This research is part of a collective project conducted by Red Conceptualismos del Sur (Southern Conceptualisms Network) about the transformations in ways of understanding and engaging in politics that took place in Latin America in the 1980s. The first phase of this project was recently presented at the exhibition “Losing the Human Form: A Seismic Image of the 1980s in Latin America” at the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía Madrid (October 2012–March 2013) and Museo de Arte de Lima (November 2013–February 2014). Part of this research was conducted in collaboration with the Peruvian researcher Emilio Tarazona between 2008 and 2011. Some of these materials will be presented for the first time in Peru at the exhibition “Sergio Zevallos in the Grupo Chaclacayo, 1982–1994,” curated by Miguel A. López at the Museo de Arte de Lima in November 2013.

The armed conflict in Peru ended in 2000 with the fall of the right-wing dictator Alberto Fujimori and his criminal and corrupt government. The principal actors in the war were the Shining Path Maoist organization (founded in a multiple split in the Communist Party of Peru), the “Guevarist” guerrilla group Túpac Amaru Revolutionary Movement (or MRTA), and the government of Peru. All of the armed actors in the war committed systematic human rights violations and killed civilians, making the conflict bloodier than any other war in Peruvian history since the European colonization of the country.

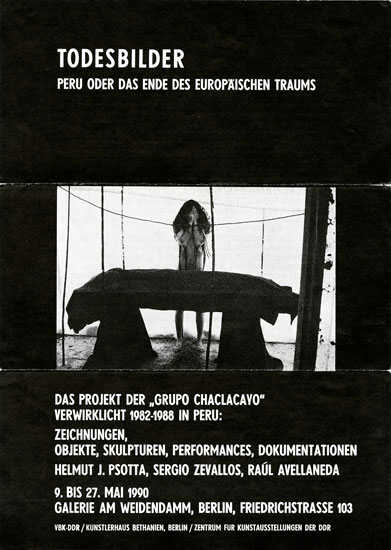

The show toured from 1989 to 1990 at the Institut für Auslandsbeziehungen (ifa) in Stuttgart, the Museum Bochum, the Badischer Kunstverein in Karlsruhe, and at the Künstlerhaus Bethanien in Berlin, among other venues. In addition, the group presented a series of live performances in Maxim Gorki Theater, Berlin, in May 1990. Their last presentation as a group was at Fest III (September 29–October 3, 1994) in Dresden, with the participation of, among others, the Yugoslavian/Slovenian band Laibach, the dance-theater company Betontanc, the filmmaker Lutz Dammbeck, and the artist and theoretician Peter Weibel.

On December 30, 1982, the government of Peru granted broad powers to the armed forces for “counter-subversive” campaigns in the parts of the central Andes deemed to be in a “state of emergency.” The human rights abuses that resulted were part of a deliberate strategy on the part of the military government. See Comisión de la Verdad y Reconciliación, Informe Final (Lima: CVR, 2003).

For a short history of Lima’s punk scene and “subte” movement, see Shane “Gang” Greene, “Notes on the Peruvian Underground: Part II,” Maximum Rocknroll 356 (January 2013). See also Carlos Torres Rotondo, Se acabó el show. 1985. El estallido del rock subterráneo (Lima: Editorial Mutante, 2012).

For a longer reflection about the radical artistic interventions and the underground scene in Peru in the 1980s, see Miguel A. López, “Discarded Knowledge: Peripheral Bodies and Clandestine Signals in the 1980s War in Peru,” in Ivana Bago, Antonia Majaca, and Vesna Vukovic (eds.), Removed from the Crowd: Unexpected Encounters (Zagreb: BLOK & DeLVe – Institute for Duration, Location and Variables, 2011), 102–41.

Luis Lama, “Pobre Goethe,” Caretas (December 3, 1984): 63.

“Crip” is a play on the word “cripple,” and its use here refers to the political resignification of disability and the questioning of how and why disability is constructed and naturalized. The “cripple” movement reclaims language and self-representation to direct them towards different modes of existence, confronting the dominant ideologies of “normalcy” and its medical lexicon. The movement also aligns itself with other bodies that have been pathologized, such as the homosexual. Crip activism and theory mobilizes the subversive potential of disabled bodies that refuse able-bodied norms, the productive demands of capitalism, and static identities. For the intersections of crip and queer, see Robert McRuer, Crip Theory: Cultural Signs of Queerness and Disability (New York: NYU Press, 2006).

Helmut J. Psotta (1937–2012) was born to a Jewish mother, Rosa Grosz, and a German father who was member of the Nazi Party. Psotta attended the Folkwang School in Essen, but found the school’s ideological tensions unbearable. Soon after he left the school, Psotta worked with metal designer Lili Schultz in her class at the Düsseldorf School of Arts, where Psotta met Joseph Beuys. At the age of twenty-three Psotta visited South America for the first time. He taught at the Institute of Design in the Architecture Department of the Catholic University of Santiago de Chile, and after seven years decided to visit Germany. Shortly thereafter, there was a military coup in Chile and his return to the country was no longer possible. Psotta moved to Gahlen, in Germany, where he created one of his major early series, entitled Pornografie—für Ulrike MM. He gave some lectures and seminars at the Rijksakademie van beeldende kunsten in Amsterdam, at the Jan van Eyck Academy and the Academy of Fine Arts in Maastricht, and at the Design Academy Eindhoven, among other schools. During these years his mother died and he decided to move to Utrecht, where he produced the series Konkrette-Poesie and the cycle of drawings entitled Sodom—für C. de Lautréamont. Despite various offers, he refused to make his work public, as he believed that only through anonymity could he be free as an artist. He eventually received an invitation to teach at the Art School of the Catholic University in Lima, where he lived between 1982 and early 1989.

