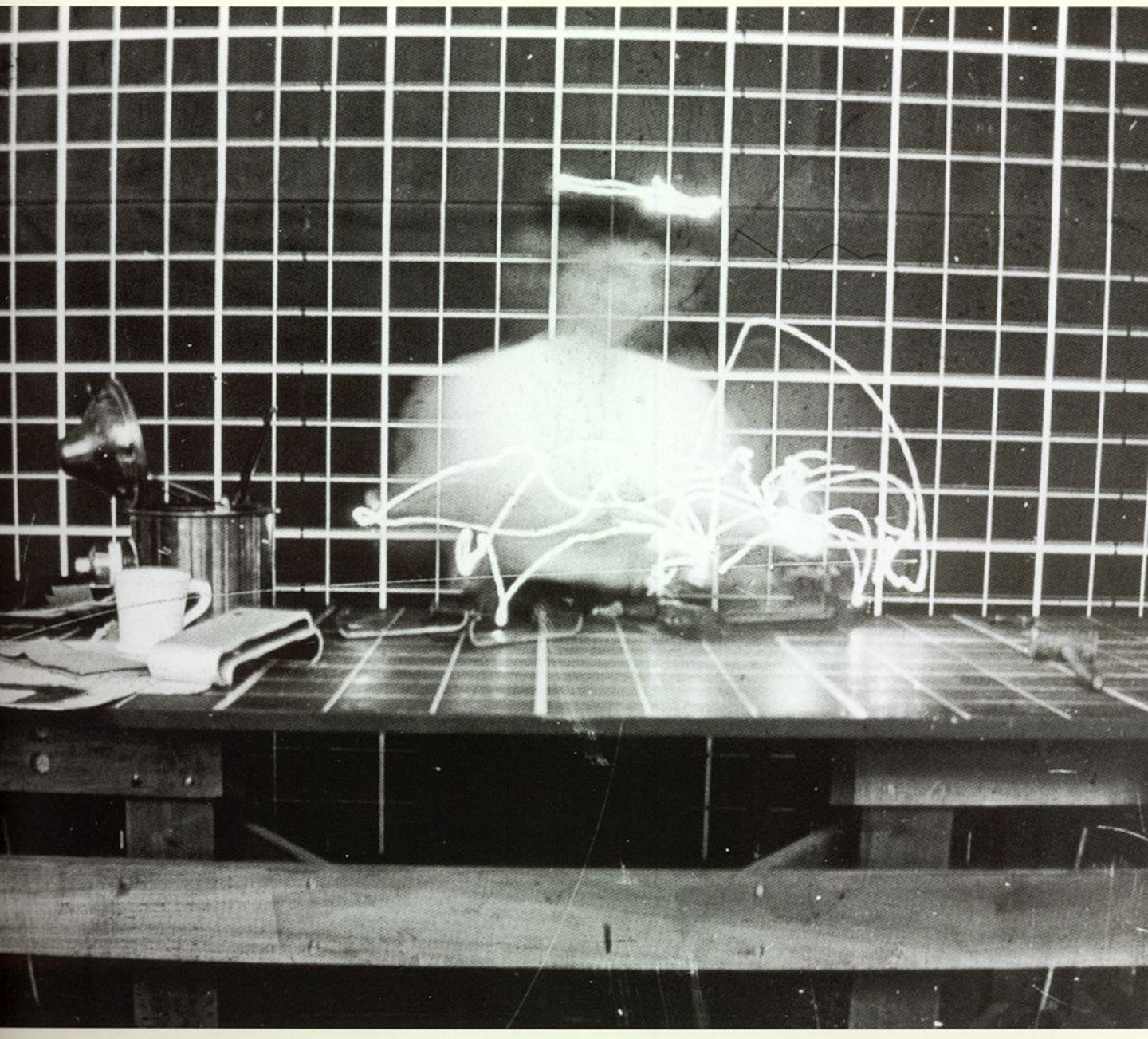

For more on their use of film, see Scott Curtis, “Images of Efficiency: The Films of Frank B. Gilbreth,” in Films that Work: Industrial Film and the Productivity of Media, ed. Patrick Vonderau and Vinzenz Hediger (Amsterdam University Press, 2009).

More specifically, they insist that the crux of the problem is those “crippled soldiers whose bent is towards some type of physical work,” “whose capabilities and inclinations are confined to physical work.” Gilbreth and Gilbreth, “The Crippled Soldier,” in Applied Motion Study, 134.

As with so much of their work, two tendencies run side by side, and occasionally are inseparable. On one side, there is the absolute centrality of productivity, efficiency, and the measurement of human worth under those terms alone. On the other, there’s a genuine commitment to trying to lessen fatigue, strain, and injury amongst those working, and, especially by Lillian in the wake of Frank’s death in 1924, to build spaces for domestic labor that could be not only efficient but also accessible. For instance, in 1948, Lillian Gilbreth was invited to design a kitchen for Howard Rusk’s Institute of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. In Bess Williamson’s excellent reading of Lillian’s history in this regard, she writes that, “rather than ‘elaborate prosthetic devices’ to adapt the worker to the environment, she wrote, buildings and equipment could be made accessible with ‘simple, inexpensive changes’ that would ‘work wonders.’ Gilbreth’s comments suggest the possibility of more widespread design change, but, like Rusk, she presented the task of producing this design change as a private and domestic one—something housewives could ask their husbands for help installing.” Bess Williamson, Accessible America: A History of Disability and Design (NYU Press, 2019), 54.

Versions of the phrase occur several times in their writing, and with a certain kind of general flattening that organizers like the Wobblies picked up on, albeit for revolutionary reasons. The Gilbreths write that “this country has been so rich in human and material resources, that it is only recently that the importance of waste elimination has come to be realised.” “Motion Study,” 41.

Gilbreth and Gilbreth, “Units, Methods, and Devices of Measurement Under Scientific Management,” in Applied Motion Study, 40.

“Grasp” and “Hold” use an inverted “U” to mimic either fingers or arms that, in “Hold,” now bear a straight line. The lower line of the “Search” eye becomes a bowl or vessel in “Transport Loaded,” then flipped over to “Release Load” and turned right side up again to show “Transport Empty,” waiting for its next cargo.

From Ralph M. Barnes, Work Methods Manual (John Wiley & Sons), 1944; quoted in Elliott Sturtevant, “‘Degrees of Freedom’: On Frank and Lilian Gilbreth’s Allocation of Movement,” Thresholds, no. 42 (2014): 161.

This table, credited to Lillian Gilbreth, is reproduced in Sturtevant, “‘Degrees,’” 165.

Even aside from the especially potent kind of neutralization that management strategies offer, sabotage is up against a broader mesh of ideologies and laws that resists this, politically and technically, putting the locus on the individual citizen and their mediated representation as the correct unit for political engagement.