Helmut Psotta, “Die Koloniale Jesusbraut Rosa von Lima und die Korruption der weißen Kaste order. Eine lyrische Version europäischer Brutalität…,” in Grupo Chaclacayo, Todesbilder. Peru oder Das Ende des europäischen Traums (Berlin: Alexander Verlag, 1989), 39–49. The beatification of Saint Rose of Lima in Rome in 1668, and her canonization by Pope Clement X in 1671, can be interpreted as a strategic gesture by the Church to consolidate its hierarchy and to symbolically proclaim the success of the processes of evangelization in the Americas.

Dorothee Hackenberg, “Dieser Brutälitat der Sanftheit. Interview mit Helmut J. Psotta, Raul Avellaneda, Sergio Zevallos von der Grupo Chaclacayo über ‘Todesbilder,’” TAZ (January 26, 1990), 22. In a 1921 text, Water Benjamin describes capitalism as a “religious phenomenon” whose development was decisively strengthened by Christianity: “Capitalism is purely cultic religion, without dogma. Capitalism itself developed parasitically on Christianity in the West—not in Calvinism alone, but also, as must be shown, in the remaining orthodox Christian movements—in such a way that, in the end, its history is essentially the history of its parasites, of capitalism.” Walter Benjamin, “Capitalism as Religion,” trans. Chad Kautzer, in Eduardo Mendieta (ed.), The Frankfurt School on Religion: Key Writings by the Major Thinkers (London: Routledge, 2005), 260.

For these images, the poet Frido Martin (Marco Antonio Young) performed as a queer Santa Rosa. Martin was one of driving forces behind the radical Peruvian poetry of the early 1980s, appearing with the Movimiento Kloaka and with the rock group Durazno Sangrando (consisting of Fernando Bryce and Rodrigo Quijano) in several public performances and poetry readings.

The “slaughter of the prisons” refers to the political repression that took place on June 18 and 19, 1986, following a riot by prisoners accused of terrorism in various prisons in Lima. The riot was started with the intent of capturing foreign media attention before the 18th Congress of the International Socialist (June 20–23, 1986), which was organized for the first time in Latin America. This slaughter was the greatest mass murder of the decade.

The speech of John Paul II in Ayacucho was delivered in the city airport, in February 1985, right next to Los Cabitos army headquarters, where a large number of peasants were brutalized and punished under suspicion of being “terrorists.” The inhabitants of Ayacucho had been denouncing these crimes since 1983, but they were ignored by the conservative archbishop Federico Richter Prada and by other local religious authorities who collaborated in the preparation of the papal speech. The Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (CVR) confirmed in 2003 that at least one hundred people were killed and illegally buried in Los Cabitos in those years. For a moving testimony by a Jesuit priest who confronted the subversive groups, military abuse, and right-wing religious authorities in Ayacucho during 1988 and 1991, see Carlos Flores Lizana, Diario de vida y muerte: Memorias para recuperar la humanidad (Cusco: Centro de Estudios Regionales Andinos Bartolomé de las Casas, 2004).

One of the founders of Liberation Theology was Peruvian theologian Gustavo Gutiérrez Merino, who coined the term “liberation theology” in 1971 and wrote the first book about this theological-political movement in 1973. See Gustavo Gutiérrez, A Theology of Liberation: History, Politics and Salvation (New York: Orbis Books, 1988).

Beatriz Preciado, “The Ocaña we deserve: Campceptualism, subordination and performative policies,” in Ocaña: 1973–1983: acciones, actuaciones, activismo (Barcelona: Institut de Cultura de l’Ajuntament de Barcelona, 2011), 421.

Action performed at the Sala Luis Miró Quesada Garland, in Lima, as part of the project eX²periencia curated by Jorge Villacorta in February 2013. For a broader consideration of Transvestite Museum of Peru see Giuseppe Campuzano, Museo Travesti del Perú (Lima: Institute of Development Studies, 2008); and Miguel A. López, “Reality can suck my dick, darling: The Museo Travesti del Perú and the histories we deserve,” Visible Workbook 2 (Graz: Kunsthaus Graz, 2013).

Renate Lorenz, Queer Art: A Freak Theory (Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag, 2012), 81.

Luis Lama, “Perversión y Complacencia,” Caretas (November 20, 1989): 74–76.

A preliminary version of this text was presented at the panel “Latin American Art as the Programmatic of the Political: The New Constructed Canon?” chaired by Claudia Calirman and Gabriela Rangel, during the XXX International Congress of the Latin America Studies Association (May 23–26, 2012) in San Francisco, California, and at the seminar “Campceptualisms of the South: Tropicamp, Performative Politics and Subalternity” organized by Beatriz Preciado at the Museu d’Art Contemporani de Barcelona - MACBA (November, 19–20, 2012).